A lot of talk about the WTI-Brent price spread:

Canadian crude surge on record WTI-Brent spread (Reuters)Canadian crude oil prices surged on Tuesday in reaction to a record spread between U.S. and world benchmarks, market sources said.

Western Canada Select heavy blend for October fetched $7.05 a barrel under benchmark West Texas Intermediate, its narrowest margin in 15 months of Reuters data. That compares with $11.50 under WTI in the middle of last week.

Light synthetic for October was quoted at $12.15 over WTI, compared with $11-$11.45 over last week.

Brent rose on Tuesday, while WTI tumbled more than $2 a barrel, pushing the differential between the two past a record $27.

Beginning of the year was $10 with lesser quality Brent being priced higher than light, sweet Cushing crude. What’s up with that?

Theories abound, here is Bruce Krasting’s tale of market manipulation:

What is very clear is that the cost of crude used by US refiners to produce gasoline has nothing to do with the WTI price. LLS pricing has been running a $3-4 premium over Brent for some time now. That, to me, makes perfect sense.A shipment of Nigerian crude (sweet) has two destinations. One is Rotterdam, the other is the GOM (Louisiana offshore delivery). The shipping cost for GOM delivery of a VLCC (1mm barrels of crude) is about $4/Brl higher than for European delivery (4-6 extra days of transit). Therefore a pricing matrix where LLS is equal to Brent +$4 is consistent.

The price of gasoline for much of the country is driven by crude pricing in the Gulf; not Cushing, Oklahoma. At yesterdays closing price for LLS the price of gas is going higher in the USA. So another big drag on the economy is in front of us.

Some thoughts on this.

A few months back the smart folks at the Department of Energy tried to influence the LLS pricing by releasing crude from the SPR. That worked, for about a week. The LLS/WTI spread was about $15 at the time. Given that it is much higher today I think it is possible that D.C. will again choose to sell some more of the strategic holdings of crude in an effort to create a cheaper cost for gasoline. If the DOE was in for a penny in June then they should be in for a pound (or two) right now. One can be sure that the interventionists in Washington are teeing this up as I write.

… then there is FT Alphaville’s of … market manipulation:

The Fed’s oil easingIzabella Kaminska

This post is going to address two fundamental points:

1) Why it might make sense for the Fed (or a respective government agent) to intervene in commodities.

2) Whether the Fed has indirectly already intervened and does this explain the mysterious WTI-Brent disconnect?

While we appreciate the above might be considered controversial, we would say exceptional circumstances call for exceptional reactions. What’s more, official mandates have hardly stopped other central banks from breaking them (ECB, ahem).

There are three other points:

First, there is a precedent for the Fed using derivatives. Second, the Fed’s mandate is focused on price stability and moderated long-term interest rates. Third, other governments intervene in commodities all the time. And last, there is already a precedent for the US government intervening in commodity markets in a bid to change inflation expectations.

Not to mention the fact that the Fed has a specific portion of its balance sheet assigned to “inflation compensation”. That is, its balance sheet adjusts to account for increasing inflation expectations as related to its Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPs).

Kaminska’s theory is that the Fed is using the commodities markets to offset effects of its Treasury purchases. She suggests that the central bank(s) is in the process of outwitting itself, hedging then counter-hedging:

The Fed’s oil easingWhen it comes to financial speculators, however, there is no natural counterpart. An inflation-hedging financial speculator can only attract a counterparty if he compensates them for the risk they’re taking on by holding the opposite position. Thus, in an inflationary environment, the natural shape of the energy ‘yield curve’ begins to slope upwards (takes on a contango formation). Financial speculators have to overpay (or pay a risk premium) with respect to the spot price. They’re happy to do this, because ultimately they believe the inflation risks will eventually compensate for the premium they pay today.

Arguably, this sort of contango situation suited the Fed just fine up until this year. The deflationary risk was being disguised by the inflationary view of the energy curve. What’s more, the contango formation was signalling a glut of supply to the market, keeping spot prices suppressed and away from demand destruction territory.

If this was an active policy, one might call it energy curve targeting.

The Cushing factor

If the above is true, then when it comes to the WTI, a small contango is beneficial, too much of a contango is dangerous and backwardation itself is lethal (since it implies the opposite, a speculative deflationary view). It’s here that Ochoa-Brillembourg’s point resonates well. If the Fed’s monetary tool box has run out of power due to the natural restrictions found in the Treasury market, it stands to reason that the Fed (or a respective government body or private sector partner) could be tempted into targeting the energy curve instead.

All of the incredible readers here in the Undertow look at backwardation as dangerous for its deflation implications. A reasonable question would be, is the Fed manipulating an important market to keep it from sending the wrong signal about ‘the economy’?

Keep in mind, the only thing the central bankers know how to do is give money to banker ‘buddies’ and then look the other way as these ‘buddies’ run off to tax havens with it. However, the Fed might try to do some cheap monetary policy by ‘purchasing’ the entire futures market for Treasuries by taking large on long positions (at a cost far more modest than buying actual Treasury issues). This can be called ‘Back Door QE’ and would be right down the Fed’s ‘give money to bankers’ alley.

The Fed could buy futures contracts with the interest it ‘earns’ in its massive asset portfolio. Not all of Bernanke’s loans are bad, just most of them! Instead of using revenue to buy an insignificant amount of Treasuries directly it could use futures market to push the price of Treasuries (the same way the Fed pushes the stock market by purchasing S&P 500 futures contracts). All that is needed is an equally large market (or markets) to lay off risk, since:

… when it comes to financial speculators … there is no natural counterpart. An inflation-hedging financial speculator can only attract a counterparty if he compensates them for the risk they’re taking on by holding the opposite position.

The ‘counterparty risk’ can be compensated for by selling WTI futures in sufficient volume to move the market!

Notice that the margin requirements for Treasuries have not been changed while those for the benighted gold contract are ratcheted upward every fifteen minutes or so …

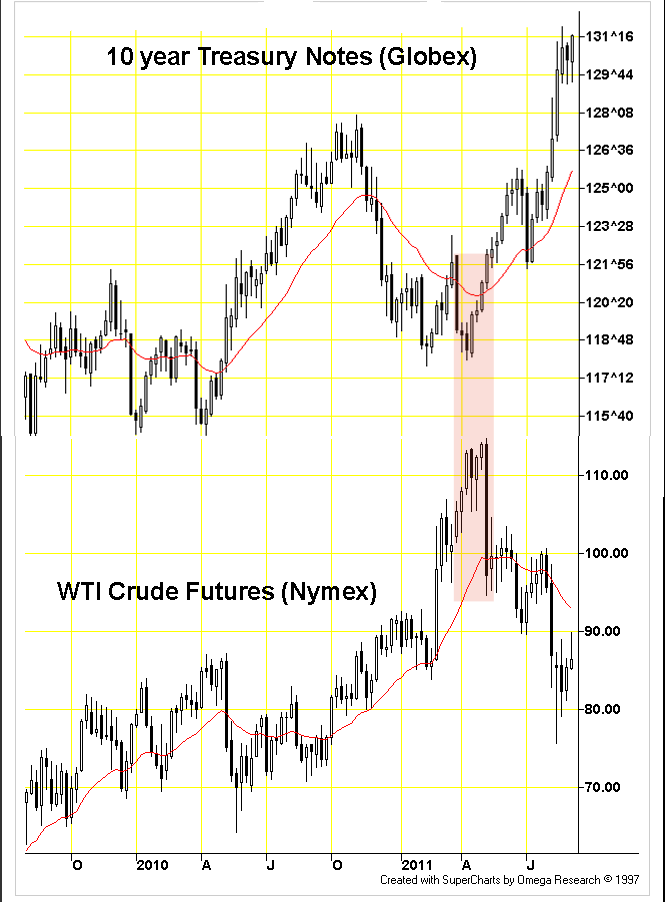

Here is the weekly futures chart of the 10-Year T-Note superimposed over the WTI. The red area is the time period when the market started repricing the wind-down of QE2 (Click on chart for big):

This ‘chart’ is from TFC Charts: Notice the reverse correlation that began during the summer, when traders began to price in the end of QE2.

There is little fundamental reason for Cushing crude to be $27 cheaper than Brent or Gulf of Mexico crudes. The refiners are paying the world price of (roughly) $115 per barrel. Cushing is a captive market where contracts can be sold but delivery is constrained. Physically arbitraging Cushing and Louisiana crudes is difficult because there is insufficient pipeline capacity.

It looks here that Treasury futures are driven by Fed purchases (to some unknown degree) and Eurozone flight to safety. Both or either of these dynamics are pushing hard on Treasury futures, the same way they are pushing on gold/silver futures. Laying off the risk requires a market that can also be pushed: the Cushing market.

All this is beside the point: if world crude prices were $80 per barrel, the stress on industrial economies would be much less than it is now. At the Brent price, there is little hope for an outcome that includes pointless waste in exchange for minuscule profits for a handful. It’s a matter of who — or what — goes ‘belly up’ first.

Greece … or Switzerland?

Who knows?