Baby Boomers! We hardly knew ye …

Where have you gone Joe DiMaggio, the nations turn their lonely eyes to you?

From spastic to sclerotic in a heartbeat.

But it was all good fun, or at least it was supposed to be, chrome-wheeled fuel-injected stepping out over something or other like a corpse on the sidewalk.

Ben Gray, AP Photo/The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

Ben Gray, AP Photo/The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

The boomers are now shuffling off the stage leaving pantloads of trouble behind …

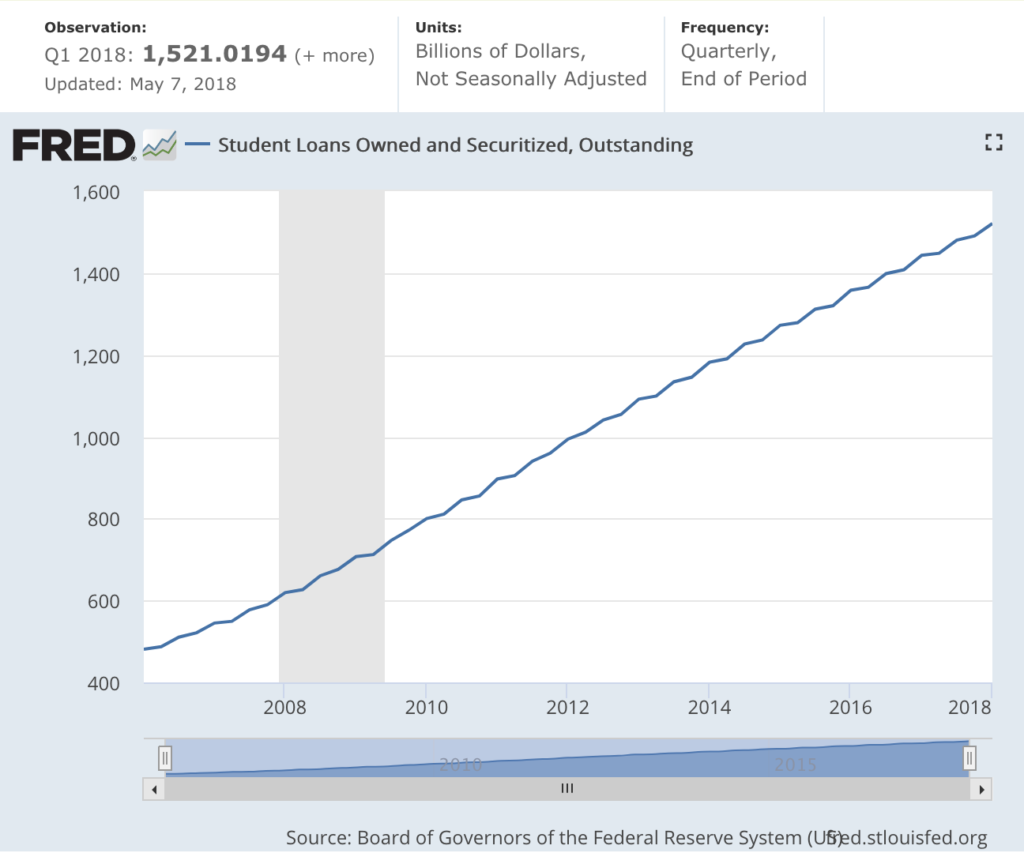

One and a half trillion dollars worth of unpayable student loans, the joke is on who, again?

Men can be distinguished from animals by consciousness, by religion or anything else you like. They themselves begin to distinguish themselves from animals as soon as they begin to produce their means of subsistence, a step which is conditioned by their physical organization. By producing their means of subsistence men are indirectly producing their actual material life.

The 5th of May this year was Karl Marx’ 200th birthday. Besides coming up with a fabulous look, he along with Charles Darwin were the seminal provocateurs of the late-middle Industrial Revolution. Whereas Darwin skewered the creationist affectations at the center of mercantile society — we’re just monkeys after all — Marx took aim at the infrastructure and prime movers of the organization itself. Wrenched by the poverty and distress of 19th century industrial labor and the gilded luxury of the bosses, Marx critiqued society as crass, remorseless, banal, arbitrary and repressive, a mediocre manufactured product no different from the floods of ‘goods’ spat out in torrents from the satanic mills and factories, unmitigated by virtue or invisible hands. Marx was a mirror for what he described: Godless, rational, irreverent and assiduous.

“The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.”

According to Marx, labor creates wealth – surplus value. Business ownership of the financial, manufacturing and distribution infrastructure allows them to capture labor’s value-added surplus for themselves. Business also ‘owns’ the ideological armature (marketing) of the economy so it rationalizes deploying political violence against labor whenever necessary. Technology gives bosses the means to arbitrage the labor-price, pitting each worker against the rest or labor in one place against labor elsewhere. Technology also reinforces the owner advantage by enabling new, fashionable enterprises to undermine the old with ruinous competition; enterprises where labor night otherwise be able to gain advantages of their own.

To the merchants and industrialists, Marx was an irritant who threatened to rile up their workers as well as deter any customers who might have consciences. Alongside Frederick Engels, Marx became synonymous with communism and rebellion, then with a significant form of the great 20th century political innovation, the single party police state. ‘Marxism’ wound up catching the blame for excesses of dictators such as Josef Stalin and Mao Zedong, but what propelled these regimes was not as much Marx or his analysis but the same infrastructure and motive forces that powered industrial capitalism: the advancement of technology; expanding access to resources especially fossil fuels; railroads, steamships, telegraph and telephone, the radio and mass media, machine guns and airplanes, inexpensive broadsheet publishing, the same marketing/propaganda and the Taylorist revolution in business management which made it possible for a small number of bosses to manage in every possible way the entire working lives of tens of thousands of individuals. It was a small jump from dominating the workforce in an industry to entire populations around the clock, to eliminate any distance from working lives to the private lives of individuals no matter how insignificant their role in society.

Marx championed socialism even though he did not invent it. Socialism demands public ownership or control of ‘productive’ infrastructure. It offers workers the chance to gain something more than the choice between wage slavery and destitution. The appeal of socialism tends to increase during money panics and crashes such as the Great Depression or during periods of capitalistic overreach or follies as World War I or the Vietnam War. The appeal wanes during economic booms and ‘gold rushes’, when workers believe they can join the privileged classes, when social equality movements are compromised or outwitted, after periods of active repression; ‘Red Scares’ when socialists are rounded up and sent to prison.

The younger, cosmopolitan boomers were attracted to Marx because he was the ultimate dirty hippie … the bête noire of World War II’s Greatest Generation: those washed out, pallid, gas-guzzling, Negro-hating, Ford Fairlane driving, mac-and-cheese gobbling American suburbanites; he was the hairy, exotic European golem who would slither down the chimney in the middle of the night like a vampire bat and take it all away.

The risk became palpable as technological development offered Moscow the means to annihilate everyone including themselves. The forces of decency were marshaled in the US and unleashed around the world to combat the ‘Red Scare’ (profit from it) wherever it might take root, in Asia, Hollywood and the US State Department. With the opening of China to dollar trade and the collapse of the Soviet Union, the menace that gave Marx his potency evaporated, he was reconfigured into a harmless pop-culture cartoon character, a Warholian ‘bad boy’ in the mold of William Burroughs. Like Warhol himself, but not exactly, Marx become (posthumously) famous, arguably the world’s best known economist … as well as one of the least read …

For what it’s worth, Karl Marx turns out to have been an excellent economist, producing a useful, critical rendering how the commercial economies of his time functioned:

“The bourgeoisie, wherever it has got the upper hand, has put an end to all feudal, patriarchal, idyllic relations. It has pitilessly torn asunder the motley feudal ties that bound man to his “natural superiors”, and has left remaining no other nexus between man and man than naked self-interest, than callous “cash payment”. It has drowned the most heavenly ecstasies of religious fervour, of chivalrous enthusiasm, of philistine sentimentalism, in the icy water of egotistical calculation. It has resolved personal worth into exchange value, and in place of the numberless indefeasible chartered freedoms, has set up that single, unconscionable freedom — Free Trade. In one word, for exploitation, veiled by religious and political illusions, it has substituted naked, shameless, direct, brutal exploitation.”— Communist Manifesto (1848)

If this sounds familiar it should …

Here Marx is rehabilitated … outlines the trajectory of late-stage capitalism and its current existential crisis:

“Anyone reading the (Communist) manifesto today will be surprised to discover a picture of a world much like our own, teetering fearfully on the edge of technological innovation. In the manifesto’s time, it was the steam engine that posed the greatest challenge to the rhythms and routines of feudal life. The peasantry were swept into the cogs and wheels of this machinery and a new class of masters, the factory owners and the merchants, usurped the landed gentry’s control over society. Now, it is artificial intelligence and automation that loom as disruptive threats, promising to sweep away “all fixed, fast-frozen relations”. “Constantly revolutionizing … instruments of production,” the manifesto proclaims, transform “the whole relations of society”, bringing about “constant revolutionizing of production, uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty and agitation”.— Yanos Varoufakis

Marx correctly observed the ‘periodic crises’ were due in part to over-production, inventory excess also shortages of money:

“there are times when it is impossible to sell all commodities, for instance in London and Hamburg during certain stages of the commercial crisis of 1857/58 there were indeed more buyers than sellers of one commodity, i.e., money, and more sellers than buyers as regards all other forms of money, i.e, commodities. The metaphysical equilibrium of purchases and sales is confined to the fact that every purchase is a sale and every sale a purchase, but this gives poor comfort to the possessors of commodities who unable to make a sale cannot accordingly make a purchase either.”

Marx entertained a rational money theory whereby a commodity gains a different, separate character — ‘moneyness’ — when used as a means of exchange. Marx expanded David Ricardo’s labor theory of value; he outlined the loanable funds model, he examined credit and derivatives, described finance as actively expanding business activity rather than being simply warehouses for surplus value; he understood the relation between velocity of money and circulation, the interconnections between institutions (also described by Walter Bagehot in ‘Lombard Street’), the relation between the state and monetary system/central banks, also international finance and ‘world money’. Marx the globalist understood the aim of business was free trade everywhere, and free exchange of capital (money) everywhere.

Marx believed that commercial capitalism would fail due to both a permanent shortage of profit consequent to malinvestment and excess capacity plus managers’ incompetence rendering them useless at managing. Afterward would come socialism, the system whereby workers owned the means of production and kept surplus value for themselves.

Comparing Different Schools of Economics

| CATEGORY | CLASSICAL | NEOCLASSICAL | MARXIST | DEVELOPMENTALIST | AUSTRIAN |

| The economy is made up of … | classes | individuals | classes | no strong views but more focused on classes | individuals |

| Individuals are … | selfish but rationals (but rationality is described in class terms) | selfish and rational | selfish and rational, except for workers fighting for socialism | no strong view | selfish but layered (rational only because of an unquestioning acceptance of tradition |

| The World is … | certain (‘iron laws’) | certain with calculable risk | certain (‘laws of motion’) | uncertain but no strong view | complex and uncertain |

| The most important domain of the economy is … | production | exchange and consumption | production | production | exchange |

| Economies change through … | capital accumulation (investment) | individual choices | class struggle, capital accumulation and technological progress | developments in productive capabilities | individual choices but rooted in tradition |

| Policy recommendations; | free market | free market or interventionism, depending upon the economist’s view on market failures and government failures | socialist revolution and central planning | free market | free market |

This graphic is part of a larger piece from Ha-joon Chang. It offers some of the various disciplines or schools of economic reasoning. Marx’ ideology is compared to others (click to see the larger graph including Debtonomics).

Societies tend not to be the property of specific groups, nor are they easily divided. Instead they are the outcome of billions of us relentlessly re-inventing the world for our own purposes every single day. Production is an abstraction: there is transformation and consumption. All industry is simply a form of consumption; industries’ product is trivia; ultimately waste and entropy: the more effort expended producing more trivia => more entropy produced faster. What drives societies is a kind of defensive self-interest: should an economic actor, firm or individual, fail to act to its own advantage, other actors will take its place. There are no classes, only a gradation or scale upon which the meanest of our species is simply a reduced version of his- or her betters: every worker a robber baron in miniature.

The next part will compare Marx to Debtonomics in more detail.