Building the 1955 Oldsmobile and other GM car bodies at a ‘Body By Fisher’ factory in Detroit. Fisher started building horse-drawn wagons before the turn of the 19th century then turned to the horseless carriages. From 1908 though the 1920s, the company built bodies for many manufacturers including Ford Motor. Eventually Fisher became an semi-independent unit within General Motors. During the 1950s and 60s auto heyday, Fisher employed more than a 100,000 unionized workers in dozens of facilities across the country, building car bodies for GM.

This promotional film suggests the timeless quality of General Motors products even thought the products were designed to be obsolete within short periods. Americans were expected to ‘keep up with the Joneses’ and buy new cars whenever the manufacturers introduced new models, every three years. Extremely durable vehicles such as Henry Ford’s ‘Model T’ were undesirable as the makers had ever-increasing amounts of production to absorb. Makers needed their affluent customers to buy frequently, to ‘move up’ from basic models such as those made by Chevrolet to more expensive models made under the Oldsmobile, Buick and Cadillac nameplates. Older models would be traded in and resold to those who were less affluent. What made the process work was car loans, anyone could qualify as the car itself was security for the loan.

Along with the loans came insurance as a burgeoning industry. Lenders did not wish to lose the worth of their security in crashes. If a car was damaged, the insurance would pay for repairs. If the car was totaled the survivor would obtain a replacement. With insurance, car crashes were good for business.

Cars made during the immediate postwar period had infinitesimal warranties, it was ‘buyer beware’ at all times. Components failed spectacularly including transmissions, brakes and steering gear. Fisher’s highly-engineered craftsman-like bodies could not withstand corrosion. Few examples of GM’s ‘permanent quality’ from 1955 remain, most are rusted away and recycled, others were destroyed in collisions.

The emphasis on safety is ironic because American cars of this period onward were death-traps, among the most dangerous vehicles ever built.

Cars were top-heavy and bulky, overpowered with large cast-iron block engines. Pre-war models had large engines because smaller versions did not produce enough power or were noisy, vibrated excessively or were difficult to operate. Large engines were smoother and more powerful at lower RPMs. Engines improved after the war due to better material and higher craft standards, yet the large engine did not give way. Makers simply advertised their models’ increased horsepower and driving performance.

The heavy engine in the front of the car powered the rear wheels by way of the transmission and drive shaft. Consequently, cars tended to understeer. That is, the driver would turn the steering wheel to go around a curve and the car would tend to continue straight because of the arrow-head like weight in the front. The driver would compensate by turning the wheel more. At the same time, auto suspensions were primitive affairs little changed from the horse-and-wagon era. The solid rear axles were carried on leaf springs with little play, coil spring front suspensions tended to have much more travel … for a more-comfortable ride on poor quality roads. The result was a suspension that could not keep all four wheels on the road under all circumstances. The heavy vehicle weight and poor suspension had cars leaning away from turns. Body lean would unload the ‘inside’ wheels: the cheap, polyester cord bias-ply tires would lose grip. Even slow turns of 35mph under certain conditions would have the car sliding straight off the road into an obstacle or rolling over.

Brakes were also poor. The drum brakes found on most American cars faded with repeat applications. Brake linings would overheat and the hydraulic brake fluid would boil. Fittings and hoses would leak leaving drivers with nothing to stop the car but a hand brake with little more stopping power than the failed foot brakes.

If there was a wreck there was little protection for car occupants. With few exceptions, manufacturers did not offer seat belts, even as an option. The rotary door latch seen in the film was not strong enough to keep the door closed in the event of a collision. Under stress, the door would pop open, the occupants would be pitched out of the open door with the car rolling over on top of them. The steering column was a solid steel shaft that extended from the steering box forward upward and back toward the driver’s heart. In a collision the car body would detach from the frame and slide forward or the steering box would be driven backwards. The column would impale the drivers’ seat penetrating through the driver on the way. Alternatively, the heavy seat would break loose from the floor and ram the driver forward against the steering column.

One of the tasks of emergency workers was to saw through steering columns in order to remove drivers from car crashes with the columns pierced through their bodies.

The cheap door latches and lack of restraints left passengers ejected in all directions in serious crashes. The thumb-push door latch shown in the film was a killer as even modest collision force and inertia would ‘push’ the button and open the door.

Car wrecks during this period were gruesome affairs. Front seat passengers in a forward collision were simply ejected through windshields, leaving their faces, scalps, breasts, testicles and other body parts hanging from shattered glass. Paralyzing neck injuries from both front and rear collisions were common, so were multiple amputations. Quality auto bodies by Fisher would crumple in collisions trapping victims inside to bleed to death. An overturned car would have its roof collapse with the weight of the car crushing occupants inside.

Starting in the 1950s almost every US car was capable of speeds over 80 mph. Passenger restraints were limited to simple lap straps as in airplane seats: in crashes, belted occupants would be hurled forward to slam faces and heads against steel dash panels, against unpadded front seats or against control knobs that would penetrate their skulls. Door releases, window cranks and interior accessories became lacerating or impaling weapons in crashes. Gas tanks and fuel systems were unprotected and poorly mounted: collisions resulted in car fires with occupants trapped inside burning coffins. The same doors that were self-opening during modest collisions tended to become unopenable if the car was underwater or burning, particularly if the car was upside down. Injured passengers needed to maintain some presence of mind to drag themselves out of windows and away from flaming or sinking vehicles.

The fins, wheel hub spinners and chrome sheet-metal bumpers so favored by auto fashion designers became sword blades that maimed and killed all within reach. The manufacturers didn’t care, highway deaths were simply the cost of doing business.

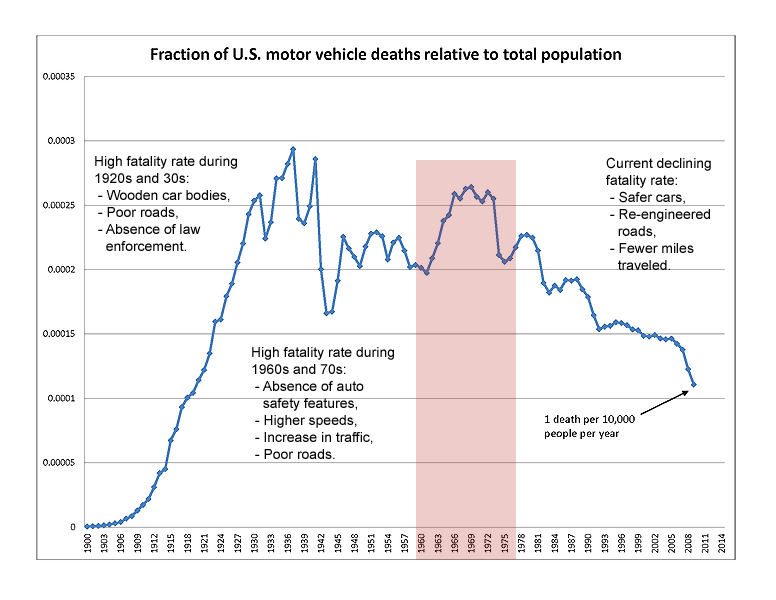

Figure 1: the US highway death rate-per-10,000, (Wikipedia, click on for big). Here we can see the twin heydays of the US auto industry: from 1908 through the 1920s and the 1950s and early 60s. The chance of death around every curve during a high-speed run down a lonely highway was — and is — part of the glamor of auto ownership. Risk, danger and fear: car death was a component of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Great Gatsby as it was to James Dean’s ‘Rebel Without a Cause’. ‘Easy Rider’ offered vacuous rage and murder on the highway as a metaphor for the meaningless Vietnam war and the consequent culture divide. Car chases and crashes became a boring/predictable element of motion pictures and television shows. Automobiles, anomie and hormones were — and still are — the ingredients of American rock-and-roll … all of these things were — and are — good for car sales.

Making and selling automobiles is a bloody business: designs in the 1920s and 30s periods were intended to ease/standardize manufacture rather than provide passenger protection. Car bodies were made with wooden components which could not withstand the forces of higher-speed impacts. At the same time, roads were poorly engineered, almost all were narrow and unmarked. Off the road was the ravine or unyielding obstacle. Cars off the road with injured occupants might not be found for days. Except in cities or developed areas there was little enforcement of traffic laws … if there were traffic laws. Most roads even city streets were unlit, some were paved with cobblestones, others with irregular concrete slabs. The first high-speed, limited access road in the US did not appear until 1940, in Pennsylvania.

The public furor over seat belts during the 1960s was remarkable. Manufacturers resisted belts because of the implication that both cars and drivers were unsafe. Belts also cost money which the cheap manufacturers were loathe to spend. Throughout the fifties and early sixties, drivers wanting belts had to order them from aftermarket manufacturers and have them installed privately. Eventually seat belts were offered as options on luxury models.

During the 1960s, manufacturers started putting largest V-8 engines from luxury sedans and station wagons into smaller commuter-cars. The higher power combined with lower vehicle weigh increased potential vehicle speed. Buyers looking for the larger engines could also buy four-speed manual transmissions, stiffer front suspensions and wider ‘performance’ tires. The US ‘muscle cars’ were still primitive compared to European performance sedans, they were nevertheless able to kill thousands of American teenagers ‘looking for a thrill’ on public highways.

The US industry was complacent. A feature of US automobiles was poor fuel economy. Starting in the 1920s most American vehicles would travel about 15 miles or less on a gallon of gasoline. Following the gas shortages of the 1970s, the public demanded more economical vehicles which Detroit found itself unable to produce.

The casual disregard for human life on the highways continued until the mid-1960s when German and Japanese imports started appearing in US markets with safer, more economical designs. Ralph Nader published his ‘Unsafe at Any Speed’, which lambasted the industry … General Motors in particular. Foreign manufacturers offered standard models with seat belts and collapsible steering columns, strong unit-bodies that protected the passengers, disc brakes, four-wheel independent suspension, radial tires, smaller engines and better attention to vehicle assembly. Insurance companies and legislatures began mandating these and other common sense safety features in all cars.

Cars gained redundant brake systems so the failure of one hydraulic circuit would not leave the car without brakes. Fuel systems were isolated from crash areas. Manufacturers designed and installed energy-absorbing crumple zones, air bags, lap-and-shoulder belts for all passengers as standard equipment, padded dashboards, stronger door latches, recessed dash controls and better steering. Starting in 1973, cars in California were required to have pollution controls to recycle unburned fuel back into the fuel system … this led to computerized engine controls and catalytic converters. Detroit management knew of these ‘innovations’ and had in fact invented some of them, manufacturers knew how to build safer, economical cars immediately after the war, they simply refused to do so, focusing instead on restyling conventional models and advertising.

During the 1970s, highways were re-engineered, surfaces were widened with pull-off areas and force-dissipating Armco- and Jersey barriers installed along right-of-ways to keep careening vehicles on the highway. Bridge abutments, culverts, poles and sign-posts were removed to the side away from the travel lanes, exit- and turn areas were made more gradual. Stop signs, lighting, ‘traffic calming’ devices were installed including medians, curbs, speed bumps and rumble-strips were installed to deter traffic and annoy drivers into slowing down. Law enforcement campaigns against impaired drivers has also made the roads safer. Enter the speed camera.

Since the 1950s use of cars has mushroomed. Benefits gained by safer designs were overcome by the massive increase in car numbers, the wear on infrastructure, the numbers of older, mechanically defective vehicles, the increase in elderly, impaired or unschooled drivers along with the disparity in vehicle sizes. Small economy sedans and motorcycles share crowded roads with heavy transport trucks and bloated ‘light vehicles’ such as SUVs.

Grant Wood, “Death on the Ridge Road”.

Auto manufacture has spread around the world and Detroit has been passed by. A deadly industry currently faces its own demise. The auto industry life-cycle in can be seen in Detroit for those with the wit to look: birth, an adolescent ‘heyday’ of public enthusiasm and industrial expansion, a long maturity leading to senescence and final ruin. With the unraveling of the auto industry comes the unraveling of everything that is dependent upon it. Just as Detroit has fallen, so too will fall Japan and Germany, Korea and the other auto-manufacturing centers. They must fall because fuel is too valuable to waste in non-productive gadgets and because the debt needed to build and buy the gadgets has become too costly.

In an industry’s infancy, debt is taken on to buy the tools of production and for customers to pay for the industry’s products. With the passage of time, the debt an industry takes on buys increased competition. Debt also flows to the owners away from tools. At the end, debt taken on by the industry services the debts taken on previously, nothing remains for any other purpose. The auto industry helped win the Second World War by making a vast inventory of war goods with public financing. After the war, the US government assisted the reconstruction of overseas’ competitors who devastated the industries in Detroit, then the city itself.

The Fisher factory today is a shell used by the City of Detroit to store impounded automobiles. In place of the thousands of workers who labored in Fisher Body’s plants, there are now computers to design and build the tooling, robots to assemble the parts into finished cars. One of the intended products of industry was plentiful jobs: industrialization is a complete failure with regard to jobs.

In 2009, both General Motors and Chrysler faced liquidation but were bailed out instead. Ford Motor avoided the others’ fate by borrowing from the Treasury and the Federal Reserve discount window. Auto industry overproduces because too much credit has been directed toward it. Cars in their making and operation are extraordinarily costly, in particular the petroleum needed to run the cars and all that has to do with them. Although pollution costs have not been accounted for, they do exist and they are significant. As it was with safety belts, the industry steadfastly ignores these costs as if ignorance can make them disappear.

Cars have killed 3 million Americans in the past 100 years, more than all American wars put together. According to the World Health Organization, cars have killed 1.2 millions persons world-wide per year since 2007. Each death is someone who will never buy another car. Car making is a bloody business, but one that has wormed its way into public affection. The car business’ time is passing, in the end the heyday of the car will be no different from the heyday of the clipper ship. The cost of doing business is the demise of the car business itself.