Figure 1: Unsupportable cost of fuel at $125-per-barrel is the bridge too far. Chart by TFC Charts.

Prices for crude oil are both too high and too low at the same time. High prices are eroding demand while too-low prices threaten petroleum production.

It appears the bear markets for crude since 2008 is still in force. There is little buying pressure above $125 per barrel. It is possible for a catastrophe to destroy demand worldwide but rather it is likely for a retest of the $125 per barrel price one more time in the near future. within six months or a year. After that the price will decline because the world’s credit system will be visibly coming apart at the seams and demand in the major consumer countries: Japan, US, China, India and EU will be collapsing.

This demand unraveling is taking place right now and the process will accelerate as the historically high real crude prices bankrupt demand not just temporarily subdue it: note Spain and Japan.

Without credit and customers the auto industry will consolidate: nations whose output is dependent upon auto manufacture and sales will be unable to service debts taken on to support the industry. Since auto manufacturing and its real estate and construction dependencies is the world’s single largest enterprise, failure of large components will have outsized negative effects on GDP. These effects in turn will feed back into manufacturing in an accelerating vicious cycle.

Meanwhile, the decline in fuel barrel prices below cost of extraction will cause fuel shortages. This is why every decline in fuel prices is dangerous as the lifting cost for new crude oil and ‘substitutes’ is already at the threshold of what customers can afford to pay.

Demand is financed until costs become breaking. Last spring when crude prices skyrocketed there were riots around the world as fuel-related costs made food unaffordable. Who paid the ‘ultimate price’? Greeks, Egyptians, Syrians … of course, their demand is now exported to core states such as the US.

Conventional analysis suggests that declining prices are good for the (waste-based) economy, of course they are! Here is some ‘Brand X’ analysis:

Oil prices edging downward bodes well for U.S. economy

Brad Plumer (Washington Post)

Oil markets appear to have stabilized in recent days, thanks to a boost in output from Saudi Arabia and other crude producers, according to two new reports.

Many car-industry analysts, for example, have been encouraged by the strong U.S. auto sales in March. But they warn that if gasoline prices stayed high, those sales could drop in the months ahead as consumers put off new vehicle purchases.

“If gas prices were to keep rising, that would eventually cut into overall sales,” said Sean McAlinden, an economist for the Center for Automotive Research.

Of course, even if the oil market stabilizes, prices will remain relatively high by historical levels: Adjusted for inflation, crude prices are higher than they were during the oil shocks in the 1970s.

But there are some signs that the U.S. economy is slowly adapting. James Hamilton, an oil expert at the University of California at San Diego, has long argued that oil prices mainly only cause serious economic harm when they reach new peaks. When that happens, consumers tend to get nervous and put off buying automobiles and other goods. Yet if oil prices are merely returning to previously highs — as is the case right now — then the impact is blunted.

Still, Hamilton’s research also suggests that drops in the price of oil have only modest effects. “One very well-established observation,” he has written, “is that although oil price increases were often associated with economic recessions, oil price decreases did not bring about corresponding economic booms.”

What conventional analysis does not grasp is demand is satisfied in one place at a relatively low cost because demand elsewhere is quashed. The wider dynamic has the US driver paying less for gas because the driver in Spain has no gas at all. When the Spanish economy collapses the demand represented by Spanish drivers is permanently exported to the US. Yes, this comes across as ‘good’ for a handful of auto manufacturer executives: failure in Spain is ‘good’ for the economy as a whole only to the point when US drivers cannot bid for fuel themselves … because of problems in Europe.

This point is accelerated by failures outside the United States: the world economy does not exclude the US when it is convenient for American motorists.

It never occurs to analysts that the price fails to reach the very highest levels or remain there because the economy outside of the gasoline pumps is malfunctioning. This incredible malfunctioning effect is due to the fuel prices that are high enough to discourage customers but not high enough to represent an actual fuel price shock. Fuel demand is inelastic until it blows up, then it is gone. The decline emerges in final demand for all goods and services not just fuel. Here is crowding out as funds flow toward fuel away from items that embed it … items that also have become too expensive!

Instead of a consumer paradise that continually offers ‘having it all’ the consumer must prioritize within a shrinking budget. He can afford to fill his tank but will not buy another car or a new house (particularly if he hasn’t paid off the first car and is underwater on the old house).

This dynamic is in place right now, not in some uncertain future as suggested by economist McAlinden, perhaps not in his town but certainly elsewhere in the greater world.

Prices decline due to the refusal/inability of customers to meet them: when customers don’t pay for long enough time (and credit lines are exhausted) businesses fail. In 2008, thousands of (real estate related) firms that were dependent upon $20 per barrel fuel failed along with a large part of suburbia itself: there is no more $20 fuel. In 2012 these firms are gone and the economic necessity of $20 fuel for the entire economy is reduced. Businesses can cope with higher prices but not the highest prices: enterprises dependent upon $75 and $90 fuel are under price pressure as customers retreat. These enterprises include fuel producers themselves which see shrinking profit margins.

According to the conventional analysis the declining prices are always positive like sunshine. Extended sunshine is a drought. Declining prices make finding and lifting fuel unaffordable. Analysts focus on minuscule changes in output here and there while ignoring the overall trend of flat output and the inability of credit-rationed demand to fund the extraction of new ‘unconventional’ oil to replace what is already gone.

The problem is structural, there is less fuel available everyday relative to relentlessly increasing demand. Supply has leveled off. The end of the day has zero-available fuel at a price that anyone can afford. The outcome is national bankruptcy as is seen in Greece: which country fails last is meaningless. Without substantial changes in attitudes, all the countries, one after the other will fail. The marketplace hasn’t begun to explore the meaning of the term ‘permanent shortage’ which is going to emerge as a rude shock to all concerned.

Conventional analysis insists that the central banks are printing money and the result is hated cost-push inflation. If this was so prices would never decline as long as new money was being created and in fact, new money is indeed being created … just not by central banks.

$200 Oil Coming As Central Banks Go CTRL + P Happy

Submitted by Tyler Durden on 02/24/2012

We have been saying it for weeks, and today even the WSJ jumped on the bandwagon: the sole reason why crude prices are surging (RIP European profit margins: with EUR Brent at a record, we can only assume the ECB will pull a 2011 and hike rates in 3-4 months even as it pumps trillions in PIIGS, banks bailout liquidity) is because global liquidity has risen by $2 trillion in a few short months, on the most epic shadow liquidity tsunami launched in history in lieu of QE3 …

During credit expansions, all else being equal, prices increase along with the ability of the users to meet the price. Ipso facto the prices would not rise otherwise.

Fuel has become unaffordable as the ability of users to meet fuel price diminishes as most use of fuel does not produce a return. Currently, taking on more debt does not produce a return, either. This can be thought of as a credit-driven ‘reverse wealth effect’. It is fuel rationing by diminishing productivity of credit.

Central banks are collateral constrained, they cannot print money: they cannot create new money. The Federal Reserve Bank/System is a reserve bank not a commercial bank. Central banks do not make unsecured loans, they cannot or they cease to be central banks. It is hard to believe that anyone would think that central banks make unsecured loans. If they did so there would be no central banks and the entire credit system would have collapsed a long time ago.

Central banks validate collateral. For them to do otherwise would have money panics without end as there would be no lenders of last resort. No collateral would be worth anything during periods when worth of collateral is most challenged.

Here, the correspondent bank demands collateral from a client bank which is technically insolvent. Because the client cannot offer sufficient collateral the request for credit is denied.

The central bank makes the same demand for collateral even for overnight loans. Central banks are risk intolerant and cannot extend unsecured loans. Central banks can extend credit against impaired collateral but cannot do so against no collateral. Because loans by the central bank are collateralized, the balance sheet of the central bank is always (theoretically) balanced.

Meanwhile, the balance sheet of the central bank expands because balance sheets elsewhere within the private sector contract. When private sector balance sheets are expanding there is no central bank lending, in fact no need for it! Because there is no ‘new money’ from the central bank there is no funds to push prices. If prices are being pushed it is because prices for other goods, elsewhere are left alone.

At the end of ‘It’s A Wonderful Life’, George Bailey’s bank is bailed out by depositors just like in the Real World. Unlike the real world, the depositors in the movie are overjoyed to have the opportunity to bail out a bank. Keep in mind, neither Bailey’s nor Potter’s banks will grow in the conventional sense — neither will the economy — unless they both extend unsecured loans to borrowers without collateral. Creating unsecured credit — printing money — is the function of commercial banking, the credit markets and finance. So far, this establishment has done a good job: generating $55 trillion in US total debt, most of it since 1980.

It’s A Wonderful Economy: what is there to show for these trillions? A trillion barrels of crude oil has been ejected worthlessly into the atmosphere along with billions of tons of other irreplaceable resources! Not only was the debt taken on for nothing, so is the fuel burned and the resources wasted. Who benefited by way of this wonderful process? A handful of ‘Prominents’ and ‘Kombinators’ died rich …

Governments can print money — issue fiat currency without liability — but they universally refuse to do so. This is because governments are dependent upon the banking system and because organic credit is the foundational condition necessary for industrialization. The reason there is increased liquidity is because the private finance sector has increased unsecured lending.

The government promotes risk socialism. Finance doesn’t need any help raising money, it only needs a sanction and a permanent deficit somewhere within the economy, this deficit is a service of the government. Finance feedbacks are faulty: prices rise due to increases in private credit until something breaks. Here is where the financial philosophy of ‘no limits’ reaches limits. What risk socialism means is that any breakage is not the responsibility of finance but of happy depositors. This is the sanction that allows finance to make new loans: ‘other peoples’ money’ that is Occupied by One-percenters.

The banks lend to fund asset speculation: prices rise because it theoretically isn’t different this time! Every recession in US history has ended with market expansion and increased credit availability across the board. It is reasonable for credit providers — and markets — to assume that credit demand will increase as it has after previous recession. The ongoing increasing government(s) deficits assure a corresponding increase in private surpluses (wealth). At bottom, nothing matters other than increased wealth for the well-connected at all others’ expense.

The auto industry has the capacity to provide every human a new car. The ‘home-building’ industry can house all 7 billion of us. The problem isn’t capacity. There aren’t enough humans with something of worth to offer in order to keep the current capacity effectively utilized. Something to offer in this case means credit worthiness. Ours is ‘Planet Deadbeat’. Most of the world’s citizens are not just broke but negatively wealthy – under water. Those who aren’t may as well be, they won’t spend. The problem is that the private sector loans to fund fuel waste cannot provide a return so that additional lending is necessary. Finance clients burn capital and go into debt in order to do so. As finance extends new loans they are extending new bad loans. None of the loans can be repaid and the disappearance of capital insures there will be less credit available for any purpose in the future (including to fund conservation).

It is important not only to be aware of events taking place in the Eurozone but also to watch Japan. The costs of fuel have been supported in Japan by its industrialists’ ability to transform some of Japan’s fuel imports into exportable high-worth goods such as automobiles and personal electronics. Unfortunately, Japan’s establishment has painted itself into a corner as the auto business works at cross-purposes to push its own real energy costs past the point of affordability. Meanwhile, the personal electronics train has left the one-time Japanese giants behind. For instance, legacy ‘innovator’ Sony has surrendered its once-lucrative Walkman franchise to Apple. Post-Fukushima, the timing is terrible for Japan which needs some sort of export surplus to afford to remediate its reactor problems.

Unfortunately, Japan is condemned by conventional analysis. If it continues to gain an export surplus Japan will use it to subsidize more counterproductive ‘growth’ and leave the reactors to tend to themselves.

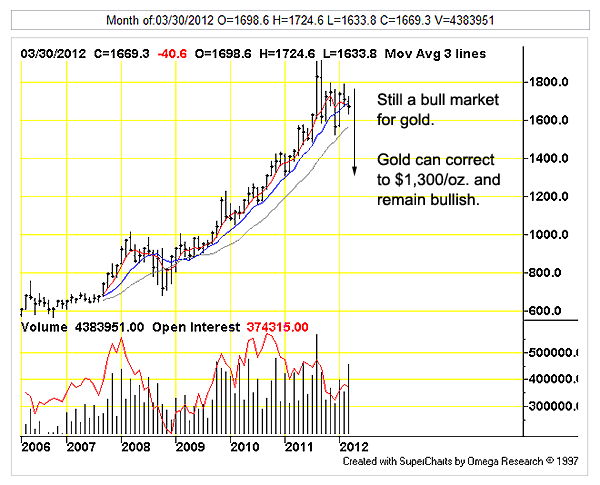

Figure 2: Gold futures continuous monthly chart from TFC Charts. Gold ‘investors’ are having fits because the price doesn’t continue to skyrocket as desired. Instead, the gold market is taking a breather. Right now there is no reason to believe the gold bull market has ended as conditions that would support a bull market are still in force.

Keep in mind that the gold futures market is becoming a general purpose hedge for currency trade around the world. That this is so is manifested by efforts by governments in India, Turkey and Vietnam to ‘manage’ domestic bullion trade for currency reasons. It is likely that institutional currency traders are using the gold and silver futures markets to do the exact same things (but on opposite sides of the trades).

The biggest issue in the gold market right now would be the euro and what it is really worth. The currency market says the euro is worth $1.31. The banking and credit system suggests (insists) the euro is worth $0.00. The petroleum market says something important is going to die: $125 allocated for each barrel has to be diverted from some other account. At the same time, euro-stress on euro-banks means the hunt for capital is on. This leads to margin calls and forced sale of assets which includes gold held by banks. Unsurprisingly the market for gold is being pulled in all directions and the price moves are sideways within a period of correction/consolidation.

As the problems in Spain emerge and the French elections take place there will be more asset dumping, there will also be a flight out of euros and toward safety. The net result will be less credit available and deleveraging across the Eurozone.

The real bottom: nothing matters other than the world is running out of cheap petroleum. What remains is unaffordable.