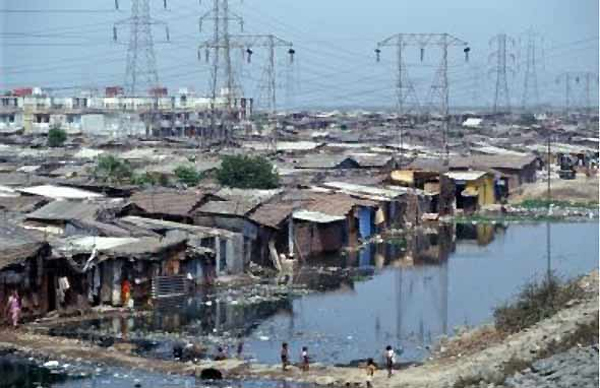

Nicole Foss — Stoneleigh — recently published an article about the recent electric blackout in India where hundreds of millions lost power. The article is very comprehensive and well worth the time to read it. As informative as the article are some of the photographs;

A slum is a favela is a shanty-town. Here is a typical slum in India/anywhere in the world (unknown photographer). The canal in the foreground is both sewer and source of drinking/washing water. Life in this slum is brutish, nasty and short. How can it be otherwise?

Slums are a product of modernity just the same as automobiles and jet airplanes. They are economically segregated areas, places where society’s losers are swept. Modernity washes its hands of the slum-dwellers then moves onto other business … the creation of more slum dwellers. Slums are the end product of social Darwinism, the necessary ‘yin’ to business success ‘yang’.

More success = more slums. Failure of the process also = more slums. Modernity asserts that it eliminates poverty. Slums stand as evidence that modernity creates poverty. More modernity = more poverty.

Anywhere from 800 million to 2 billion of the world’s citizens live in shanty-towns, many within/surrounding sprawling modern mega-cities. A few older slums are stable, their inhabitants are transforming these places into functional urban neighborhoods with land title, utility services and permanent structures. Most slums are temporary pop-up collections of plastic trash and worn packaging materials, that only last until the landowner, flood or other disaster wipes them away.

Creating neighborhoods is something humans have done for thousands of years, are generally good at it. Third-world slums are city building on a human scale: they are non-automobile habitats. In this sense they represent both humanity’s past and future.

Slums appear where there are people desperate for housing, where a piece of land can be occupied at little- or no cost. Often these are industrial spoil dumps or city garbage pits, border-area refugee camps, abandoned- or contested development sites. Some slums are a single building or collection of older, obsolete structures.

Ad-hoc landlords divide the space into shack-sized lots or ‘rooms’ that are rented for pennies per day to the poorest of the poor. Because slums are ‘unofficial’ there are generally no services other than the odd street light and perhaps a water tap. One tap may be the only source of clean water for five thousand- or more people. Many slums have no clean water supply at all and require trips by residents to distant wells or periodic visits by (expensive) water trucks. There are scarce- or no toilets or sewers, few rules, no police or government authority, no medical care. There are improvised micro-economies of interrelated small businesses many of which are tinkers’ trades. Like the slum itself, its economy is both anti- and postmodern. Interface with ‘regular’ finance and industry takes place at the margins of the slum.

Because slums are not automobile habitats they can be confused by some with traditional city developments that emerged before the auto-industrial period. The ‘traditional city’ has high density human dwellings and small businesses with all areas accessible on foot. This kind of development is also refined: inhabitants are prosperous, there are excellent services available.

Mallorca street (Nathan Lewis) This is an economically segregated area but cannot be considered a slum. It shares many of the physical characteristics of one: narrow streets, buildings up against the street, the absence of a central ‘plan’ or developer. Narrow streets allow more living space in a given area. At one time this village might have have been a slum, if this is so these beginnings were left behind once original shacks were replaced with permanent structures and the owners given property rights.

Stewart Brand believes slums have something to offer: they are ‘efficient’:

How Slums Can Save The Planet

In 1983, architect Peter Calthorpe gave up on San Francisco, where he had tried and failed to organise neighbourhood communities, and moved to a houseboat in Sausalito, a town on the San Francisco Bay. He ended up on South 40 Dock, where I also live, part of a community of 400 houseboats and a place with the densest housing in California. Without trying, it was an intense, proud community, in which no one locked their doors. Calthorpe looked for the element of design magic that made it work, and concluded it was the dock itself and the density. Everyone who lived in the houseboats on South 40 Dock passed each other on foot daily, trundling to and from the parking lot on shore. All the residents knew each other’s faces and voices and cats. It was a community, Calthorpe decided, because it was walkable.

Building on that insight, Calthorpe became one of the founders of the new urbanism, along with Andrés Duany, Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk and others. In 1985 he introduced the concept of walkability in “Redefining Cities,” an article in the Whole Earth Review, an American counterculture magazine that focused on technology, community building and the environment. Since then, new urbanism has become the dominant force in city planning, promoting high density, mixed use, walkability, mass transit, eclectic design and regionalism. It drew one of its main ideas from the houseboat community.

How precious: Calthorpe “introduced the concept of walkability in “Redefining Cities.” What did people do before marketing? People have been walking in cities for as long as cities have existed. People live in slums because they cannot afford to live elsewhere, not because they are walkable. Persons with sufficient incomes exit their slums without hesitation. There is no upside to living in squalor, no matter how much the concept is ‘redefined’.

Every year millions are swept out of the countryside by agricultural colonialism and industrial expansion. There are insufficient opportunities in rural communities to employ displaced agricultural workers. A lure of the cities is factory jobs, both in- and outside of urban sweatshops: labor migrates toward income as it has since the dawn of mankind, it also goes where it must.

There are plenty more ideas to be discovered in the squatter cities of the developing world, the conurbations made up of people who do not legally occupy the land they live on—more commonly known as slums. One billion people live in these cities and, according to the UN, this number will double in the next 25 years. There are thousands of them and their mainly young populations test out new ideas unfettered by law or tradition. Alleyways in squatter cities, for example, are a dense interplay of retail and services—one-chair barbershops and three-seat bars interspersed with the clothes racks and fruit tables. One proposal is to use these as a model for shopping areas. “Allow the informal sector to take over downtown areas after 6pm,” suggests Jaime Lerner, the former mayor of Curitiba, Brazil. “That will inject life into the city.”

The informal sector in slums is drug dealing, robbery and kidnapping, punctuated with battles fought with automatic weapons between gangsters and the police.

The reversal of opinion about fast-growing cities (slums), previously considered bad news, began with The Challenge of Slums, a 2003 UN-Habitat report. The book’s optimism derived from its groundbreaking fieldwork: 37 case studies in slums worldwide. Instead of just compiling numbers and filtering them through theory, researchers hung out in the slums and talked to people. They came back with an unexpected observation: “Cities are so much more successful in promoting new forms of income generation, and it is so much cheaper to provide services in urban areas, that some experts have actually suggested that the only realistic poverty reduction strategy is to get as many people as possible to move to the city.”The magic of squatter cities is that they are improved steadily and gradually by their residents. To a planner’s eye, these cities look chaotic. I trained as a biologist and to my eye, they look organic. Squatter cities are also unexpectedly green. They have maximum density—1m people per square mile in some areas of Mumbai—and have minimum energy and material use. People get around by foot, bicycle, rickshaw, or the universal shared taxi.

Not everything is efficient in the slums, though. In the Brazilian favelas where electricity is stolen and therefore free, people leave their lights on all day. But in most slums recycling is literally a way of life. The Dharavi slum in Mumbai has 400 recycling units and 30,000 ragpickers. Six thousand tons of rubbish are sorted every day. In 2007, the Economist reported that in Vietnam and Mozambique, “Waves of gleaners sift the sweepings of Hanoi’s streets, just as Mozambiquan children pick over the rubbish of Maputo’s main tip. Every city in Asia and Latin America has an industry based on gathering up old cardboard boxes.”

Slums carry with them the constant risk of displacement, generally slum dwellers have no property rights. It is difficult for those with small means to divert some of them toward improving places they have little or no interest in.

Life in the slums is anchored in modernity, consumer demand is taken wherever it can be found:

Life In The World’s Slums

In Bangkok’s slums, most homes have a colour television—the average number is 1.6 per household. Almost all have fridges, and two-thirds have a CD player, washing machine and a mobile phone. Half of them have a home telephone, video player and motorcycle. (From research for UN report The Challenge of Slums.)

Residents of Rio’s favelas are more likely to have computers and microwaves than the city’s middle classes (Janice Perlman, author of The Myth of Marginality.)

In the slums of Medellín, Colombia, people raise pigs on the third-floor roofs and grow vegetables in used bleach bottles hung from windowsills. (Ethan Zuckerman, Berkman Center for Internet and Society at Harvard Law School.)

The 4bn people at the base of the economic pyramid—all those with [annual] incomes below $3,000 in local purchasing power—live in relative poverty. Their incomes… are less than $3.35 a day in Brazil, $2.11 in China, $1.89 in Ghana, and $1.56 in India. Yet they have substantial purchasing power… [and] constitute a $5 trillion global consumer market.

Population growth gallops ahead of the ability of development to deliver anything more than cheap, energy gobbling consumer goods. These give the illusion of ‘progress’ while inflation suggests that the poor are earning more money when in real terms they aren’t.

It’s hard to compare life in a medieval European village or a yacht harbor in the San Francisco Bay area with living in a shanty town in Bangkok, Mumbai or elsewhere in this world:

Paul FennI unintentionally found myself living (flat broke at 34 years old) in a slum off Jalan Wahid Hasyim in downtown Jakarta in ’94 for two months. It was the most disgusting, scary, dark, bleak, psycho, messed up two months a person could have. I’m talking about swarms of dengue-infected mosquitoes from dusk till dawn, cockroaches slapping off the walls like flying moccasins nightly, bloated ticks on the walls, intense heat and 100% humidity always, an auto body shop that started banging hammers on car panels at 6am 7 days a week, a mosque on each side of our house, complete with blown-out speakers calling locals to prayer 5 times daily, a disco behind us thumping on till 7am every morning, rats, dogs, cats all of them wild, mangy, diseased, flea-and-tick-bitten, puking and hunger-crazed, regular power failures, single-mom hookers lurking, screaming, pot banging food vendors day and night, storm-triggered floods of black, stinking filth, the toxic stench of burning plastic and vegetation always. And that was just down the alley I lived on.

Walk out into the streets and it was thousands on thousands of cars, trucks, motorbikes, buses and two-stroke Indian-made Bajai taxis all jammed up, barely moving, all churning out black and blue smoke. Fold in rotting, burning garbage piled randomly with no hope of ever being collected, missing sidewalk covers over canals filled with what looked like black snot and choked with a billion plastic bags, coconuts, palm fronds, trees and Christ knows what else, plus disfigured, heartbreakingly filthy beggars here and there, the sick and aged homeless selling their trifles to make ends meet, corruption from the parking mafia on up to the president… and this wasn’t the city’s worst slum. Though I went there too and saw people bathing babies and brushing teeth in rivers you wouldn’t dare throw a lit match into.

Sorry, Mr. Brand. This is the most insane, out-of-touch pile of white-guilt-assuaging crap I’ve come across in decades. You have no idea what you are talking about, sir. Stay aboard your yacht in Marin where you’ll be safe in your delusions. I’ve also spent time on a yacht in your marina, and can tell you that that life couldn’t be any further removed from the reality of slum living, unless you moved it to the moon.

People in the slums hate their lives (no matter how much they may smile at you as you pass by in your Indiana Jones hat and cargo pants full of candies for their kids), and for thousands of sound reasons. There is nothing happy or applicable to be pulled out of slums other than the knowledge that they are cesspools of tragedy, misguided dreams, unimaginable filth and evil.

In slums there are no regular sources of power. Instead, there are jury-rig connections to the grid from street lighting cables along with small generators. The generators are dependent upon a steady supply of diesel fuel or gasoline, the connections rely on periodic blackouts:

A rigger makes a new connection to a street light circuit (unknown photographer): jury-rigged connections are found in every slum around the world. Making unofficial connections is a dance with fiery death unless the power is off during a blackout. There is little information about how many are killed making unsanctioned connections to energized circuits. In most poor nations there are periodic blackouts during which time do-it-yourselfers and hired riggers climb poles and attach lines.

A rigger connects a house to live wires in the Rocinha slum in Rio. (Fred Alves, Washington Post)

Unknown photographer: the wires bring lighting, refrigerators and air conditioners: at the end of every single wire there is a television set. The desire is for all to buy and buy: the fantastic world will be the slum-dwellers’ tomorrow as long as they endure the unendurable today …

Support for the business lords’ agenda springs from the underclass’ misery and human desire for ‘improvement’. The television puts form to the multitudes’ fantasies …

Photo by Kevin Frayer (AP): a man walks past temporary high-tension power supply cables in New Delhi. It is unfair to characterize the entire country of India as a gigantic slum but the photograph is indicative. The drainage canal is both sewer and water supply for those in the surrounding neighborhood. Note the garbage dump to the left sloping into the canal. The infrastructure of India and in similarly situated parts of the world cannot support the growing human mass that depends upon it.

The lack of clean water for drinking and cleaning as well as proper waste sanitation are gigantic health problems. Large slums housing thousands often have latrines that are nothing more than open pits with boards over them. New pits are dug when the originals are filled. When the rains come the pits overflow with human waste which floods into the housing.

Slums are considered to be green due to density however the hundreds of millions who live in them are without waste-water treatment. This pollution ultimately winds up in the ocean, beaches in Rio have been closed by sewage floods from the city’s notorious favelas. Along with sewage is millions of tons of indestructible plastic waste.

The concept of slum is expandable, some forms are purposefully created and are not to be confused with anything else.

Unknown photographer: the dystopian nightmare without end, humans as lobotomized rats running in a sewer … a canal sluicing with a torrent of mechanized waste, every occupant a slave to auto manufacturers and the petroleum industry.

Jericho Turnpike in Long Island, NY (Scouting New York)

Sleepwalking Into the Future

James Howard Kunstler

Years from now, the denizens of Long Island may shake their heads in wonder and nausea as they attempt to repair the mighty mess that was made here during the 20th century. My term for this mess is the national automobile slum. I think it’s more precise than the usual generic term suburban sprawl. A slum, after all, is clearly understood to be a place that offers a very low quality of life. And the mess is everywhere. Every corner of our nation is now afflicted. The on-ramps of Hempstead aren’t any more spiritually rewarding than the ones in Beverly Hills. We’ve become a United Parking Lot of America.

We have utterly relinquished the everyday world of our nation to the automobile. I don’t think it is possible to overstate the damage that this has done to us collectively as a civilization and as individual souls. The national automobile slum is a place where the past has been obliterated and the future has been foreclosed. Since past represents our memories and the future our hope, life in a car slum is life with no memory and no hope. How many of us can gaze out over a typical highway strip like the Jericho Turnpike and imagine a hopeful future for it or for the people who will have to live with it?

Slums are variation on the theme of dehumanization. Humans are reduced to being cogs in gigantic machines or waste products. Individuals in the waste category sometimes lift themselves up by becoming drug kingpins, informal ‘mayors’, celebrities or shills for Ponzi schemes. The rest are trapped, the slums swallow them.

What is underway is the slum-ification of the entire world. The great machines cannot provide middle-class lives to all because the necessary materials are absent. If the slum-dweller cannot regularize the status of his ‘house lot’ if he cannot afford the materials to craft a permanent structure that does not leak whenever it rains, there are no others who will gain these things for him.

An abandoned, unfinished skyscraper in downtown Beijing (Glen Downs): where did all that money go? The industrial ‘solution’ is always more development but this shifts costs around, it doesn’t eliminate them. Every slum that is developed out of existence in China pops up in Africa or South America. With more humans there are more slums, eventually the new developments become slums as well.

When the fossil fuel becomes unobtainable the great auto slums of America and its wannabes will become the real things or places of ruin and abandonment.

Consider all of our precious infrastructure without the means to keep it maintained. Here are your shining cities on the hill: the slums beckon, the default future for what remains of the human race in a world that is stripped of all accessible resources.