The real estate recovery has gone missing. Someone should call Sherlock Holmes. Perhaps he can find it:

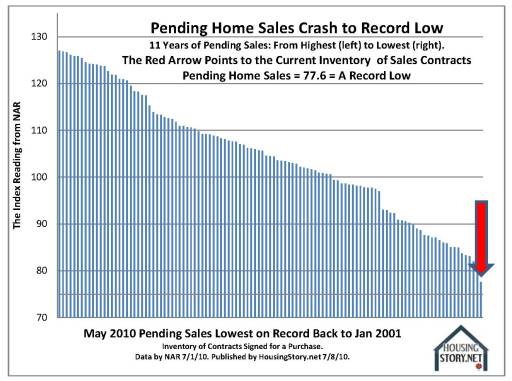

Pending Homes Sales Crash in a Record Fall to a Record Low as Tax Break Expires

The Index of pending home sales fell a record 30% in May to a record-low reading of 77.6 — two huge pessimistic indicators of future prices nationwide. Yet the combination of two record negatives went barely reported when the stats were announced last week.

So here’s the news for you now, a week late, but new to the marketplace of ideas. Pending-home sales now stand below the worst numbers we have seen since the housing crash started in 2006. The rubber bands and duct tape are breaking apart. Presume the fix of a fall is in.

Take a look at the three charts below and judge for yourself how important the facts are which the National Association of Realtors (NAR) announced last Thursday (July 1st).

We are in a pause of a tectonic shift of plates. Prices have been flat since August 2009, but are down 30% from their peak. The fall of 30% was almost completely discounted as impossible prior to its occurrence.

My speculation is that the fate of bubble-mortgage debt remains as our key obstacle blocking recovery (Unbelievers should rent the Godzilla movie “Eating the Lost Decades of Japan” for further enlightenment.). Total mortgage balances remain almost unchanged from the peak of the bubble –$11.68 trillion today versus $11.95 trillion at the peak (see chart below).

Where is the chart? Somebody stole the chart!

The data released last week on pending home sales and the dismal record of reporting on that data proves that breaking news business journalism fails even in surface scratching. The cows just want to feed on the grass in front of them and go on to the next field.

The smart investor is going to look at these charts on pending-home sales and have a real advantage over the common media consumer. Readers of my work know I have found pessimistic facts easy to find. The pending-sales figures are a dramatic concurrence — a record fall and a record low.

So I will give you my opinion: All hell has broken loose all over again in real estate. Don’t buy a home. Sell one.

Here is the missing chart:

Over @ Automatic Earth where I discovered the original article and Holmes found the missing chart, Ilargi fulminates:

That is, what Americans’ homes are worth, their equity, decreased by $7 trillion -from $20 trillion to $13 trillion-, from spring 2006 to spring 2010. In the same period, mortgage debt, what Americans owe on their homes, went down by only $270 billion. Yes, that’s right: US homeowners lost more, by a factor of 26, than they “gained” through clearing mortgage debt. Thus, if we estimate that there are 75 million homeowners in America, they all, each and every one of them, lost $93,333.

Good morning America!!

And your own government is still trying to encourage homeownership? Now why would they want to do that in the face of numbers such as these? How much thought have you given that question? Over the past 4 years, the “right to own a home” has become synonymous with the “right” to lose some $25,000 a year. Why does Washington, through Fannie and Freddie, Ginnie Mae and the FHLB, continue to guarantee guaranteed losses for American citizens?

Since the US has become the embodiment of Jesse James and Al Capone the cycle works like this:

1. Enable trillions of dollars in mortgages guaranteed to default by packaging unlimited quantities of them into mortgage-backed securities (MBS), creating umlimited demand for fraudulently originated loans.

2. Sell these MBS as “safe” to credulous investors, institutions, town councils in Norway, etc., i.e. “the bezzle” on a global scale.

3. Make huge “side bets” against these doomed mortgages so when they default then the short-side bets generate billions in profits.

4. Leverage each $1 of actual capital into $100 of high-risk bets.

5. Hide the utterly fraudulent bets offshore and/or off-balance sheet (not that the regulators you had muzzled would have noticed anyway).

6. When the longside bets go bad, transfer hundreds of billions of dollars in Federal guarantees, bailouts and backstops into the private hands which made the risky bets, either via direct payments or via proxies like AIG. Enable these private Power Elites to borrow hundreds of billions more from the Treasury/Fed at zero interest.

Etcetera …

Over on the non- fulminating ice flow Steve Randy Waldman makes this observation:

Even today, now that it has all come apart, economists maintain a laser-like focus on the stickiness of wages. Why can’t Greece compete? Because its “cost structure” has grown too high. In English, that means people expect to be paid too much. The solution is “adjustment”: workers’ real wages must be reduced to restore competitiveness. American economists, following in the footsteps of Milton Friedman, trumpet the glory of floating currency regimes, with which one can reduce the wages of a whole nation of workers with a single devaluation (and without the workers having much opportunity to object). The Greeks, of course, must suffer, because they are part of a fixed currency regime, and workers and employers are unable to organize the universal wage collapse that would be good for them in the way of vegetables at the dinner table.

Now, not all economists are heartless. Left economists love workers. They urge governments to devalue if possible, to chop the broccoli into chocolate cake and hope that nobody gags. These economists rail against the fixed exchange rates, because nominal wages cuts usually occur only alongside the human tragedy of unemployment. They beg governments, if they can, to just borrow money and pay workers their accustomed wages (to do some important thing or another) and hope that things work out well.

But it is always about the workers. Workers are the core problem. Macroeconomic policy, as a practical matter, is mostly about finessing “rigidities” associated with workers’ stubborn wage expectations.

Yet there is an even stickier price in the economy, a price economists have mostly ignored although it is at least as ubiquitous as wages. The price of a past expenditure, the nominal cost of escaping a debt, is fixed in stone the moment a loan is made and then endures in time, perfectly rigid, while the economy fluctuates around it. It is certainly a price, but can only be made flexible via bankruptcy — a disruptive institution, rarely modeled by macroeconomists, and rarely deployed at scale. Surely, the price of manumission must be as nimble as the price of petrol if the economy is to keep its equilibrium while being battered and buffeted by shocks.

There is nothing like a large loan encumbering a property to fix its nominal and real price far above any ‘equilibrium level’. Until the debt price retreats to a level serviceable by production the outcome is broken balance sheets and bad banks:

Of the 986 bank holding companies in the US last year, a total of 980 of them LOST MONEY. And that’s even after all the government bailouts the sector received. Hmmmm. Robust banking recovery? Not a chance.

Of course, if the house prices fell to a market- clearing level all 980 bank holding companies would simply go out of business. Quite a conundrum, no? Damned if you do, damned no matter what happens!

Here is an observation by Barry Ritholtz:

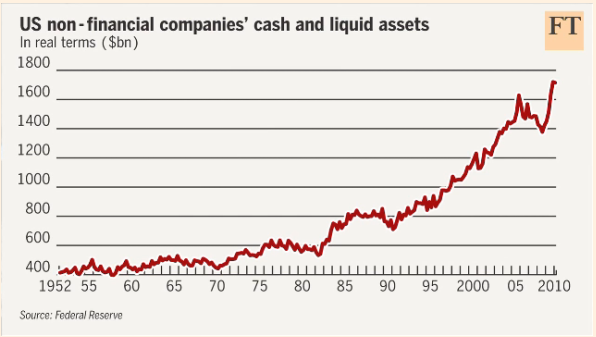

The average cash-to-assets ratio for corporations more than doubled from 1980 to 2004. The increase was from 10.5% to 24% over that 24 year period. That was the findings of a 2006 study by professors Thomas W. Bates and Kathleen M. Kahle (University of Arizona) and René M. Stulz (Ohio State). When looking for an explanation, the professors found that the biggest was an increase in risk.

Indeed, the phenomena of corporate cash piling up has been going on for a long long time. You can date it back to the beginning of the great bull market in 1982 to 86, went sideways til the end of the 1990 recession. It has been straight up since then, peaking with the Real Estate market in 2006. The financial crisis caused a major drop in the amount of accumulated cash, but it has since resumed its upwards climb.

This FT chart makes it readily apparent that this is not a new trend:

>

chart courtesy of FT.com>

2) The total cash numbers numbers are somewhat skewed by a handful of companies with a massive cash hoard. Exxon Mobil, GE, Microsoft, Apple, Google, Cisco, Johnson & Johnson, Verizon, Altria, EMC, Disney, Oracle, etc.

3) Not only is this not new, but the media has been covering it for years. See for example, this 2006 USA Today about the same phenomena: Many companies stashing their cash. Or this 2008 Businessweek article: Stocks: The Kings of Cash. Or this 2009 WSJ article: Corporate-Cash Umbrellas: Too Big for This Storm?.

And yet another take from Mises Institute, where Predrag Rajsic observes the direct relationship between production and aggregate demand is in the form of a feedback loop:

In order for this labor to be available at another point in time, when the (exogenous) propensity to consume returns back to the level needed for full employment, these unemployed laborers need to have some nonzero level of consumption while being unemployed. Let CU = e∙N1 be this minimum consumption, where e is the physical quantity of output needed to sustain the life of an unemployed person.

But consumption of the unemployed is not met by an equivalent expenditure because unemployed labor does not earn income. This physical output must be given to the unemployed without monetary compensation. However, nowhere in this model is it specified that there is some surplus production of physical output that will be given away to the unemployed without monetary compensation. Thus, it seems that the model assumes zero consumption for the unemployed, which directly implies that the unemployed will not be able to sustain their physical existence in a prolonged recession.

In order for this situation to move towards equilibrium, the propensity to consume of the employed and the employers needs to be reduced below pc1 to meet the consumption needs of the unemployed. However, propensity to consume is an exogenous variable and is not a subject of individual choice in this model.

Even if propensity to consume was subject to individual choice, a further reduction in the propensity to consume would only lead to more unemployment and disequilibrium — since the reduction in the propensity to consume, according to the model, caused the recession in the first place. The only stable equilibrium in this situation is zero output for the whole economy, which amounts to a complete annihilation of the economy. Therefore, we cannot assume that the consumption of the unemployed is not included in the expenditure of the employed.

All these different observations are linked even though there is no obvious connection among them other than the missing economic recovery. But look: housing debt is certainly sticky and the ability to remove the burden of non- payable debt is held hostage by the income streams the mortgages themselves represent. Meanwhile, other incomes streams from more or less the same source – consumer spending – has been aggregating in the bank accounts (or mattresses) of business corporations. This aggregation is ALSO sticky and increasing. This factor is not a part of the banks’ business model as the business corporations have successfully passed their various risks to their own banks! At the same time, the sticky business aggregation has not arrived in the standard equilibrium model seen in both Keynesian or Austrian systems.

Waldman (via Rob Parneteau) comes to much the same conclusion by way of Wynne Godley:

Now we can tell what I think is a much more informative story. It is not the “private sector” whose financial position needs to improve. Businesses exist to increase the value of their liabilities to shareholders and creditors. They do not “delever” by reducing the sum of those liabilities. “Leverage” properly refers to the ratio between different sorts of liabilities, debt versus equity, not the total quantity of claims. In a good economy, the financial indebtedness of business entities will be increasing, as the value their real assets grows! Growth in the “net private sector financial position” could come from an increase in household income (yay!) or a decrease in the value of real business assets (yuk!). We certainly shouldn’t make policy decisions based on promoting or accommodating such an ambiguous outcome. Instead, we should craft our policies to be consistent with what we actually want, which is household financial income. (Note that this analysis necessarily excludes nonfinancial income, such as unrealized gains or losses on the value of a home.)

Reviewing equation [17], there are three ways a nation can improve the financial positions of its household sector. It may (i) run a current account surplus, usually by exporting more than it imports; (ii) have the government run a deficit, improving household financial position by having the government run a deficit, or (iii) increase the value of business nonfinancial assets. Approach (i) can’t work for everyone, of course. Assuming external balance, it is obvious (at least to me) that approach (iii) is ideal. Parenteau, I think, agrees:

Remember the global savings glut you keep hearing about from Greenspan, Bernanke, Rajan, and other prominent neoliberals? Turns out it is a corporate savings glut. There is a glut of profits, and these profits are not being reinvested in tangible plant and equipment. Companies, ostensibly under the guise of maximizing shareholder value, would much rather pay their inside looters in management handsome bonuses, or pay out special dividends to their shareholders, or play casino games with all sorts of financial engineering thrown into obfuscate the nature of their financial speculation, than fulfill the traditional roles of capitalist, which is to use profits as both a signal to invest in expanding the productive capital stock, as well as a source of financing the widening and upgrading of productive plant and equipment.

What we have here, in other words, is a failure of capitalists to act as capitalists. Into the breach, fiscal policy must step unless we wish to court the types of debt deflation dynamics we were flirting with between September 2008 and March 2009. So rather than marching to Austeria, we need to kill two birds with one stone, and set fiscal policy more explicitly to the task of incentivizing the reinvestment of profits in tangible capital equipment.

So what is the role of approach (ii), which stimulus proponents and MMT-ers frequently advocate? Note how Parenteau phrases things: because “capitalists [fail] to act as capitalists”, because businesses are not increasing the value of their nonfinancial assets, fiscal policy must be employed to avoid “debt deflation dynamics”. Here we reach the formal limits of the sectoral balance approach. This style of analysis gives us no insight into the dynamics or distribution of financial positions within any of the categories we have carved out.

In other words, businesses hoarding cash are also hoarding a large part of any economic recovery!

Policy would look well toward motivating that corporate cash to assist in the resolution of the mortgage sector, keeping in mind that housing prices are simply too high to be affordable and that the lending encumbrance is self- defeating for the entire industry. Within the current housing/lending dynamic the only stable equilibrium … is zero output for the whole real estate sector, which amounts to a complete annihilation of the sector!

Holmes would suggest that the business companies are simply waiting for this turn of events so that they might buy everything for next to nothing, as in the early 1930’s. Here we see the current/future US hard- dollar economy in action! While not directly responsible for the dynamic – that being peak oil and the fixing of money value (dollars) to an invaluable input – they are certainly not above taking advantage of it!

It would certainly not be too difficult to make business companies offers they cannot refuse. At some price level, housing investments cannot fail to make money. This level does not have to be zero, yet the overall price levels must be reduced to affordability. This is a matter of coordination and some subtlety; aligning the ‘propensity to consume’ at the lower nominal (and real) levels with the anticipated returns such consumption allows. The practical matter is to recognize the tactics and not allow the dynamic’s effect to materialize. By doing so the dynamic itself is moderated as Rajsic’s article suggests.

Resolution would recognize that real estate values are far from zero but that some are relatively greater than others for reasons relating to energy return on energy/capital invested. Current loan values are fixed by speculation and the energy hedge that speculation represented in the past. Since the hedge dynamic is a ponzi or pyramid scheme, there is no value that can be obtained from artificially attempting to maintain these price levels.

On the other hand, the hedge has defeated itself as it demands ever- higher levels of uneconomic energy consumption to make any practical use of it. Without the potential hedge return the aggregate consumption penalty makes the entire enterprise unaffordable; another set of economic utilities must be established. It is only the current consumption prejudices which gave rise to the lending- pyramid hedge in the first place that stands in the way of re- evaluating both real estate utility and business cash acquisitions more practically.

As a waste platform, the ‘highest and best uses’, aren’t.

The mechanics of resolution are straightrforward. Real estate loans would be disgorged from banks and investors and recognized at market value. Those establishments with no other business but real estate lending would be liquidated, all would be paid a market rate with losses accepted. Stockholders would be wiped out, bond holders positions converted to equity, the restructured loans would be bought by business corporations in lieu of an interest penalty on cash holdings. At some level a market for housing would form, the business cash injection would allow an investment in walkable communities and the non- performing, auto- centric ‘developments’ bulldozed into farmland or resource recovery areas.

Putting business cash hoards into the service of production would serve the interests of business whose rigidities are currently those of the ossifying auto empire; it is no surprise these companies see no investment opportunities! Real estate has been the largest element of the consuming world for decades, reconfiguring real estate away from the auto and work away from automation are millenial challenges. The work to be done is immense. Producing an income stream that is sustainable by way of conservation – businesses purchasing conservation by way of husbandry – is a better way to mitigate some of the land mines that our previous over- consumption has laid for us.

You don’t have to be Sherlock Holmes to figure that out.