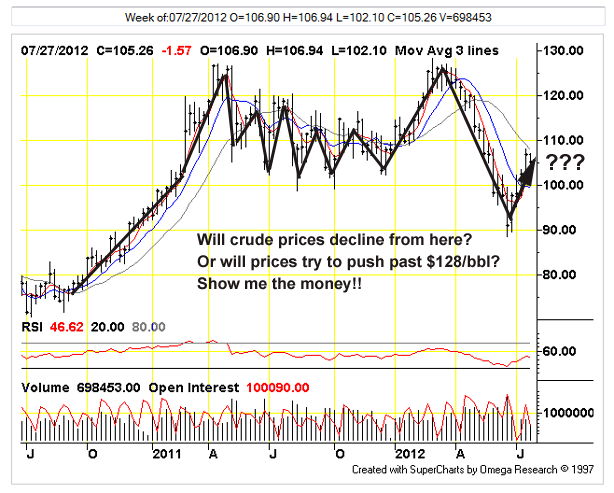

Figure 1: Petroleum prices rebounded $15 per barrel over fears of more warfare in the Middle East (Chart by TFC Charts, click on for big). Spare bags of money are presumably set aside for periods when petroleum is in short supply. The refiners — which buy all crude petroleum with a mind to sell it in other forms to (broke) customers for a profit — are expected to reach for this cash whatever petroleum is scarce and pay whatever price is necessary to get the crude they need. Enter the bags of money: public be damned!

Reality is more complex: any competition for supply requires more credit which pushes prices higher. Availability of credit and willing borrowers (not a given) is the variable. Those with the credit can meet the price, those without don’t. At some point, both fuel and credit become unaffordable: this in turn pulls the plug on prices. This dynamic is the cause of the price movement seen on Figure 1.

What is underway around the world — particularly in Europe — is unaffordable credit and an accompanying decrease in the rate of credit creation. This trend is not favorable for bullish crude oil speculators or producers which need high prices to meet (increasing) demand at exponentially increased cost.

Professor Steve Keen had the following over on his web site:

The Crisis in 1000 words—or less

URPE–The Union for Radical Political Economics–is holding a Summer School for the Occupy movement, and as part of that invited papers that explained the crisis in 1000 words or less (so that they can be printed on one double-sided sheet). Here’s my effort in somewhat less than 1,000 words (though with 2 figures). In the interests of URPE’s objective in this exercise, here’s the PDF of this blog post for general download.

Looking over the URPE’s site there is nothing to seen about 1,000 words or even 2,500 words which is par for the Undertow. Nevertheless, a synopsis of the general economic tenor with a brief set of useful approaches might be positive. Of course, the risk is being excluded from a union of radicals for being too radical.

Toil has produced the requisite 1000 words and time will tell whether it will appear @ URPE or not. If not I will post it here (I will post it here, regardless). Here are Professor Keen’s 1000 words:

Steve Keen (Debt Deflation)

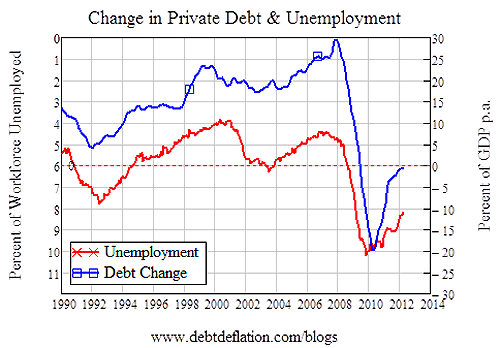

Both the crisis and the apparent boom before it were caused by the change in private debt. Rising aggregate private debt adds to demand, and falling debt subtracts from it. This point is vehemently denied on conventional theoretical grounds by economists like Paul Krugman, but it is obvious in the empirical data. The crisis itself began in 2008, precisely when the growth of private debt plunged from its peak of almost 30% of GDP p.a. down to its depth of minus 20% in 2010. The recovery, such as it was, began when the rate of decline of debt slowed. Across recession, boom and bust between 1990 and 2012, the correlation between the annual change in private debt and the unemployment rate was -0.92.

The causation behind this correlation is that money is created “endogenously” when the banking sector creates loans, and this newly created money adds to aggregate demand—as argued by non-orthodox economists from Schumpeter through to Minsky. When this debt finances genuine investment, it is a necessary part of a growing capitalist economy, it grows but shows no trend relative to GDP, and leads to modest profits by the financial sector. But when it finances speculation on asset prices, it grows faster than GDP, leads obscene profits by the financial sector and generates Ponzi Schemes which are to sustainable economic growth as cancer is to biological growth.

When those Ponzi Schemes unravel, the rate of growth of debt collapses and the boost to demand from rising debt becomes a drag on demand as debt falls. In all other post-WWII downturns, growth resumed when debt began to rise relative to GDP once more. However the bubble we have just been through has pushed debt levels past anything in recorded history, triggering a deleveraging process that is the hallmark of a Depression.

The last Depression saw debt levels fall from 240% to 45% of GDP over a 13 year period, and the ensuing period of low debt led to the longest boom in America’s history. We commenced deleveraging from 303% of GDP. After 3 years it is still 10% higher than the peak reached during the Great Depression. On current trends it will take till 2027 to bring the level back to that which applied in the early 1970s, when America had already exited what Minsky described as the “robust financial society” that underpinned the Golden Age that ended in 1966.

While we delever, investment by American corporations will be timid, and economic growth will be faltering at best. The stimulus imparted by government deficits will attenuate the downturn—and the much larger scale of government spending now than in the 1930s explains why this far greater deleveraging process has not led to as severe a Depression—but deficits alone will not be enough. If America is to avoid two “lost decades”, the level of private debt has to be reduced by deliberate cancellation, as well as by the slow processes of deleveraging and bankruptcy.

In ancient times, this was done by a Jubilee, but the securitization of debt since the 1980s has complicated this enormously. Whereas only the moneylenders lost under an ancient Jubilee, debt cancellation today would bankrupt many pension funds, municipalities and the like who purchased securitized debt instruments from banks. I have therefore proposed that a ‘Modern Debt Jubilee’ should take the form of ‘Quantitative Easing for the Public’: monetary injections by the Federal Reserve not into the reserve accounts of banks, but into the bank accounts of the public—but on condition that its first function must be to pay debts down. This would reduce debt directly, but not advantage debtors over savers, and would reduce the profitability of the financial sector while not affecting its solvency.

Without a policy of this nature, America is destined to spend up to two decades learning the truth of Michael Hudson’s simple aphorism that “Debts that can’t be repaid, won’t be repaid”.

Start here:

… money is created “endogenously” when the banking sector creates loans, and this newly created money adds to aggregate demand—as argued by non-orthodox economists from Schumpeter through to Minsky. When this debt finances genuine investment …

Here are two assumptions: that industrialization is a permanent condition and that industrial enterprises are productive (genuine investment). Both assumptions are false: gravity is a permanent condition, industries are fads like petticoats, mullets and disco. Industrial businesses don’t pay their own way, if they could do so they would have done so already.

Rather, industries are born into debt and there they remain until they fail or are absorbed into larger industries and agglomerations of debt. What we consider ‘growth’ and ‘progress’ has been the expansion of world’s balance sheets over a period of centuries. It’s been around so long we’ve gotten accustomed to it.

Meanwhile, the increase in debt is described by Minsky and Keen to be a speculators’ project rather than the ongoing enabler of industrialization. Minsky: debt is taken on to produce goods and services first. The next stage is an expansion of speculative borrowing to produce money returns on marginally productive enterprises. At the end of the credit cycle, hedging speculators erect Ponzi schemes that rely on the expansion of debt to provide returns. At some point the absence of real returns ends the credit cycle and deleveraging takes hold.

In debtonomics: the first rounds of debt bring firms into being and provide cash flow to maintain them (debt taken on by the firm’s customers, the state or by way of foreign exchange). The next rounds of debt are taken on to refinance the first rounds and provide (large) profits for the entrepreneurs. Succeeding rounds of debt are taken on to finance the preceding rounds: at some point new debts finance existing debt and nothing more.

In both models, credit is endogenous, the product of private finance for its own purposes.

Here is when the cost of an expanding surplus — credit — is overtaken by the expanding costs of managing that surplus. The (Steve’s) First Law of Economics states the costs of managing any surplus increase along with the surplus until they exceed it. Even as credit is structured so that borrowers’ interest costs decline with the increased size of the loans, the associated costs of surplus emerge elsewhere. In our instance they take the form of pyramiding ‘dead money’ debts that are hopelessly unpayable!

Keen and Minsky imply the First Law without addressing it as such: this is because Ponzi financing, the last phase of Minskian credit expansion is a cost.

Keen:

If America is to avoid two “lost decades”, the level of private debt has to be reduced by deliberate cancellation, as well as by the slow processes of deleveraging and bankruptcy.In ancient times, this was done by a Jubilee, but the securitization of debt since the 1980s has complicated this enormously. Whereas only the moneylenders lost under an ancient Jubilee, debt cancellation today would bankrupt many pension funds, municipalities and the like who purchased securitized debt instruments from banks. I have therefore proposed that a “Modern Debt Jubilee” should take the form of “Quantitative Easing for the Public”: monetary injections by the Federal Reserve not into the reserve accounts of banks, but into the bank accounts of the public—but on condition that its first function must be to pay debts down. This would reduce debt directly, but not advantage debtors over savers …

Easy to say (and unfair): when the establishment can ‘print’ crude oil or other forms of capital, at that point debt forgiveness can be taken seriously’ (replacement of a virtual good by the real thing.

The problem that Keen seeks to solve is the Debt = Wealth conundrum. Eliminating debt eliminates an equal amount of wealth. All economic accounting entities exist in two reference planes at the same time. That is, every asset is another’s liability and vice-versa. Nothing within the economy is un-owned, no funds exist outside of the economy. The spare bags of money set aside for periods when petroleum is in short supply do not exist. Money/credit in one’s possession must be removed from another, or it is lent into existence with the funds lodged against equal liabilities. In this sense, accounting entities are never created new or destroyed, custody of these entities is passed back and forth between agents.

Central bank funds are not ‘new money’ in the sense that they do not exist before the bank lends them into existence. Funds find their way to the bank from private sector balance sheets where they gain new form but not substance. The central bank balance sheet expands as the private sector’s shrinks. For this to be otherwise the central bank would be insolvent, no different from its insolvent banker-clients.

Injections by central banks are loans. By offering loans to the public Keen suggests that those with debt would repay theirs (deleveraging) while those with no debts would obtain a bonus for being thrifty. This would prevent the thrifty from going postal when deadbeats are taken off the hook (debt) while savers are not compensated in any way (wealth).

The beneficiaries are the commercial banks that made the (bad) loans in the first place. Funds in question would flow to the them whether the citizen-beneficiaries are indebted or not (to both sides of the same banks’ balance sheets).

– If the citizens are indebted they gain no real benefit: the lenders’ credit exposure is passed to the central bank.

– If citizens are not indebted, credit again flows to the banks in the form of liabilities (deposits are banks’ liabilities, unsecured loans by the public to the banks). In order to gain any benefit, the depositor would be required to ‘defeat the system’ which leverages itself against the deposits.

In both instances the customers would be conduits for a bailout: from the central bank => to the public => to the commercial banks => (back to the central bank).

Insolvency would shift from the indebted public => to the commercial banks => to the central bank => back to the public through the back door. The guarantor of central banks’ liabilities is the same public Keen seeks to relieve, the public is writing checks to itself with banks as intermediaries.

Bank deposits would be hypothecated to the central bank as collateral for leveraged loans to the commercial banks on one hand, back to depositors on the other. Welcome to the Twilight Zone!

The central bank cannot offer unsecured loans or create new ‘money’ or leverage itself. Doing so risks the central bank becoming insolvent for the same reason as the other banks. The reason for a Jubilee in the first place is leverage and insolvency. Once the central bank leverages its balance sheet there is no real lender of last resort. The outcome is a system-wide bank run, as is underway in Europe for just this reason.

Any loan by a central bank must be secured by collateral which the general public is unable to offer. Loans made to/by a bank are commodities to third parties, not to the banks’ customers. The public cannot offer collateral other than their deposits, the banks do in their place without any public input in the process. Keen offers deposits as collateral to the central bank because there is no other collateral to be had. Banks’ assets (loans to customers) are non-performing and are not good collateral. Deposits would become collateral for leveraged loans made back to the depositor. Deposits would effectively become bank equity, subject to bankruptcy and margin calls. As with LTRO in the EU, depositors would be subordinated to all other claimants against the bank.

The only way for depositors to escape leverage/subordination is to remove their deposits from the system. Tres bank run!

The Jubilee represents ‘dead money’ debts, taken on to refinance existing debts.

The alternative is for the government — not the central bank — to issue fiat currency (greenbacks) in amounts equal to maturing debt. The debt is retired, the currency issued for the purpose is extinguished. There are risks to the debt-money system which exists with difficulty where the public can issue currency at will.