But by her still halting course and winding, woeful way, you plainly saw that this ship that so wept with spray still remained without comfort. She was Rachel, weeping for her children, because they were not.— Melville

It was just a matter of time, (NY Times):

American Is Killed in First Casualty for U.S. Forces in Syria CombatBEIRUT, Lebanon — The United States military suffered its first combat death in Syria on Thursday when a service member was killed in the northern part of the country, an area where the Americans are helping to organize an offensive against the Islamic State.

… a matter of time, (Washington Post):

First U.S. service member killed in Syria was a bomb disposal technicianThomas Gibbons-Neff

A U.S. Navy bomb disposal technician was killed by an improvised explosive device in northern Syria on Thursday, the Pentagon announced in a statement.

Senior Chief Petty Officer Scott C. Dayton, 42, of Woodbridge, Va., was killed near Ain Issa, a town roughly 35 miles northwest of the Islamic State’s self-proclaimed capital of Raqqa. The death marks the first time a U.S. service member has been killed in the country since a contingent of Special Operations forces was deployed there in October 2015 to go after the extremist group.

Dayton was assigned to Explosive Ordnance Disposal Mobile Unit 2 based in Virginia Beach and was also a qualified surface warfare specialist. While Dayton was the first American to die fighting against the Islamic State in Syria, he is the fifth U.S. service member killed in combat since the U.S.-led campaign to rid the region of the Islamic State began in 2014. Last month, Chief Petty Officer Jason Finan, 34, was killed outside Mosul in northern Iraq. Finan was also a bomb disposal technician and had been working with a team of Navy SEALs when he was killed.

The first American soldier to die in Vietnam (La Colonie de Cochinchine to the French) was Lieutenant Colonel A. Peter Dewey of Chicago, who was shot to death on September 26, 1945, a few weeks after the Japanese surrender. Dewey was on his way out of the country when he and his companion Maj. Peter Bluechel failed to stop at a Viet Minh checkpoint near Tan Son Nhut airfield outside of Saigon. Dewey was attached to the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) the predecessor to the Central Intelligence Agency. He and his team of four was tasked with locating and releasing American POWs as well as monitoring Anglo-French efforts to regain control over what was once ‘French Indochina’ from the defeated Japanese. He wound up in a heated disagreement with the British commander Gen. Douglas Gracey over the political status of the locals and was ordered to leave the country.

Approaching the checkpoint the Vietnamese called out; Dewey answered in French while attempting to drive around the obstacles; the Viet Minh mistook him for a Frenchman and opened fire. Dewey was shot in the head and killed instantly, his jeep left the road and rolled over into a ditch. Major Bluechel was miraculously unhurt. He was able to extricate himself from the checkpoint under fire and make his way across the adjacent Saigon Golf Course to the OSS headquarters, the Villa Ferrier. Here, an American captain, a couple of journalists and four others were having lunch. Warned by Bluechel, the Americans armed themselves and fought a pitched battle with the Viet Minh that lasted for several hours. Eventually, the attackers withdrew, leaving behind several dead. Lt. Col. Dewey’s body was never recovered, it turns out his Jeep was stolen and the body was taken away by the Vietnamese and thrown into a river; he became the first American Missing In Action in what would become one of the longest and in many ways the most costly war in American history.

The first American soldier to die in Korea was a nameless infantryman who was killed June 5, 1950. The soldier was a member of the 400- man Task Force Smith; a component of the US 21st Infantry Regiment of the 24th Infantry Division, sent from Japan to prevent North Korean forces from overrunning the South. Their mission was to fly into South Korea, close up with the enemy and hold them off long enough for reinforcements to arrive by ship. The task force headed north from their debarkation airfield to a position near the town of Osan, a few miles south of Seoul. There, the soldiers dug in along the tops of two small hills overlooking the road south.

Americans rushed into Korea like those in the 21st Regiment were peace-time garrison troops, inexperienced and poorly equipped. They lacked heavy weapons needed to knock out the North Koreans’ Soviet-made tanks. The task force fielded an artillery battery of six 105mm guns with a twelve-hundred rounds of conventional high explosives but only a half dozen HEAT anti-armor rounds. They also had six obsolete bazookas, a half-dozen mortars, a couple of recoilless rifles and six heavy machine guns. Individual soldiers received a wing-and a prayer: 120 rounds of rifle ammunition and two days’ rations each.

When the North Korean tanks motored into view a little over a mile from the American positions, the artillery opened fire with their high explosive shells; these had little effect on the armor. As the leading group of eight tanks rumbled across the US lines, the single artillery piece firing the hollow-charge rounds was able to disable two of them, setting one on fire. During the melee that followed, a North Korean tank crewman shot and killed the American soldier with a submachine gun as the Korean tried to escape from his burning vehicle.

The Americans were then approached by another twenty-five tanks, these passed through the lines undisturbed: bazooka- and recoilless rifle rounds from point blank range either failed to explode or bounced off. The tanks were followed a short time later by a set piece assault on the task force’s flanks by 5,000 North Koreans supported by more tanks, mortars and artillery. After expending their ammunition into the surging North Koreans, the task force commander Col. Charles Bradford Smith ordered a withdrawal under fire. Because of poor preparation and breakdowns of communication, the uncoordinated maneuver quickly turned into a rout. Small groups of surrounded soldiers, much of the Americans’ equipment and many wounded were left behind, also the bodies of dead Americans, some who had been executed by the North Koreans. The first US fatality in South Korea was an unknown soldier, another MIA.

The first American soldier to die in Iraq was Navy pilot Lieutenant Commander Michael Scott Speicher whose FA-18 fighter jet was shot down over western Iraq, January 17, 1991, a few hours into Operation Desert Storm. What Speicher’s mission was during that day or why he was flying over western Iraq as the war was unfolding in the east is not known nor was his ultimate fate. What is known is that Speicher’s aircraft was hit during a dogfight with Iraqi jets and that he was able to eject. In 1994 pieces of the wreckage were recovered by a Qatari officer on a hunting trip, the site was then examined by satellite. While the Pentagon mulled over the different ways to retrieve Speicher’s remains or to make a determination if he was still alive, the Saddam government combed the crash area removing whatever parts of the aircraft were left. In 2009, Speicher’s remains were recovered in Anbar Province and positively identified. Speicher is buried in Jacksonville, Florida.

The promise the Vietnamese made was to free itself from external rule, a promise that required 30 years and millions of Vietnamese casualties to keep.

The first American soldier to die in World War Two was Army Air Force Captain Robert A. Losey who was killed by a German bomb during an air raid in Dombas, Norway, on April, 21, 1940; part of Hitler’s campaign of conquest in Scandinavia. Losey, 32, a meteorologist by training, was the new American Assistant Defense Attaché to the US diplomatic mission in Oslo, having arrived in February, only a few weeks before the invasion. He, and the American Minister, Florence Jaffray Harriman, were working to evacuate American diplomats and their families as well as Norwegian government officials to neutral Sweden when the Dombas rail yards were attacked from the air. Losey was just inside a railway tunnel observing the aircraft when a German bomb struck the entrance, sending a splinter through his heart; also killed were five Norwegians taking shelter nearby.

Losey’s remains were recovered and delivered back to the US along with a letter of regret from the German Luftwaffe commander Hermann Göring to USAAF commander Maj. General Henry ‘Hap’ Arnold. Losey is buried at West Point.

The first American soldier to die in Afghanistan was CIA commando Capt. Johnny Micheal Spann, who was killed November 25th, 2001. Spann was overwhelmed by Taliban militants being held at the Qali-Jangi fortress near to Mazar-e Sharif; in northern Afghanistan during the opening phase of the US Afghan invasion. The prisoners had been herded into the fortress after pretending to give themselves up, many were armed with concealed grenades and side arms. Their aim was to gain control of a large cache of weapons that had been stored in the compound earlier by the Taliban. During an interrogation conducted by Spann in the fortress’ courtyard, a number of the militants rushed him, his associate David Tyson and the Afghan guards. Spann shot several with his personal weapon before being knocked down and beaten, in the chaos that followed he was shot in the head and killed, either by a friendly fire or from a weapon concealed in the clothes of a militant.

The initial skirmish turned into a siege as the 490 militants took over the arsenal then held off US special forces, British commandos and Afghan Northern Alliance forces for over a week. Air strikes and armor reduced the militants’ numbers, as the Alliance forces bored in, surviving militants made a stand in a fortified cellar in a corner of the compound. There they withstood satchel charges and grenades, burning fuel and smoke. They laid down their arms only after the cellar was flooded with freezing water from a nearby irrigation canal.

Spann’s body was returned to the US and buried in Arlington Cemetery.

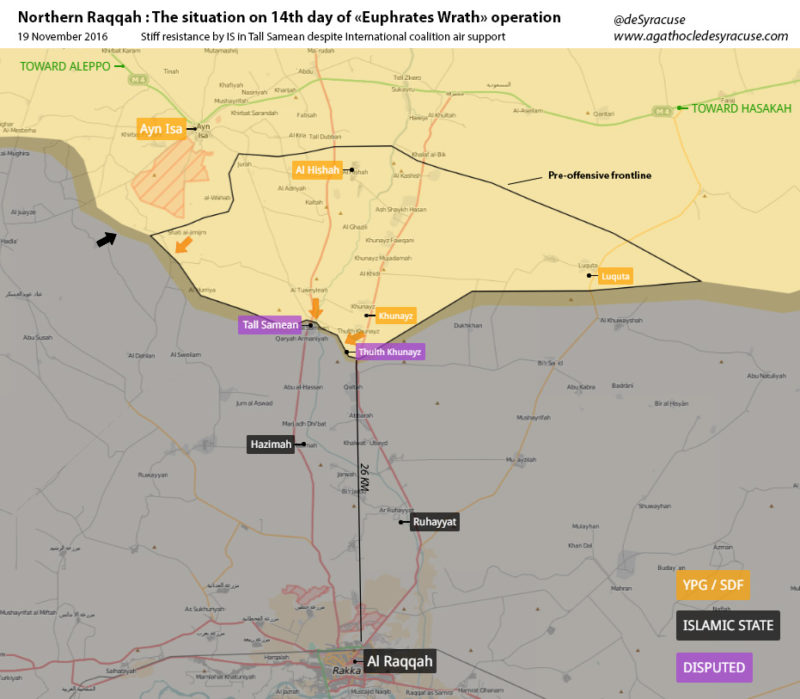

The Kurdish offensive against the Islamic State ‘capital’ of Raqqa, Syria; (Map by Agathocle de Syracuse). In a very short time with minimal resources, the Kurds of northern Syria have created a formidable political and military organization. It is reasonable to think the Kurds will link its areas of control across northern Syria together and clear Raqqa in a few months. The wildcard is Turkish interference; if they meddle the operation will take longer, perhaps months or years.

The situation in southeast Asia at the end of World War Two was confused and chaotic. Effective Japanese resistance across the empire was ended August 10 after the second atomic attack on Nagasaki. Japanese forces in Indochina surrendered to local authorities on August, 15; yet these authorities were themselves Japanese puppets. The Imperial soldiery, who might have been expected by the Allies to maintain order chose to remain in their barracks. In Hanoi, Viet Minh cadres responded to the security vacuum by taking over government offices. On the 26th, Ho Chi Minh arrived followed by an OSS ‘Deer Team’ that included Major Archimedes Patti. The team had parachuted into Tonkin, the northern part of Indochina earlier in March, 1945, to obtain intelligence and train Ho’s minuscule guerilla band. After the surrender, the OSS team was ordered to Hanoi to assist in locating and repatriating Allied POWs held by the Japanese in the north.

In Hanoi, Patti stood on a platform next to one-time history teacher, Vo Nguyen Giap and watched as the Vietnamese celebrated the end of Japanese occupation and the creation of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. To the ecstatic crowd, Ho Chi Minh read the Vietnamese Declaration of Independence, modeled after the American version, one that Patti himself helped to write.

Colonel Dewey and his OSS ‘Team 404’ arrived in Saigon on September 4th, following another OSS detachment as part of Operation Embankment. Dewey’s first act was to gain the release of 214 American internees held in two separate Japanese POW camps in Saigon. These men were put on a fleet of DC3s and flown out of the country the following day.

At the Potsdam Conference in August, the Great Powers Russia, America and Britain agreed the Japanese surrender in all of Indochina would be taken by the Chinese Nationalist (Chiang Kai-Shek) army north of the 16th parallel and the British would accept the Japanese surrender in the south. The British were the first to arrive: a Gurkha division from Burma (about 15,000 men) along with a small detachment of French paratroopers shipped into port on September 12th. With the arrival of the British, Dewey’s official duties were ended, but his OSS superiors had not yet decided what to do with him. Dewey made use of the time to motor around Saigon and introduce himself to the Viet Minh officials who had taken over from the Japanese. OSS sympathy toward the Viet Minh was well known to General Gracey and he was having none of it. He originally objected to any American presence in the British area believing it was suggestive (of US support for Vietnamese independence), but was overruled by his commander, Lord Adm. Louis Mountbatten. Gracey’s entered into Saigon with a show of force intended to express Anglo-French colonial intentions and to intimidate the locals. On the 23d, he ordered the Japanese to release 1,500 Vichy French soldiers interned since the preceding March; these men were given arms, and under the command of Colonel Jean Cedile took over the Saigon government properties from the Vietnamese. Afterward, the troops went on a murderous rampage, burning and shooting their way across Saigon. The Vietnamese responded by barricading the roads leading into town and firing on anything- or anyone appearing to be to French, including Americans traveling in unmarked Jeeps.

The transition in Indochina was complicated by FDR’s long illness and death in April; (Geoffrey Gunn/Asia Pacific Journal).

A Watershed in U.S. Policy on Southeast AsiaAs the Pentagon Papers reveal, U.S. policy towards France and repossession of its colonial territories was ambivalent. On the one hand, the U.S. supported Free French claims to all overseas possessions. On the other hand, in the Atlantic Charter and in other pronouncements, the U.S. proclaimed support for national self-determination and independence. Through 1944, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt held to his views on colonialism and proscribed direct U.S. support for French resistance groups inside Indochina. By January 1945, U.S. concerns had shifted decisively to the Japanese archipelago, and the prospect of U.S. force commitments to Southeast Asia was nixed, leaving this sphere to British forces. Following the Yalta Conference (February 1945), U.S. planners declined to offer logistical support to Free French forces in Indochina. But the American position came under French criticism in March 1945 in the wake of the Japanese coup de force in Vichy French-administered Indochina leading to Japanese military takeover and internment of French civilians. The American decision to forego commitment to operations in Southeast Asia prompted the Singapore-based British Southeast Asia Command (SEAC) commander Admiral Louis Mountbatten to liberate Malaya without U.S. assistance. At the time of Roosevelt’s death on 12 April 1945, U.S. policy towards the colonial possessions of Allies was in “disarray.”

It took some time for Truman to produce his own foreign policy, he deviated from Roosevelt in that he tended to defer to the Europeans, regardless of their prejudices and follies. He looked to them as counterweights to what was perceived as an increasingly hostile Soviet Union. If the French insisted they needed an overseas’ empire to be successful, so be it. Peasant farmers in faraway Asia were of little consequence to the United States. It would not trouble anyone if they were ignored … or sold out to the French. Washington preferred dealing with partners with whom it had long-standing commercial and political ties; Dewey’s killing did not precipitate the war in Vietnam, but it, and an attack on OSS Capt. Joseph Coolidge a day earlier, suggested the Vietnamese were unreliable and thus, expendable; that they lacked the political and administrative resources to make good on any promises they might make. This turned out to be a disastrous error that compounded over time: the promise the Vietnamese made was to free itself from external rule regardless of cost, a promise that required 30 years and millions of Vietnamese casualties to keep.

Patti:

I found that in 1954 and during the Geneva Conference after the fall of Dien Bien Phu, after the French had been defeated, that we again had a chance to pull out (of Vietnam) and we failed to pull out at that time. This was the third time we had failed to pull out but got ourselves in deeper and deeper. And finally in the 60’s, again, we got involved to the point where it became an American war lock, stock and barrel, which costed us something to the tune of 56,000 men which we left in far away Vietnam, and also to the tune of 300,000 men which are today sitting in veteran’s hospitals maimed, without arms, legs, or sight, or anything else, and in bad shape; plus having torn apart a nation, the United States, which was worse than the war between the states, by the way. It was, it was a terrible situation. No, it need not have happened. It happened. But, we had every reason to not let it happen. Ho Chi Minh was on a silver platter in 1945. We had him. He was willing to, to be a democratic republic, if nothing else. Socialist yes, but a democratic republican. He was leaning not towards the Soviet Union, which at the time he told me that USSR could not assist him, could not help him because they just won a war (against Hitler) only by dint of real heroism.And they (USSR) were in no position to help anyone. So really, we had Ho Chi Minh, we had the Viet Minh, we had the Indochina question in our hand, but for reasons which defy good logic we find today that we supported the French for a war which they themselves dubbed “la sale guerre,” the dirty war, and we paid to the tune of 80 percent of the cost of that French war and then we picked up 100 percent of the American-Vietnam War. That is about it in a nutshell.

Vietnam Syndrome

Senior Chief Petty Officer Scott C. Dayton never got the chance to reflect on the shoes he wound up filling; those of Dewey, Speicher, Spann, the unknown infantryman in Korea; also, the shoes nobody wants to see filled; Losey’s. Dewey’s death represented the swan song of European colonialism in southeast Asia, the question is what about Dayton’s?

Cochinchina is burning, the French and British are finished here, and we ought to clear out of Southeast Asia.

— A. Peter Dewey

By 1965 the United States was firmly stuck in France’s place in the Vietnam quagmire. The ex-schoolteacher unleashed his armies against new students: the ‘peace-time garrison troops, inexperienced and poorly equipped conscripts … ‘ and their incompetent, corrupt commanders and political bosses. it was a lopsided contest the Americans had no chance of winning, this was something even a child could see. The obvious reason is Americans are not Vietnamese, they could never give to the Vietnamese the national identity they already created for themselves. A child could see, but not the American establishment which embarked on self-reinforcing, multi-decade long practice of denying the obvious, an endeavor that continues to this day.

Even as the war was grinding to its bloody climax the Americans believed they were winning, that victory was expected. They argued afterward they were never defeated on the battlefield but this was nonsense, a poisonous, persistent myth. Even American combat successes such as ‘Tet Offensive’ of 1968 turned out to have devastating political consequences in the US. In order to maintain the triumphalist fantasy, the establishment had to find scapegoats on which to pin the defeat: liberals, media, leftists and ‘pointy headed’ Washington insiders; anti-war protesters; dirty, long-haired hippies and pacifists, black nationalists and intellectuals, communist sympathizers and draft-dodging cowards disrespectful of the flag and the troops. These are the same enemies establishment opportunists trot out today; ‘they stabbed America in the back’, preventing the triumph in Vietnam to which the establishment was entitled.

Meanwhile, the war destroyed the American left, which was split between the interests of labor and those who opposed the war on moral grounds. The Left had a proud record of public achievement as it represented efforts to advance the rights of ordinary working people against the entrenched political power of the economic elites. Among its accomplishments, it brought an end to the feudalistic involuntary indentures and debt-driven ‘apprenticeships’ of the early 19th century; freed workers and tradesmen from the banks’ nefarious lending practices and predatory contracts. It took the form of the Abolition movement which brought about the end of chattel slavery at stupendous cost; it ended child labor and gained for America’s youngsters universal, publicly supported education; it earned with blood and ashes the right of labor to organize and gain decent wages and working conditions; freedom from Pinkertons, vigilantes and strikebreakers; to set limits to the commercial power of cartels and the robber trusts.

The American Left opposed US entry into World War One and paid a steep price for it; a war that was started by- and benefited the bankers and big business and nobody else. The American Left was women who gained for themselves suffrage and the right to own property, to sign contracts and hold public office. During the Great Depression the Left’s arm twisting and ordinary Americans’ undermining of finance capitalism wrought the New Deal, a political contract between Americans and the national government: there were jobs programs, pensions for older workers, support for farmers, bank deposit guarantees, protection from financiers … for both citizens and for finance itself. The left’s public shaming and the efforts of black Korean War veterans made civil rights the law of the land for all Americans. With the Vietnam war, organized labor embarrassed itself in its haste to scramble to the side of the war makers; like so many others it had become another corrupt and spineless vested interest. Both the labor bosses and the rank-and-file felt there was too much to lose by appearing to be unpatriotic; they stood off to the side and wrung their hands as the war swallowed hundreds of thousands of young Americans. As penalty for cowardice, labor was quickly castrated by big business and by the 1980’s had become a shadow.

The anti-war Left was reduced to a single issue advocacy group aiming to end the war. It was easily marginalized; after all, who were the advocates? Liberals and insiders; anti-war protesters, dirty hippies and pacifists, etc. It didn’t matter history was at their backs and that the establishment had failed. Without the war, there was no point to the advocacy, it was path-dependent; even as the right was deprived of its victory by the Vietnamese, the end of the war deprived the left of what had become its reason to be.

Believing the victory it was entitled to had been snatched away, the establishment directed the county’s energies into running it down wherever it might be found: trolling the ghosts of Vietnam, decade after decade, in country after country, war after fruitless, pointless war, in Iraq and Afghanistan, in Iraq again and now Syria, against enemies foreign and imaginary, war against itself in the end …

… But by her still halting course and winding, woeful way, you plainly saw that this country so wept with blood still remained without comfort. She was America, weeping for her victories, because they were not.

Note about comments.

Comments are encouraged; please be on topic, tactful, etc. Any comment that is discriminatory, hateful, ad hominum or meant to ‘troll’ or annoy will be deleted and the user banned.

Originally, this installment was going to be about the Kurds in Syria; it is clear the Kurds have discovered their own national identity which will be revealed to all in good time, hopefully without too much bloodshed. Like the Vietnamese in 1945, they promise never to submit to external rule. In dark times like these, this is refreshing; if poor Kurds can refuse to submit so also can the rest of us.