Americans since the end of World War Two have for the most part lived with credit expansion and inflation. The components of credit are the same as everything else: supply and demand. Both have been robust as there have been until recently a near-endless parade of ‘innovative’ wasteful enterprises that have been deemed ‘creditworthy’ by the credit manufacturing industry. Consequently, there has been both a bottomless supply of available credit along with those eager to make use of it.

As long as (mispriced) capital could be made available the parade of wasteful enterprises, ‘growth’ and credit expansion could continue. Once capital became scarce, growth ground to a halt to be replaced by ‘shrinkth’. The word for the rest of the 21st century is ‘Less’.

Deleveraging is currently ongoing and the outcome in the industrialized West is general deflation. Moderns have near-zero experience with deflation or appreciation of how it works except in a few countries such as Japan. That country has been able to deflect deflation’s worst effects by way of policy adjustments and a trade surplus: Japan has been able to borrow freely against the accounts of its trading partners.

There are multiple, important, somewhat conflicting dynamics underway right now:

– Debtonomics: credit amplifying or triggering price changes

– Debtonomics: the dollar/crude trade which determines the worth of both.

– Creeping dollar preference and amplified deflation.

– Debtonomics: ongoing collapse of the euro currency as a ‘going concern’.

– Bilateral international trade deals involving crude production that exclude the dollar.

This last is the most important. The current economic establishment is a pop-art ‘masterpiece’ evolved to provide a pseudo-scientific rationale for industrialization and to eliminate credit bottlenecks so that powerful interests have the means to continually expand at the expense of ‘competitors’ and customers. If it appears that the managers don’t know what they are doing it is because they don’t. They’ve never been required to, only to meet public expectations of what managers are supposed to ‘be like’ in the Marilyn Monroe sense.

Both inflation and deflation are matters of credit. Confusion arises because credit is both the cause and effect of price changes. Credit is the enabler of demand, increasing or decreasing it, while at the same time credit is the means by which the demand is satisfied. Access to credit gives the prospective buyer the means to make a bid. Credit also allows the buyer to outbid others then take delivery, the process ‘discovers’ the good’s updated price. In order to meet the new, presumably higher price more credit becomes necessary along with more credit-worthy buyers. These appear because the new price represents an increase in similar items’ worth as collateral.

Because of universally available credit over the span of decades there is no such thing as a ‘fundamental’ price. Leverage is the largest component of the market price of pretty much every good: prices tend to be wildly inflated. Nobody knows what anything is really worth. Confusion over worth is another component of our interlocking set of paralyzing crises. Due to the buildup of leverage, within every transaction lies the possibility of fatally over-paying for a good: making a purchase an instant prior to an unstoppable cascade of deleveraging or in some way triggering it.

During and after the long period of credit expansion, the purchase of any good requires over-paying for it. One either over-pays or declines to bid. Credit begins to contract when the market is cleared of buyers, after the last person seeking entry into a market has bought in. At that point, all are sellers looking either for an opportunity to exit or are anxious for events to hound them out of the market at a thumping loss. Because of the length of the just-ended credit expansion, the fundamental- or cash-price of just about every good is substantially lower than the current — unstable — credit price: this includes petroleum.

The price of a house is its mortgage price, that is the cash worth of the house added to the effect of the mortgage that must be taken on to buy the house. This mortgage price becomes that of all the other houses whether a mortgage is taken on or not. The universally available mortgage amplifies what customers can pay for all houses … for all college educations and hospital stays, for jet fighter planes and SUVs, for guided missile cruisers, for exchange-listed companies and everything else under the sun. Whatever can be afforded by way of a torturous scaffold of credit becomes the collateral basis for succeeding rounds of credit.

A house might be worth twenty-five thousand dollars in cash as that is the equity that can reasonably be demanded to secure the mortgage. Mortgage availability determines equity by way of the ‘back door’: the price of the same house would be five hundred thousand dollars because this is what the equity plus the mortgage will support.

Likewise, the crude oil futures market is a ‘margin’ or leverage market as the price includes the margin needed to buy the fuel contract: the margin is bought along with the fuel itself. Without leverage in the fuel markets — and in the pockets of customers — the cash price of crude oil would be very low, perhaps $5 or $10 per barrel. The additional $100 in the form of credit is assumed to always be available to market participants.

Times have changed. The vast quantities of low-priced fuel once available when it last cost $10 per barrel have long ago been spent into the atmosphere as waste. Ours will not be great-grandfather’s $10 fuel or even the 1998 variety. Instead of the low price representing an increasing surplus, it will represent the annihilation of demand.

The credit stripped from fuel would have credit stripped from everything else, including wages, investments and other sources of income.

Credit represents multiple parallel forces under tension, it is at odds with itself. Credit interferes with market price discovery function. Non-linearities and feedback loops are inherent to the credit function and the accompanying accumulation of debt. Many of these non-linearities are difficult to perceive against the background of ‘market noise’ and the generalized assumption of credit expansion.

Credit is made available by virtue of fuel waste enterprises that are considered as something other than fuel waste enterprises. If these were ever honestly considered no credit would ever be extended to them.

Our fuel wasting enterprises are worth much less than their current market prices. The enterprises have diminishing worth as collateral, regardless of what the promoters claim and what assumptions support. Even at the lowest price, fuel has far greater worth than what can be gained by wasting it for nothing. Here is your ‘Great Arbitrage’, between the worth of enterprises’ capital inputs and the worthlessness of the enterprises themselves! Everything is worth more than zero. At the same time, the waste of past decades has left the world nearly empty of value. Waste is promoted within pop-culture as a metaphysical journey or transformation leading toward a socially and personally gratifying future where values will presumably reappear by magic. The arrival of this precious future is vague, in fact it is the ultimate “I’ll pay you on Tuesday” fraud. Waste is nothing more than the means to borrowed profits for enterprise owners, the costs being shifted onto the suckers who happen to be these same enterprises’ customers.

Both fuel and house prices are relative. They are the children of credit, determined by credit creation in fuel- and house markets. The ability to pay is also a creature of the same markets but at a lower level. Ability to pay decreases faster than do prices because the (credit) price of wages/earnings is arbitraged against the (credit) price of goods and services. Credit arbitrage straddles the different markets, between costs and what can meet them, what the waste-dependent businesses need to survive and what customers can afford to borrow.

The price of fuel is high relative to the ability of users to pay for it. Even a deflated price is a high price.

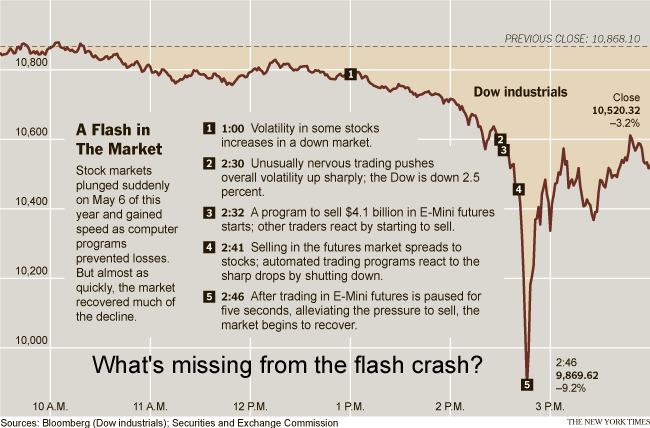

The margin- or credit price of fuel will always be too high, whoever pays for it is over-paying. The price discovery mechanism is not only at hand but is wound like a spring needing practically nothing to set it into motion (Barry Rithotz and Bloomberg)(Click on for big):

Figure 1: What’s missing from the flash crash? A marching band: here is the same index for sale in two different markets with trade arbitraged between the two. An identical form of index arbitrage took place in October, 1987. Had the arbitrage expanded outside of the stock exchange machinery in May the index would have flash-crashed all the way to the non-credit price. What propels deflationary arbitrage is the same thing that propels its inflationary counterpart: price discovery across multiple marketplaces. In this flash crash, the deflationary process strips credit rather than enabling it.

The effects of relatively expensive fuel is something to pay attention to. In 2008, the too high price was over $140 per barrel. Now, the too high price is near to the current $120 per barrel. In a few months more the too high price will be less than $110 which is a severe problems as the cost to produce is at $100 per barrel or more. At some point there will be physical shortages as ‘expensive’ production is shut in or left undeveloped.

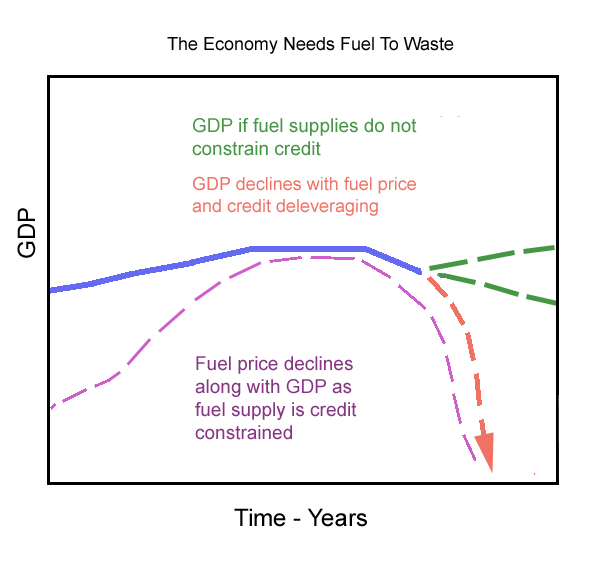

Figure 2: Flash crash in the material world: a schematic of GDP (in blue) and fuel price (violet). Red represents GDP linked to the (diminishing) creditworthiness of waste-based enterprises. Deleveraging cuts fuel supplies which in turn causes GDP to collapse which delevers fuel prices. Fuel prices and output can be arbitraged with losses in one amplifying losses in the other then back again.

Energy deflation accelerates as fuel shortages silence the machines. The fuel price of the moment is then too high. This high price results in yet more demand destruction which takes place even as fuel production decreases. To the producers there is a perceived surplus of fuel which requires cutting supply. To the consumers who waste fuel, the price is always too high requiring cuts in demand!

During deleveraging periods, declines in supply have an out-sized adverse effect on demand. The decline in demand outstrips any decline in production. Because of this accelerating imbalance, just about any price is too high.

Conventional analysis suggests that fuel shortages will result in higher prices. This assumes there are reserves of ‘excess’ cash savings or credit available or that shortages will magically provide more credit. A fuel shortage will cause credit to disappear; the fuel price will decline while the discretionary purchasing power of customers declines faster.

The imbalance between supply and demand indicates fuel might suggest a higher per-barrel cost. If fuel prices cannot increase, the amount of increase will be subtracted instead from the purchasing power of customers. This will appear as a decline in the ‘C’ or consumption component of Keynes’ famous GDP equation.

This vanishing purchasing power would then ‘de-lever’ backwards through the fractional lending system. What would be stranded is not simply the credit embedded within fuel-specific goods but credit leveraged to the multiplier which is embedded within all goods and services, wages and investment returns. This deleveraging would take place (and is currently underway in Europe) until the fuel price declines to a level affordable to a regime that is completely stripped of credit!

Our high fuel prices are causing fuel-driven deflation by removing purchasing power from economies. You drive a car or you have money in your pocket but not both at the same time: that is your choice for 2012.