Summer doldrums are here, the modern world slowly and relentlessly unravels but nobody cares because everyone is on vacation.

Cognitive dissonance is one thing modern humans are very good at …

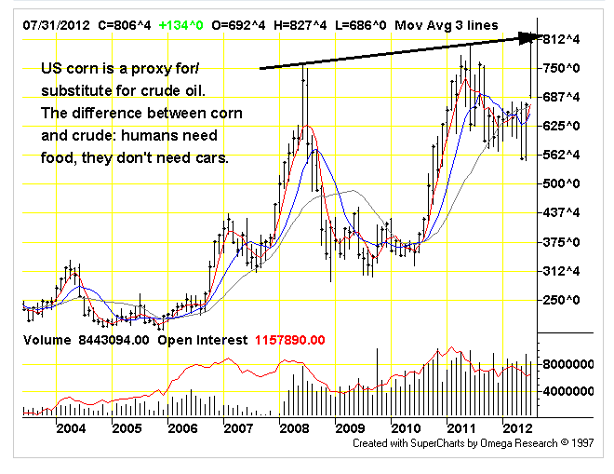

The nationwide drought in the US is having its sport with grain prices, here’s corn (TFC Charts):

Figure 1: the corn market is unique: the foodstuff is also motor fuel. This market is a place where humans can compete directly with both cars and politicians for something to eat.

As in other markets, the overall trend is for higher prices until the affordability limit is reached. Unlike the petroleum market, that limit has not yet been reached. This is fortunate because a diminishing limit would suggest that increasing numbers of our fellow-men are doing without food.

In some ways the food-fuel intersection offers the worst of both worlds: high fuel prices drive food prices by way of corn’s petroleum dependence and its ubiquity in American processed food. If prices are too high there is no switching out of corn into something else.

At the same time, too-high prices of corn have powerful downstream effects on world food markets because corn is a major export crop that overseas consumers rely on as a reserve. Even though US corn is not specifically human food, it is used as livestock feed in countries that are increasing their consumption of meat and dairy products.

The current corn price spike is yet to ripple through the food supply chain. Prices for most processed foods are certain to jump. Food represents a modest percentage of Americans’ income, this is not so overseas. The previous two instances when corn prices were at current levels there were wide-scale food shortages accompanied by droughts. There were grain export embargoes followed by political crises and revolutions. When gasoline is scarce, people stop driving or they drive less until prices decline. When prices are lower they begin driving again. When food is scarce, people don’t stop eating until prices retreat. Food will be bought even if the consequence is ruin, if food cannot be had with money or by way of charity it will be taken by force. The alternative is starvation.

Two components of the current ‘corn crisis’ are a spectacular drought that has centered on the US corn belt along with a government policy that requires motor gasoline to contain a fixed amount of ethanol. Because the corn crop looks to be decimated this year the gasoline requirement is set to absorb a too-large large percentage of the coming crop, leaving minuscule inventories for the upcoming year.

This leaves out that the mandate as it is currently framed will over time absorb the entire US corn crop regardless of its size.

Already, there are calls to eliminate the ethanol mandate. Demand for corn comes from the livestock business which feeds corn to cattle. The shortage of inexpensive corn leaves cattlemen having to slaughter their herds and do so at a significant loss … for the benefit of the automobile industry. Here is the argument, (Wall Street Journal):

This month, four Republican and three Democratic governors asked the Environmental Protection Agency for a waiver of the ethanol mandate, pointing to record prices for corn that are causing sharp rises in the feed costs of livestock producers in their states.“Put simply, ethanol policies have created significantly higher corn prices, tighter supplies and increased volatility,” said Arkansas Gov. Mike Beebe, a Republican, in an Aug. 13 letter to the EPA.

The heretofore silent battle-to-extinction between humans and machines slowly heaves into view. Skirmishes appear in commodities markets in the form of price spikes … for both crude and agriculture goods beginning in 2008. The competition is unfair: machines demand vastly greater amounts of highly concentrated energy than do humans. Machines can be used as collateral for loans, humans cannot. Machine energy requirements are beyond what agriculture — even leveraged industrial agriculture — can provide. Borrowed funds chasing asset yields bid the price of energy sources including corn. The more cars, the greater price pressure on corn and other crops whether there are droughts or not.

When prices are high, because of drought or other reasons, the cars starve the humans who cannot find credit to buy food. Cars are creditworthy, humans are not: the outcome is upheaval, entire countries descend into chaos. Both humans and machines starve, fuel supplies are diverted elsewhere, everyone loses.

The something-for-nothing ethanol fantasy has ‘the productive American farmer’ adding cheap corn to the overall supply of motor fuel, driving down prices at the gas pump. There is no real analysis to support this: ethanol cannot scale. The corn crop of the entire world would not satisfy more than the smallest percentage of US automotive demand. The mandate is a payoff from the government to a favored agricultural constituency: politicians are buying critical corn-state votes whether the mandate makes any sense or not.

High fuel input costs squeeze ethanol producers: ethanol is an expensive, debt-subsidized method of turning natural gas (fertilizers) and diesel fuel into a motor gasoline substitute … in a corn field. The energy return on ethanol production is very low: this can be stated as EROI or EROEI ‘energy return on energy invested’. Ethanol energy return is so low that the industry cannot afford the feedstock if pump prices decline or there is no subsidy. Ethanol production also requires a lot of water to process, something that is hard to come by in a drought.

Fuel consumption ends when prices reach the point where auto use cannot be subsidized with credit flows from other areas of the economy. When fuel prices are too high, fuel is not bought, refiners lose money, less fuel is brought to market. This is the upper bound to the high price of fuel. A long-enough period of non-buying and firms fail: when prices decline the firms do not magically reappear. The outcome is diminishing credit over time, less funds available to subsidize the purchase or use of automobiles and other fuel wasters. The credit upper bound is therefore lower than it might ordinarily appear.

The upper bound on food prices is unrelated to credit. Those feeling the absence of food most sharply do not have ready access to credit, what can be spent for food is a lot less than what the middle classes can afford to borrow then spend on gasoline. Drivers will buy gasoline with credit when citizens nearby have no bread. At the same time, those needing bread will spent what is necessary to gain it until they are made destitute and have no more to spend. The upper bound on food is determined more by limits of societal cohesion and the ability of multitudes to withstand miserable conditions. Relative to the luxury of auto use, the need for food is absolute and so is the upper bound: it is where societies break.

What is underway now has the mechanisms of trade and credit pushing food out of human reach into non-food, motor fuel markets. Most humans are money-poor: they lack credit and have no industrial goods to trade on international markets. The ability of low income persons to produce their own food on their own land shrinks as mechanized agriculture expands. Non-industrial agriculture is forced off the land and farmers into gigantic slums surrounding festering mega-cities. Low income persons’ ability to gain food is put up for grabs in markets that they cannot access. This is another unintended consequence of globalism: agriculture is undermined, populations become more dependent upon food imports.

It is more than charity that requires a decoupling of food and motor fuel. Fuel fantasies must not be allowed to hold food realities hostage. Our fuel situation needs to be taken seriously and ultimately will. This should not occur as a consequence of millions or billions not having enough to eat. Theoretically, a country with sufficient credit could buy the world’s cereal crop then simply hoard or destroy it: a ‘food war’ fought and won on the futures markets. Right now food-fuel competition is a step in this direction: an unhappy trend but perfectly predictable where the (useless) fetishes of modernity are sanctified above all else.

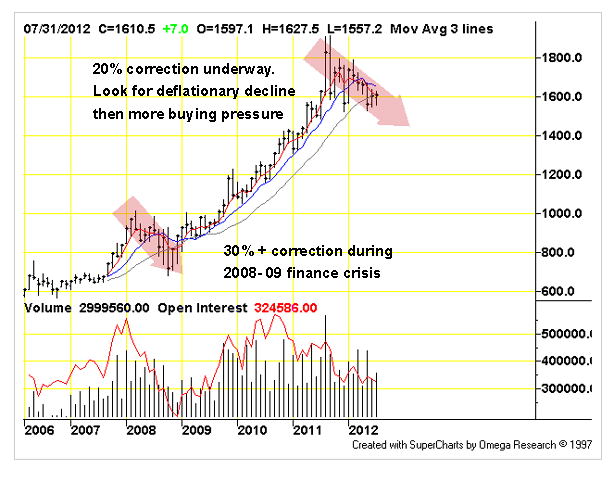

Figure 2: Gold price in a correction: gold prices are subject to leverage used to purchase gold- or gold derivatives. As credit availability diminishes, so does the support for high gold prices … as in all the other markets.

Central banks offer moral hazard, giving finance a green light to lend more funds into the asset markets. A persistent fantasy is the ‘vee-shaped recovery’ that is sure to start tomorrow. This recovery is priced into stock markets: when it is believed by crude oil traders the outcome is the postponement of the vee-shaped recovery as the resulting high crude prices undermine it.

Gold prices reflect uncertainty rather than recovery. Contrary to Internet rumors, inflation is not necessary for a high gold price as buyers can bid the small amount of gold available on the market with funds diverted away from other assets. Deleveraging presses the price of gold downward as it is a collateral asset. Capital flight bids the price upward as money itself is held up to scrutiny and found wanting.

As with the ethanol mandate, none of the architects of the euro ever bothered to analyze the consequences of a member’s failure or that of the Euro-establishment’s credibility. Because all industrial monies are more-or-less identical IOUs, the shaky euro illuminates the vulnerabilities of all the other currencies.

The euro is nothing but claims against bankrupt firms. The dollar along with the others … represents identical claims against identical firms. Humans ‘do’ cognitive dissonance but markets price reality: the fact of an ethanol mandate is by itself suggestive. The US car-centric enterprise — which is the entire US economy and most of the modern world — does not have a foundation of perpetually increasing fuel supply, it has payoffs under the table and wishful thinking.

Gold price increase during a period of deflation is a dangerous sign of capital flight. Gold is an indicator of public trust in the establishment: a way to short it. Rather than rely on shuddering, corrupt institutions, the citizens turn their backs and seek shiny metal talismans, instead.