“Because this is to be asserted in general of men, that they are ungrateful, fickle, false, cowardly, covetous, and as long as you succeed they are yours entirely; they will offer you their blood, property, life, and children, as is said above, when the need is far distant; but when it approaches they turn against you.”— Machiavelli

Marx was a Victorian-era philosopher whose ideology has proven to be remarkably durable. Like Keynes, he was a fierce critic of the status-quo and a fastidious writer: in addition to Communist Manifesto and Capital (with Friedrich Engels), Marx wrote essays about economics, political science and religion, a novel, poetry, a play, articles for various newspapers including the New York Daily Tribune, a torrent of letters, philosophical and mathematical treatises. This was never enough: by the time he died at the age of 64, there was more being made of Marx and his ideas than what he made himself.

This being the true character of genius, and there is much of Marx that can be found in Schumpeter, Michal Kalecki or Hyman Minsky and post-Keynesians; for example, Marx’ observation that economic processes bear within themselves the seeds of self-destruction over the longer term which hints at Minsky’s financial instability hypothesis.

Of the complaints against Marx, two stand out; the first being being the crimes committed by nominally Marxist regimes in the years following World War I, the second being Marx’ advocacy of David Ricardo’s ‘Labor Theory of Value’.

Marx did not invent or endorse the totalitarian single party police state which is essentially a quasi-business cartel that deploys military- and police force. In Marx’ time, ‘rational’ workplace management or Taylorism was part of the process that alienated labor from the means of production, which Marx opposed. Totalitarianism is Taylorism expanded outside the factory to include every aspect of life within the state. Prior governments certainly had tyrannical impulses but the necessary means were not available to give these impulses form. Industry and fossil fuels allowed for large surpluses, technology and management techniques that made the totalitarian regime functional and affordable at the same time.

As the costs associated with these surpluses became burdensome, communistic states either modified themselves to efficiently distribute these costs (China) or else they fell apart (USSR). This permitted Marx’ reputation to emerge from the shadows. Put simply, the labor theory suggests the worth of goods and services depends on the amount- and quality of labor needed to provide them. This seems sensible and does conform to some degree with observation, but critiques of the labor theory began to pop up among economists and others over and over and over and over; the frequency of the complaint is suggestive. Perhaps there is something to the labor theory after all …

Comparing Different Schools of Economics (from Chang)

| CATEGORY | NEO-CLASSICAL | MARXISM | DEBTONOMICS |

| The economy is made up of … | Individuals | classes | a) firms, and b) everything else |

| Individuals are … | selfish and rational | selfish and rational, except for workers fighting for socialism | a) advantage seekers, and b) those being taken advantage of |

| The World is … | certain, with calculable risk | certain (‘laws of motion’) | deterministic and ruthless |

| The most important domain of the economy is … | exchange and consumption | production | borrowing and debt |

| Economies change through … | individual choices | class struggle, capital accumulation and technological progress | resource exhaustion and periodic crashes |

| Policy recommendations; | free market or interventionism, depending upon the economist’s view on market failures and government failures | socialist revolution and central planning | a) restructure, or b) crash, then restructure if possible |

| – | – | – | – |

| Wealth is created by … | innovation and speculation | labor, as residual added value | Wealth is not created but is first made accessible then destroyed |

| Value is … | relational: the utility of a good or service divided by its money cost | the characteristic added to a good or service; social usefulness | solely the characteristic of capital, it does not exist elsewhere |

| Prices are determined by … | marginal utility | labor component of goods and services | marketing, access to credit/creditworthiness of borrowers and lenders |

| Capital is … | human-created means of production including money, infrastructure, intellectual property | money, specifically money intended for speculation | non-renewable natural resources or renewables exploited to the degree they become non-renewing |

Criticism here tends to settle around the difficulty of teasing out a universal labor component from the different varieties of products and services. Marx himself fell into the muddle; in attempting to qualify the labor component he burst it into fragments and contradictions. Yet the labor theory is important. Marx’ revolutionary aims emerge from it: to return wealth to labor where it properly belongs and do so by way of central planning, elimination of private property, graduated taxation, etc. It’s also important because of current controversy over income disparity; returns to labor vs. returns from investment in line with increases in workplace automation, robots and continuing shift of investment funds away from labor: Criticism from economic historian ‘LK’:

John Maynard Keynes, for example, said that Marx’s theories were founded “on a silly mistake of old Mr Ricardo’s” – namely, the labor theory of value. For Michał Kalecki and Joan Robinson the labor theory of value was “metaphysical” (Brus 1977: 59; Robinson 1964: 39), and for Piero Sraffa it was “a purely mystical conception” (Kurz and Salvadori 2010: 199). If the labor theory of value is unsound, then the whole Marxist edifice constructed on it cannot but fall and collapse. Moreover, the classical Marxist idea of historical determinism is also incompatible with the Post Keynesian idea of the fundamental uncertainty of the future.

The future is always uncertain but modernity as it has evolved is no less deterministic: the relentless and annihilating tyranny of progress. Here’s more …

It can be seen that Marx’s argument for the labor theory is a non sequitur. It is not obvious at all that commodity exchanges constitute an equality in the way Marx sees them … It could be that labor value as Marx defines it is non-existent. Marx’s argument was shoddy and commits a straightforward logical fallacy. Later, Marx admits that labor value cannot be completely separated or “abstracted” from use value, so that the whole argument contradicts itself …

The logical fallacy cuts both ways: Marx created a simple model with only a few actors: worker, industrialist, capitalist. According to our critics, if something in the model is non-specific it cannot exist. This leaves economics itself in a bit of a bind as the entire endeavor is itself non-specific and self-contradictory; filled with paradoxes of all kind. The criticism here is reductive and leads nowhere in particular. If labor is non-determinate than what else is? A: “it depends … ” Embedded labor is one component of the cost of any good or service along with capital (inputs), infrastructure and marketing: the most important factor is availability of credit for both the buyer and the seller, who is always more dependent upon credit than the buyer.

The neoclassical answer to the price puzzle is marginal utility (or satisfaction); this is a kind of cop-out, it places marginality in the wrong galaxy in the universe of transactions and suggests the critic is desperate the let the air out of Marx by any means necessary. The creditworthiness of buyers or sellers cannot be teased from the worth of goods nor can speculative interest, which allows the mispricing of anything that can be considered an asset. Labor theory has faults and inner contradictions but no more than any other price discovery regime.

Neo-classical economics can be built around the ‘Transaction Theory of Value’: JW Gilbert (1834) as quoted in Capital observed:

“whatever gives facilities to trade gives facilities to speculation. Trade and speculation are in some cases so nearly allied, that it is impossible to say at what precise point trade ends and speculation begins.”

… the neo-classical transaction theory is a non sequitur … transaction value as conventional economists define it is non-existent, ‘metaphysical’, a ‘purely mystical construction’; the entire argument is shoddy … a straightforward logical fallacy. Labor component is elusive but can be deduced by observing the private equity takedowns of businesses such as Toys ‘Я’ US and cost of resulting layoffs, or headcount reductions due to M&A activities where worth of the labor component is spelled out by management to justify share price increases. Also see, ‘capital-labor ratio’ (Solow)

The better criticism is that Marx did not analyze industrialization to determine whether it offered any returns at all. Like Keynes and the boatloads of ‘Brand X’ economists who came after, Marx presumed industry was productive, based on the mountains of junk spewed from the factories. He then constructed his analysis on that presumption. Marx favored labor over bourgeois speculators and industrialists, he and the rest wanted to keep the industry itself and edit out the ‘bad parts’ by changing management and making other trivial adjustments.

In debtonomics, all individuals are either advantage seekers and those being taken advantage of: as soon as one brigade of rotten managers is overthrown replacements slither out of the woodwork to take their places. Without changing the man there is no changing the management: rottenness can only beget more rottenness.

The actual ‘job’ or purpose of labor in debtonomics is to act as a sink for First Law costs arising from expanding surpluses … This was true in Marx’ time (or Adam Smith’s) as it is now. In debtonomics, labor does not have to ‘produce’ anything (the product of labor is entropy), he/she has only to be underpaid for whatever efforts they might make! That is, the difference between what a worker actually earns and what would be earned under ideal circumstances (labor/productivity parity and competitive workplace) is creamed off to meet surplus management costs wherever they arise, especially debt service. What is The First Law?

The cost of managing any surplus increases along with it until it ultimately exceeds the surplus’ worth.

What is a surplus? It can be anything produced in quantity in nature or by business: coconuts, automobiles, single-family tract houses, foreign currency reserves, debt (particularly), crude oil, leather belts, gold, uranium, dental floss … even workers, surplus managers, baseball players, industry itself! The first-law cost of the surplus of automobiles is traffic, pollution, resource wars, climate change and a million deaths and more annually; the cost of China’s dollar-reserve surplus is the bankruptcy of China. Marx recognized the disruptions associated with industrial production and tsunami of goods; he had only to go a little bit farther toward recognizing costs. He also didn’t recognize the intertemporal mismatch of costs and benefits: costs tend to be permanent while benefits are transient or imaginary.

In Marx, labor and commerce are considered to be irreconcilable adversaries: one class vs. the other. In debtonomics, labor and management, industry and commerce differ only in outline, all of them are categories of consumption; except for certain types of creative workers, labor and the firms that employ them are unable to produce any value at all! The best labor can do is to make capital available by way of their efforts, then destroy it.

Marx’s views on money are not as controversial as his views on (shortchanged) labor: capital is money, but divided as to intentions. ‘Money’ is what people use to buy things, ‘capital’ is money deployed toward returns; it is the means of production, specifically money circulated with the aim of increasing itself:

If we abstract from the material substance of the circulation of commodities, that is, from the exchange of the various use-values, and consider only the economic forms produced by this process of circulation, we find its final result to be money: this final product of the circulation of commodities is the first form in which capital appears.As a matter of history, capital, as opposed to landed property, invariably takes the form at first of money; it appears as moneyed wealth, as the capital of the merchant and of the usurer. But we have no need to refer to the origin of capital in order to discover that the first form of appearance of capital is money. We can see it daily under our very eyes. All new capital, to commence with, comes on the stage, that is, on the market, whether of commodities, labor, or money, even in our days, in the shape of money that by a definite process has to be transformed into capital.

The circulation of money as capital is … an end in itself, for the expansion of value takes place only within this constantly renewed movement. The circulation of capital has therefore no limits.

Marx expanded his money thesis to include credit and the money markets: in ‘Grundrisse’ and in notes that became the 3d volume of ‘Capital’. Here Marx describes the money market, its dangers and the laugh-out-loud schemes and swindles as well as consequences:

The other side of the credit system is connected with the development of money-dealing, which, of course, keeps step under capitalist production with the development of dealing in commodity. We have seen in the preceding part (Chapter 24) how the care of the reserve funds of businessmen, the technical operations of receiving and disbursing money, of international payments, and thus of the bullion trade, are concentrated in the hands of the money-dealers. The other side of the credit system — the management of interest-bearing capital, or money-capital, develops alongside this money-dealing as a special function of the money-dealers. Borrowing and lending money becomes their particular business. They act as middlemen between the actual lender and the borrower of money-capital. Generally speaking, this aspect of the banking business consists of concentrating large amounts of the loanable money-capital in the bankers’ hands, so that, in place of the individual money-lender, the bankers confront the industrial capitalists and commercial capitalists as representatives of all moneylenders. They become the general managers of money-capital. On the other hand by borrowing for the entire world of commerce, they concentrate all the borrowers vis-à-vis all the lenders. A bank represents a centralisation of money-capital, of the lenders, on the one hand, and on the other a centralisation of the borrowers. Its profit is generally made by borrowing at a lower rate of interest than it receives in loaning.

The increase in merchant receipts (bills traded at a discount) represents the expansion of credit …

“The bills of exchange make up “one component part greater in amount than all the rest put together. This enormous superstructure of bills of exchange rests (!) upon the base formed by the amount of bank-notes and gold, and when, by events, this base becomes too much narrowed, its solidity and very existence is endangered. If I estimate the whole currency … and the amount of the liabilities of the Bank and country bankers, payable on demand, I find a sum of £153 million, which, by law, can be converted into gold … and the amount of gold to meet this demand” only £14 million.”

In 1847, the consequence of the rapid and ill-advised expansion of credit was a finance crisis, the trigger was food shortages across Europe. As the crisis revved up, fictitious wealth turned out to be worthless. Marx’ views on money are useful, (Ramaa Vasudevan):

But while a line can be drawn from the banking (credit) school through Marx, to Keynes, Hyman Minsky and the Post-Keynesians, Marx went much further than the banking school in his analysis of the role of money in hoarding and as a means of payment by embedding his analysis in his conception of money as a universal equivalent, even before he addresses monetary circulation and the formation of hoards in the process of reproduction of capital. Critical in his “correction” of the banking school’s argument is the starting point of his analysis in money’s role as a measure of value. His approach illuminates a logical relation between money and credit, but also affirms the contradictory character of this relation by postulating a monetary theory of credit as distinct from a theory of credit-money.

The narrative that runs through industrial economics is increase. Business activity, speculative or otherwise leads to the increase in money-profits leading to the increase in capital leading to more activity, more profits, general expansion, greater complexity, technical innovation, all of this leaving aside disruptions in the cycle, inventory imbalances, money-panics. Marx theorized an increased in capitalization leading to a secular decline of profits, Conventional economics insists on perpetual growth, or if growth winds down take steps to maintain our current lifestyle.

Money becomes in the truest sense a proxy for expansion, the concept of capital (and capitalism) is a three-dimensional narrative myth of human effort to gain something from nothing. Capital expands as money supply increases, but it is never that simple …

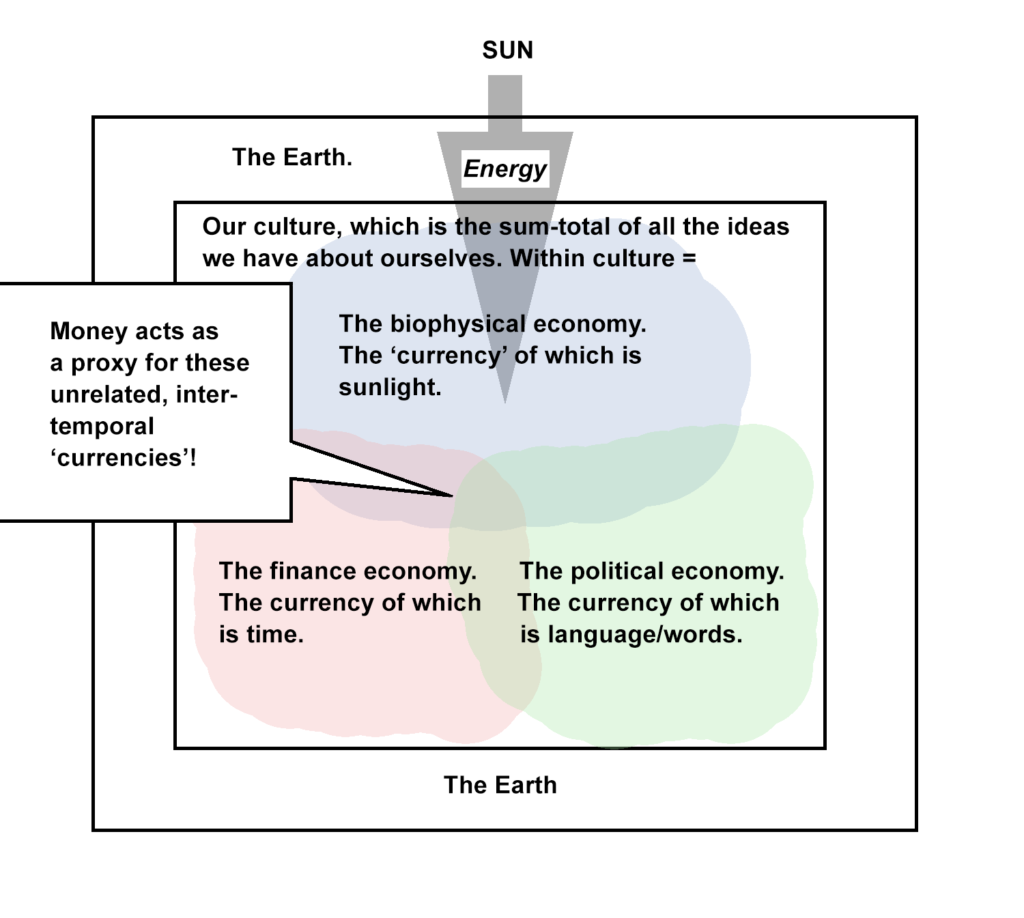

Figure 1: the Debtonomic theory of Money: what is it a proxy for, exactly? It does not matter how much you can buy but rather what you can buy!

We’ve become what we are today because of the ability of our myths to motivate- and direct us. We underestimate our myths’ compulsive power. Our forebears scooted along forest floors picking up- and eating figs. We ate those figs day-after-day for hundreds of thousands of years. We are genetically predisposed to do so; evidence can be seen by looking in a mirror. We have scooting feet, grasping hands and fig-eating mouths. The figs taste delicious to us no matter how many we eat. We are not predators, we don’t have the equipment. Since we aren’t lions or wolves we can only fake it. In the place of DNA sequences we have crafted a defective ideology that misunderstands fundamentals, that proposes a kind of lion that destroys all the other animals. Our myths made us into hunters two million years ago, but only to a point. Our behavior changed but not our natures. We are still fig-eating monkeys, scurrying around, pretending to be gods but falling far short. To become more god-like we must adopt new myths, jettison our bankrupt culture … and learn something new rather than repeat what we already know to be false.