In the first part we briefly examined some of the effect of universal credit on prices. Because of our long experience with inflation we assume prices will increase because they always have. This subtle bias carries forward, we generally expect social and political changes to result in higher prices.

Now prices are beginning to decline because of deleveraging which in turn diminishes support for higher goods prices including that of petroleum.

There are multiple, important, somewhat conflicting dynamics underway right now:

– Debtonomics: credit amplifying or triggering price changes.

– Debtonomics: the dollar/crude trade which determines the worth of both.

– Creeping dollar preference and amplified deflation.

– Debtonomics: ongoing collapse of the euro currency as a ‘going concern’.

– Bilateral international trade deals involving crude production that exclude the dollar.

Times change, it’s adapt or die! Here is Economic Undertow from just last January:

The five or six people who read this blog know there are two simultaneously operating economies in the US and world, the real economy of production and labor, resources and capital with an abstract and parasitic finance economy attached where the real cannot reach to remove it.The tapeworm economy is in the spasm of hyperinflation as credit is formed by finance firms with the moral hazard- encouragement of central banks and governments. Finance lends itself trillions so as to bid up assets and create a wealth ‘effect’ for itself. Ongoing real economy difficulties have so far not been allowed to spoil the wealth creation party. The tapeworm seeks to feed off the real economy more or less permanently rather than kill it outright.

The real economy is deflating, burdened by real costs for inputs alongside the excess debt service that the tapeworm economy refuses or is unable to lighten. The ‘container’ for both of these economies is a culture that holds out a (so- far false) material utopia of inevitable, endless progress. Advertising which is the lever of culture is a ‘diktat’: it is not just television or mobility that is demanded and promised but only acceptable types of flat screen televisions and SUV mobility.

Yes and no, that model is not quite correct. It doesn’t account for debtonomics.

We now understand that fuel by itself is worth more than the real-world enterprises that waste it regardless of what means are used to adjust the price. Enterprises earn nothing on their own and are essentially worthless. They exist solely to borrow, either on their own accounts, against those of their customers or against public accounts. Industrial enterprises produce credit as their primary product: other goods and services are intended to justify credit issuance in ever-increasing amounts. Part of this stream becomes the property of well-positioned ‘entrepreneurs’: enormous unearned borrowed profits are what drives the system. When debt = wealth, there is an incentive to take on as much debt as possible, keep what you can for yourself and to shift the burdens onto others.

Economies carry vast debts that cannot be retired or serviced by economies’ customers, system managers are wary of monetizing because the (debt) costs of doing so are even greater than the debts themselves.

Management is paralyzed by the internal contradictions of the debtonomy. We cannot get rid of (some of) the debt without getting rid of (all of) the wealth. We cannot get rid of the debt because we would need to take on even more ruinous debts immediately afterward. If we get rid of the debts the prices will fall leaving debt-tending establishments without capital. Our debts cannot be rationalized, the absence of debts cannot be tolerated. The debt system is rule-bound. Debts that were increased because of favorable rules face annihilation because of the same rules, changing the rules threatens debt elsewhere. Nowhere are there real returns to service the debts much less retire them. Nothing remains but the arm-waving of central bankers. If the banks create more debt against their own accounts, their efforts are felt at the gasoline pump which adversely effects debt service.

The debtonomy is Gresham’s Law applied (on purpose?) to goods and services; the bad drives out the good, the worst drives out everything else. The ‘bad’ enterprises which groan under massive obligations possess a competitive advantage over the virtuous ones that earn without taking any debts on. Debts are artificial earnings which are used to price the good companies out of business then engulf their markets. The final step is for the debt-gorged monstrosities to fall bankrupt due to their massive size, these are then bailed out by the even-more bankrupt sovereigns.

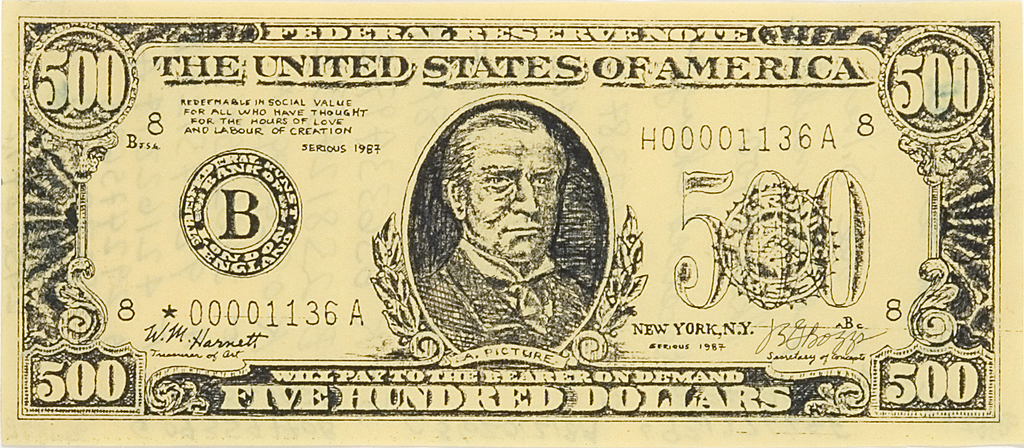

J. S. G. Boggs ‘Five Hundred Dollars’ (Pen and ink, click on for big.)

Obviously, if we don’t have debtonomics we will all wind up living in caves.

Chris Cook uses the term ‘Upper Bound’ to describe the fuel price level that constrains economic activity. The price rise can be caused by increases in the money supply or by a decrease in the amount of available fuel relative to the current money supply.

What happens at the other end of the bound? If the upper is tough to deal with the lower is good, right?

It goes without saying that the crude is vital. The ‘Business of debtonomy is debt’ but the presumption is of fuel waste for a ‘higher purpose’ which is embodied within our precious progress narrative. Without continuous waste debt becomes an unsupportable dead weight on all enterprises. Here is the confusion over the effects of fuel shortages on economies: ending waste is thrift, it is economical. Ending waste is fatal to debtonomy which needs the waste to justify its existence: economic thrift is an un-debtonomic catastrophe.

It is different this time: the decline of the fuel price means there is less fuel made available to waste, that the high cost variety is off the market. Low priced fuel means there are no businesses with credit. Lower price fuel is worth more than any enterprise that uses it, the lowest possible price means the industrial scale fuel waste enterprises are ruined, both producers and consumers.

So much for innovation.

The decrease in the dollar price of crude is ipso facto the market repricing more valuable dollars.’ The lower bound is where dollars become a proxy for crude and are hoarded. At that point all things are discounted to the dollar because the dollar traded for crude is more favorable than a trade of anything else for crude, that includes dollar-denominated credit.

Just like the upper bound where a dollar is worth less with each increase in fuel price, the lower bound represents a dollar that is worth more because of its price in crude. A low crude price has a dollar that is worth too much to be used for carry trades or interest rate arbitrage which is the primary business activity within the debtonomy.

The lower bound is reached when currencies are discounted to dollars. A reason for this is the universality of the dollar. Because the US has been for so long the world’s consumer of last resort, goods that were sold for dollars in the US are tradeable elsewhere for the same dollars. The dollar purchases of the past and dollars in circulation now are the purchasing power of the future.

The dollar is also the world’s reserve currency, dollars settle trade accounts. The trade of goods between countries whose currencies are illiquid may have foreign exchange risks that exceed the worth of the goods trade. The exchange of the currencies for dollars bypasses the risks because the universal dollar is a liquid substitute for third-party currencies. Reserve status of the dollar and its universality provide leverage that other currencies do not possess.

The trade of dollars for crude sets the worth of the dollars rather than do the central bank(s), this trade takes place millions of time a day at gasoline stations all over the world.

Motorists determine the worth of money, central banks are irrelevant. In their futile attempts to assert some sort of relevance the central bankers and policy makers set money rates to zero, they ignore moral hazard and bail out their clients. They seek to reduce the worth of money relative to other money. In doing so the bank surrenders what small fragments of policy-making ability which remain to it. Bankers can set interest rates to zero but no further, can whitewash the accumulation of risk but cannot set the money worth of petroleum except to make it unaffordable which precipitates the catastrophe the bankers are desperate to prevent.

The catastrophe the bankers are desperate to prevent is the destruction of demand, where fuel falls into strong hands and dollars are hoarded because they are proxies for scarce petroleum, energy in-hand.

Because of the widespread propaganda that crude is plentiful there is little incentive to ‘reserve’ it by gaining and hoarding dollars. People believe in inflation and the magic of central bankers. As the perception of fuel scarcity takes hold access to fuel is gained by way of holding currency. The scarcity of funds lowers the fuel price, increasing currency worth which in turn provides even greater incentive to hoard it.

Extreme revaluation is preference for the dollar above other currencies including those of producer countries. The dollar holders buy fuel by purchasing fuel producers’ currencies in foreign exchange markets. if currencies are swept from F/X markets the discount against the dollar is taken in producers’ home markets. This particular dynamic may not be underway in Iran but the discounting rials for dollars is.

Extreme revaluation is preference over producer currencies: consumer goods are available for sale in dollars rather than in the local currencies. Consequently, dollars are bid for strongly in native currencies as is underway in Iran.

Inflation in non-dollar currencies is a consequence of dollar preference. Producers reject third-party currencies that do not trade in international currency markets or are volatile or illiquid. The freely-traded dollar is always available, the fuel purchaser trades his currency at a rapidly expanding discount to dollars.

The third-party euro is not in short supply within the reserve accounts of the European Central Bank! Mario Draghi doesn’t buy fuel with the spare change, those who would buy fuel with the euros have no access to them. The market shrinks along with the ability to pay, the result is strikes by truck drivers in Greece and Italy: conservation by currency means.

A preference is for cash over credit because the cost of credit even with negative real interest rates is greater than the cost of holding cash: this is deflation.

Dollars are preferred over euros if for no other reason than the questions about whether there will be a euro.

Dollar preference also takes hold when fuel subsidies in local currency are eliminated, the price of fuel in dollars is a better deal for consumers than in local currency. As monetary authorities react the result is more local currency in circulation and hyperinflation. Remember, inflation is always a currency arbitrage, to sell the currency you are stuck with to gain the currency you need.

Dollar preference is when a local currency vanishes from circulation such as the euro in Greece. A dollar black market will give the Greeks cheap fuel and penniless Greeks or hyperinflated fuel prices that Greeks cannot afford fuel with inflated wages. Here is the arbitrage again: either the drachma against the euro or drachma against the dollar.

Dollar preference effects net energy which is consumption taking place in energy producing countries. This consumption is entirely dependent upon consumer goods that are affordable because of high fuel prices. Iranians produce automobiles and other Iranians buy them because the national oil company is able to sell its product for $110 per barrel. The price subsidizes both Iran’s debts and her energy waste. Ditto for the energy consumption of Saudi Arabia, Russia, Kuwait, Iraq and all the rest. When energy prices fall so will energy consumption in producer countries if only because lower priced oil production will be too scarce to waste.

At $10 per barrel, Iran will produce very little fuel, only from the cheapest and easiest to produce fields and will trade it for hard currency only. Domestic sales will take place in black markets for dollars or gold, few Iranians will have dollars and those that do will hold onto them for emergencies. Hard currency earned by the export of crude will be used to buy food and medicine, not luxury automobiles and television sets.

Diminishing net exports depends on high prices which are in turn dependent upon constantly expanding credit. When cash is preferred over credit there is nothing to support the high prices or fuel waste. Cash is hoarded and credit is evaporated.

The end-game of dollar preference is crude-driven dollar deflation as took place in the US in 1933. Dollars were held as ‘gold in hand’ and business in the country was the buying and selling of currency to obtain gold. The deflationary impulse was ended when the world’s governments ended specie and fixed convertibility, cutting the currency links to gold. The need will be for the US to end the dollar’s convertibility to crude, to go ‘off crude’ as countries went ‘off gold’. The alternative is for dollars to vanish from circulation and cease to be a medium of exchange. Local currencies emerging in the dollar’s place will be of little use in the obtain of fuel imports, the country will be limited to the petroleum that can be sustainably produced on its own soil.

Dollar preference is self-limiting. Dollar preference in 2012 is the demise of the euro, its unraveling illuminates euro mismanagement. Doubts about currency regimes take root. The differences between the euro, yen, sterling, yuan and dollar currencies are minuscule. Euro debts are no different from the debts of the others, European waste is no different from the waste of others. There is nothing special about the dollar other than a military machine that is debt-dependent and failure-prone. Dollar preference condemns the euro which starts the clock on the ultimate death of the dollar.