Industry and its necessary expansion is dependent upon a constant increase of available fossil fuel. Factories, houses, offices and stores burn fuel in their furnaces. Mechanized agriculture, which feeds most of us, requires fuel for its machinery as well as chemicals and fertilizers using- or derived from petroleum. Fuel- or fuel products are part of every aspect of daily life. Every form of industry from mining to packaging of finished goods is dependent upon liquid fuels as are automobiles, trains, trucks, aircraft and ocean-going goods-transport vessels. Our buildings are made from steel, composites, concrete, chemicals, all are goods made from- or with petroleum, natural gas or coal feedstocks. Our roads and our roofs are made of asphalt. Nuclear, solar, wind and hydropower are petroleum-fuel dependencies. Industrialization runs on fossil fuel energy, without fuel in continually increasing quantities there is no ‘economic growth’.

The ongoing failure of the world’s economies is the matter of insufficient increase in the amount of available fuel: this failure feeds back into various economic sub-systems, mainly those that generate and resolve credit.

Credit is a proxy for goods to be gained- or offered in the future. If there is less fuel in the future, credit is undermined as there is no point to it: goods or customers will be unavailable. We all live in- and make use of a physical, dimension-constrained world that ‘has or has not’. Managers can pretend otherwise but markets price reality: right now markets are pricing fuel scarcity.

Enter The Double Whammy.

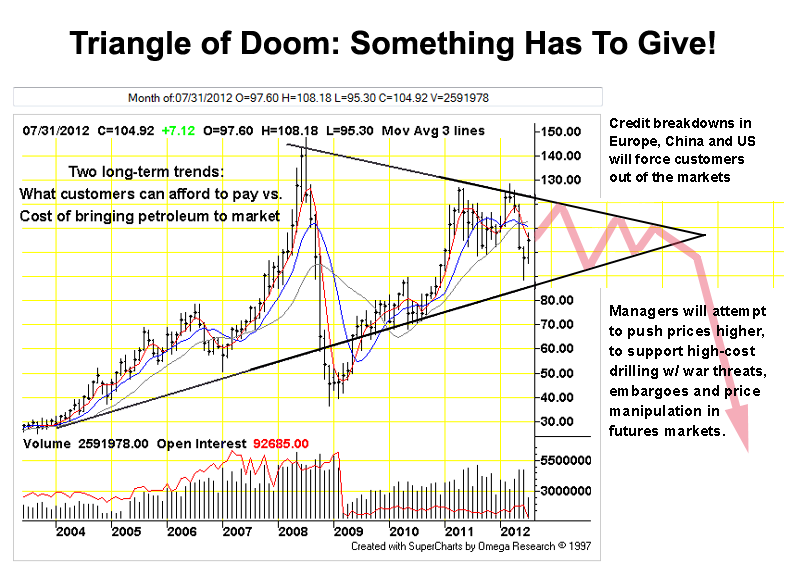

Figure 1: The economic dilemma in one chart, by TFC Charts (click on for big): new fuel to replace the trillion barrels already wasted is increasingly costly. At the same time the economy cannot borrow enough to afford this more expensive fuel.

The economy needs to grow to meet high fuel prices, it cannot grow because of high fuel prices.

Analysts insist cost is unrelated to the ability to meet the cost: this is wishful thinking. The higher cost of credit effects the ability of buyers to bid for fuel because they must calculate the combined cost of fuel and the necessary credit.

High-priced fuel is no more productive than low-priced variety: $20 fuel buys same output of goods and services as does $120 fuel. The pricey fuel isn’t better, it simply costs more … as does the credit needed to meet the higher fuel cost. Firms are clobbered by the combined costs and so are their customers.

Managers seek to adjust by reducing administrative interest rates but the deflationary impact of high fuel prices represent another double whammy. Money itself is too cheap: represented by too-high prices for fuel. At the same time, money is too pricey: represented by the proxy relationship between fuel and money reinforced millions of times per day at gasoline stations around the world. Pricey money is fuel, some monies are more fuel-like than others. Money-fuel is hoarded, credit evaporates: the outcome is worldwide currency shortages, dollar preference and job shedding.

‘Inflationary’ paper promises are worth more than human labor because promises can be converted to fossil fuel labor. Little imagination is needed to see how this fossil fuel endgame plays out: extremely scarce currency, no credit, scarce fuel and little remunerative work. The machines will unfairly compete with humans … as long as there is some fossil fuel production somewhere, industrial jobs will shrink- then vanish.

Meanwhile, borrowing is becoming unaffordable: debt is expensive in nominal terms (in the euro-zone) and in real terms (in Japan). Debts are taken on to buy fuel and fuel wasting machines, more debts are taken on to buy the second rounds of fuel and machines and to retire the first rounds of loans. The process is repeated and loans pyramid. When the costs become breaking both lenders and borrowers fail. The outcome is diminished availability of credit, less ability to pay.

At some point this ability to pay falls below the level needed to bring new fuels to the users, there are shortages.

If all else remains the same, the ‘too-costly fuel period’ will occur within five years: it is not likely that all else will remain the same. A breakdown in finance such as banking collapse in the Eurozone will accelerate the process. Right now the cost to produce new petroleum at the well head or at the bitumen pit is very close to the low prices that the market is willing/able to offer. As credit vanishes and prices decline, these expensive-to-produce fuels are shut-in as unaffordable.

After high-cost fuel is off the market what remains is the dregs of the low-cost fuels. The price regime does not work backwards. If $60- or $50 per barrel oil is unavailable there is little- or no $40 or $30 oil to lift. The ‘easy oil’ has already been squandered, ditto with ‘easy’ natural gas, coal, gold and uranium (water). Many analysts believe that oil prices are ‘fixed’ to the current high level by speculators: that prices will decline to historic levels once speculators are cleared from the markets. This is incorrect, when expensive fuels become unaffordable what remains will be hoarded.

Credit diminishes as consumption becomes useless as collateral. Shortage of good collateral is a reason the economy cannot borrow enough now. The worth of fuel-waste enterprises diminishes with time. Not only does industrialization destroy its own supply of capital, it is necessary for industry to take on more debt in order for it to do so. What matters is not the location of capital destruction or the details of the process rather it is the fact of it.

– Petroleum fuel waste is uniformly automobile use which does not provide any economic return: driving the car does not pay for either the car or the fuel burned in it. The beneficiary of car use is the car maker and seller, the road builder, the house-builder/developer who creates the car habitat, and the fuel supplier. The car is simply the instrument by which these enterprises borrow their returns: this is at the expense of the rest of the economy and future generations who must retire the associated debts. Hundreds of trillions of obligations have been taken on already, meanwhile future generations are presumed to waste their ‘own’ fuels while taking their ‘own’ immense debts. How this is supposed to work out is never explained.

– Geology versus policy: fuel price increases reflect increasing difficulty to recover fuel rather than increase of ‘money’ which is the increase of (scarcely- serviceable) debt.

– Efficiency Relativism: system efficiency gains are overcome by demand growth: automobiles are easier to manufacture than oil deposits are to find then exploit.

Fuel prices are expected to increase as a market response to supply constraints and have done so since 1999. Those with insufficient credit are excluded from the market, fuel is rationed indirectly. Conventional analysis extrapolates increased credit in wholesale markets leading to galloping prices without limit: $200 – $500 per barrel of oil. This sort of price activity cannot take place:

– Price rationing either works or it doesn’t. Price rationing works when prices are seen to decline.

– Within market trends both the highest- and the lowest prices decline over time. Since 2008 the highest price has declined from $147 per barrel to $128. The highest price in the upcoming year is likely to be less than $120. This has little to do with fuel availability rather the ability of finance to produce credit and customers to afford it.

– The price that constrains consumption tends to be much lower than economists assume.

– As institutions/firms fail, credit diminishes.

– ‘Artificial failure’ as debtors refuse to borrow as to do so means certain ruin. This diminution of credit in retail markets cannot support high wholesale prices. Believe it or not, some already conserve energy voluntarily!

– Crude prices are caught in a contest between asset price in wholesale market versus the ‘street price’: what a refiner can earn by the sale of his products in excess of what he pays in the wholesale market. When demand declines the price to be paid also declines. Debtor bargaining power increases so that sector demand is moderated. Markets are not one-way: sellers are not price setters at all times or places. If buyers cannot pay or refuse to do so, the seller loses his money. The seller cannot do so continually without his own failure.

Prices periodically rise to unaffordable levels then decline. The high prices set during these intervals themselves diminish over time. These declines occur as the ability or willingness of fuel users to borrow diminishes. In real terms the cost of fuel increases relative to other costs, nominal prices decline.

At some point the real costs are too high to allow at-scale industrial use. Demand diminishes for petroleum because there are fewer industries to make use of it. Entire ‘waste-based’ economies fail. Industrial workers are cast into general unemployment, the industrial wealth of the world is extinguished by deleveraging: little remains of industry in the ‘modern’ sense for wealth to be a claim against.

This endgame is underway right now in parts of Europe. The process cannot be undone, outmaneuvered or negotiated with. Given time, the leaky bucket becomes the empty one: ‘Conservation by Other Means’ (to paraphrase Clausewitz).

Figure 1 above illustrates the industrial world’s cognitive dissonance. We pretend the world’s non-renewable resource base is inexhaustible when increased production cost is evidence to the contrary. We drain resources faster while insisting the exhaustion process has no ongoing effects, that waste has no consequences, that what sets the price of a good is independent of what enables the customer to meet that price.

Industry insists there are two separate economies that exist in parallel: one economy functions perfectly while the resources available to its twin are unavailable.

In this real world, when one economic factor is constrained the effects are felt everywhere albeit unequally. China becomes the beneficiary of Europe’s economic destruction: the Chinese consume what the Europeans cannot.

The Europeans cannot consume because their credit-worthiness is shifted to the Chinese. The same is true of the Americans. (from Stuart Staniford, Early Warning)

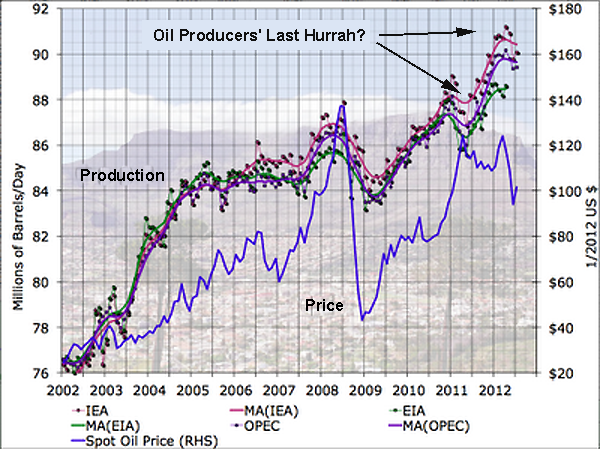

Figure 2: The increase in crude price has brought new supply to market: at what cost and for how long?

As the supply of credit diminishes, the financial support for development of new reserves will also falter. Diminishing credit effects the willingness of customers to bid and their ability to take deliveries. Credit has been the support for all industrial activities, nothing lasts forever.

Here is Michael Klare, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE):

… with production already declining sharply at most of the world’s major existing oil fields, more and more of the oil will come from harder-to-get-at sources—ultradeep-water deposits, Arctic reserves, the oil sands of Canada’s Alberta province, and the extraheavy crude of Venezuela’s Orinoco Belt. If exploited to the fullest potential, Venezuela’s reserves alone could satisfy world demand for another generation. But that oil will not be brought to the surface with the oil rigs we saw in the film There Will Be Blood (2007), notes Klare. The new technology will be more sophisticated, more resource demanding, more environmentally threatening, and of course, much more expensive.

None of this matters when we cannot afford it.