An article in Bloomberg suggests that there will be no recession because indicators are so bad they have no further distance to fall! What sort of logic is this?

Economy Avoids Recession Relapse as Data Can’t Get Much Worse

ByThe U.S. economy is so bad that the chance of avoiding a double dip back into recession may actually be pretty good.

The sectors of the economy that traditionally drive it into recession are already so depressed it’s difficult to see them getting a lot worse, said Ethan Harris, head of developed markets economics research at BofA Merrill Lynch Global Research in New York. Inventories are near record lows in proportion to sales, residential construction is less than half the level of the housing boom and vehicle sales are more than 40 percent below five years ago.

“It doesn’t rule out a recession,” Harris said. “It just makes it less likely than otherwise.”

The possibility of the economy lapsing into another contraction during the next year is 25 percent, he said in a Sept. 1 report. Harris cut his forecast for growth this year by 0.1 percentage point to 2.6 percent and lowered his 2011 estimate by a half point to 1.8 percent, according to the report.

Federal Reserve policy makers agree that a renewed contraction is unlikely, although the risks have risen.

Analysts have convinced themselves that our economy is inherently too dynamic to ‘allow’ anything like a deflationary recession to re- occur:

The Standard & Poor’s 500 Index might increase to about 1,300, while the yield on the 10-year Treasury note would rise toward 4 percent during the next six months or so if the U.S. steers clear of another decline, said James Paulsen, chief investment strategist at Minneapolis-based Wells Capital Management, which manages $342 billion.

Bond Yield

The S&P index closed at 1,080.29 at 4 p.m. yesterday in New York, while the yield on the 10-year Treasury note was 2.58 percent at 4:12 p.m., according to BGCantor Market Data.

“We could have a really violent move,” Paulsen said. “The markets have a lot of double dip priced in,” he added. “I think the idea of that happening is pretty remote.

Inflation, anyone? How the 10yr yield will get to 4 percent without oil prices climbing over $80 is a mystery to me and is unexplained by Mr Paulson – who is presuming a violent move to the upside, right? His ‘cautious optimism’ is echoed by analytic heavy hitters such as Martin Feldstein, Nouriel Roubini, Carmen Reinhart and (ex- Fed governor) Lyle Gramley:

The only double dip in the U.S. since the end of World War II occurred 30 years ago, when the economy turned up in mid-1980 only to fall back into recession a year later. That situation isn’t applicable today, said Gramley, who was at the Fed at the time. The initial decline in 1980 was triggered when President Jimmy Carter imposed credit controls. He quickly reversed himself when the economy collapsed in response.

Postwar recessions traditionally have been prompted by the Fed boosting rates to fight inflation, oil prices rising sharply or businesses suddenly reducing inventories, Gramley said. None of that looks likely this time, he added.

The Fed cut the overnight bank lending rate to close to zero percent in December 2008 and has signaled it intends to keep it there for an extended period.

The central bank “will do all that it can to ensure continuation of the economic recovery,” Bernanke said in his Jackson Hole speech.

Oil prices have fallen as growth has slowed. Crude oil for October delivery settled at $73.91 a barrel yesterday on the New York Mercantile Exchange, down from the 2010 high of $86.84 set on April 6.

Why are some people economic forecasters?

What Gramley doesn’t seem to understand is that a) oil prices have already risen sharply since 1998 and b) what customers can afford to pay as a consequence has declined. Prices can decline and still be unaffordable if worker pay and business income decline faster.

This has been the problem since the great Oil Price Spike in 2008, there is insufficient overall business demand for the economies to proceed: energy prices decline but not enough to allow profitable use (waste) of energy. Oil prices remain ‘cheap’ and decline because no one can afford the higher prices. The same oil is too expensive to allow all- important ‘growth’. Without growth there is insufficient credit formation to bid the price of oil high enough to assure replacement production.

This is the ‘energy compounding spiral’ the fuel equivalent to the debt compounding spiral where the costs of servicing debt compound to the outstanding principal balance with the total expanding exponentially. America and the Eurozone are poised at the edge of this energy- deficit vortex.

Petroleum energy access was not a problem in the US prior to the late 1960’s as this country produced the greatest percentage of the world’s oil. There was more than enough to satisfy domestic consumption with a balance to export. When domestic consumption began to outstrip production US oil companies turned to overseas oil fields. During this post- WWII periods the total amount of petroleum fuel available far exceeded total consumption. Prices were regulated – domestically by the Texas Railroad Commission – so as to keep production from falling onto he markets at a go and obliterating prices.

After the US peak of physical production in 1970 and the government’s abandonment of Bretton- Woods and gold- backing of the US dollar in August, 1971, OPEC decided that the prices set by their US customer were inadequate and the means of payment (paper promises) dubious. In October, 1973, Middle Eastern members of OPEC cut member production 5% with subsequent further cuts in production. Unable to raise prices – set initially by the Texas Railroad Commission, and with other non- OPEC imports restricted by oil company quotas – fuel shortages were widespread across the country. The US nation’s auto fleet of large, low- mileage autos needed quantities of cheap gasoline. The country quickly fell into a severe recession.

Fuel was rationed, first by physical availabilty – shortages – then by fiat: 55mph speed limits and odd- even days for fueling.

The President took the necessary steps to deregulate the petroleum market. From that time until 2008 oil was rationed by price and available credit. Those with access to credit had access to oil, regardless of price. Those without credit were society’s losers who got what they always deserved (who cared whether they could buy oil or not?) At some point the ‘losers’ aggregated to a large enough group to effect overall business demand; this group includes individual consumers as well as companies. The loss of demand has been the cause of the current credit crisis; there is insufficient demand to propel full business production, the lack of production reduces credit availability which feeds back further into employment and demand. It is a deflationary vicious cycle.

The group of society’s losers increases. What ‘grows’ in America is poverty.

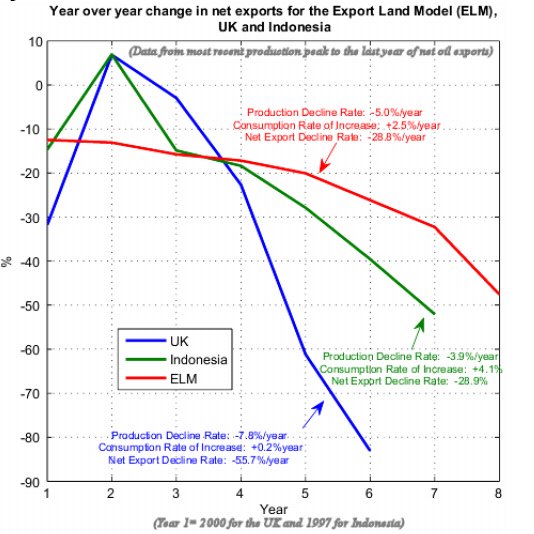

Declining prices constrain production as replacement reserves are much more costly to bring to market than the relatively shallow, dry- land mega- fields of yore. At issue is the decline in replacement production relative to (faster than) the decline in demand. Declines in production due to increased impoverishment of fuel users overall is added to declines in production due to increasing (subsidized) consumption in producing countries resulting in declining exports. This is added to depletion of domestic fields; the cumulative declines are suggestive. Here is a chart from Jeffrey Brown and Sam Foucher illustrating the decline in fuel exports factoring domestic consumption increases:

It isn’t simply one factor or another that weighs on fuel availability but the combination with exacerbating interactions between factors that amplify the overall conditions.

The possibility of debilitating shortages is increasing exponentially. The appearance of voluptuous amounts of fuel ‘on the street’ currently is misleading as low prices will appear to most analysts as constraints in demand rather than demand’s outcome feeding back into the production cycle.

Post- the 2008 price spike the trend in prices has been lower. Credit availability along with demand has collapsed. Here’s an interesting chart from EconomPic to put this in perspective:

As deleveraging continues, fuel will be rationed by physical availability as there will be insufficient business activity to generate the required credit to allow rationing by price. Fuel will be ‘cheap’ but fewer will have the means to afford it. Because of declining cash flow in the production cycle, regions will run out of fuel as was the case in 1973- 74. There will be no replacement without starving another region. The foregoing is both consistent with what has been taking place across the world’s economies to date and is also consistent with deflation.

What has been taking place right under the noses of economists and policy makers!

The declining ability of customers to pay reaches into the future as well. The underlying inflation assumptions are based on extrapolation of commerce growth since the 1940s. Damaged balance personal and business balance sheets dent the nation’s ability to buy and generate credit. More valuable money vanishes from circulation along with inflationary assumptions. It really is different this time!

The energy- compounding spiral will probably emerge as backwardation in the oil futures market: where the price of fuel declines relative to the risk- free price – which includes the cost of ‘carry’ or storage and transfer over time. Currently the oil markets are contangoed – the forward month- contracts are priced higher than the front month – and are presumably somewhat higher than the carry expenses plus interest costs. This would represent a ‘volatility premium’ granted to those who make themselves swing producers, either by having spare capacity in the ground or in floating storage.

Inflationary assumptions die hard. If backwardation appears in the oil markets it will suggest that the forward purchasing power of oil consumers is collapsing. Since much of the world’s purchasing power resides in inflationary hotbeds such as India and China which (presumably) hold large dollar- and foreign currency reserves. Backwardation would be a very strong overall deflationary signal. Can inflation (in one country or area) coexist with deflation? The answers are ‘yes’ and ‘irrelevant’: What matters is value measured in currency. Product material value is arbitrary and capricious. Backwardation in the crude market would indicate that both the money- value of crude and of products derived from crude are falling worthless. It would reinforce the value of currency; priced in (future) oil dollars would become even more valuable.

It also would mean that the emerging countries’ consumption would collapse alongside the US’s and Eurozone. It would be the strongest possible signal to exit long positions in markets and become defensive.

Putting in some water and canned goods might not be a bad idea, either.