ZeroHedge published the following article a couple of days ago but it escaped notice until Mish pointed it out:

On The Verge Of A Historic Inversion In Shadow Banking

Submitted by Tyler Durden

While everyone’s attention was focused on details surrounding the household sector in the recently released Q1 Flow of Funds report (ours included), something much more important happened in the US economy from a flow perspective, something which, in fact, has not happened since December of 1995, when liabilities in the deposit-free US Shadow Banking system for the first time ever became larger than liabilities held by traditional financial institutions, or those whose funding comes primarily from deposits. As a reminder, Zero Hedge has been covering the topic of Shadow Banking for over two years, as it is our contention that this massive, and virtually undiscussed component of the US real economy (that which is never covered by hobby economists’ three letter economic theories used to validate socialism, or even any version of (neo-)Keynesianism as shadow banking in its proper, virulent form did not exist until the late 1990s and yet is the same size as total US GDP!), is, on the margin, the most important one: in fact one that defines, or at least should, monetary policy more than most imagine, and also explains why despite trillions in new money having been created out of thin air, the flow through into the general economy has been negligible.

The big idea here is that central banks are accommodating, that there will be a flood of new currency spewing forth that results in hyper-inflation. ZeroHedge and ‘Tyler Durden’ have been beating the ‘money printing by the Fed’ drum for too long. Comes now Tyler who decides they don’t really print money after all.

The source of this revelation is a report from the New York Fed: ‘Shadow Banking’ by Zoltan Pozsar, Tobias Adrian, Adam Ashcraft and Hayley Boesky. Says the New York Fed:

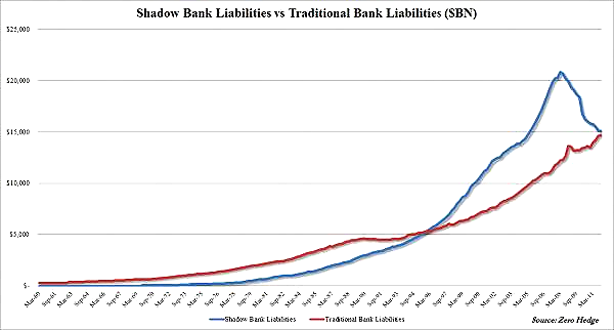

As illustrated in Figure 1, the gross measure of shadow bank liabilities grew to a size of nearly $22 trillion in June 2007. We also plot total traditional banking liabilities in comparison, which were around $14 trillion in 2007.The size of the shadow banking system has contracted substantially since the peak in 2007. In comparison, total liabilities of the banking sector have continued to grow throughout the crisis. The governmental liquidity facilities and guarantee schemes introduced since the summer of 2007 helped ease the $5 trillion contraction in the size of the shadow banking system, thereby protecting the broader economy from the dangers of a collapse in the supply of credit as the financial crisis unfolded. While these programs were only temporary in nature, given the still significant size of the shadow banking system and its inherent fragility due to exposure to runs by wholesale funding providers, one open question is the extent to which some shadow banking activities should have more permanent access to official backstops, and increased oversight, on a

more permanent basis.

Ya gotta love the Fed: if a finance institution is worthlessly decrepit, it needs more tender lovin’ from the central bank, ‘permanent access to official backstops’.

The Fedsters also use the word ‘permanent’ twice in the same sentence, a cringe-inducing writer’s faux pas!

Meanwhile, the word from the Undertow repeated ad-nauseum in various articles has private sector balance sheet contracting as central bank balances expand for zero net gain. Central banks do not create new money, in fact cannot. They recycle old loans. They rather want people to believe … that they will create new money, by doing so they create ‘expectations’ for it. Somehow this theater is to ‘fix’ the world’s unraveling: to substitute for the needed 20 million or so barrels of additional cheap crude oil per day.

Here is more from ZeroHedge:

… US Shadow Banking liabilities – a combination of Money Market funds, GSE and Agency paper, Asset-Backed paper, Funding Corporations, Open market paper and of course, Repos – hit a gargantuan $21 trillion in March 2008. They have tumbled ever since, printing at just under $15 trillion at the end of March 2012, the lowest number since March 2005 when shadow banking liabilities were soaring. This is an epic $6 trillion in flow being taken out of credit-money circulation, with a $143 billion drop in Q1 alone! (blue line on the chart below).

Figure 1: Chart by ZeroHedge (click on for big), comparison of banking vs. shadow banking liabilities with banking including depository institutions.

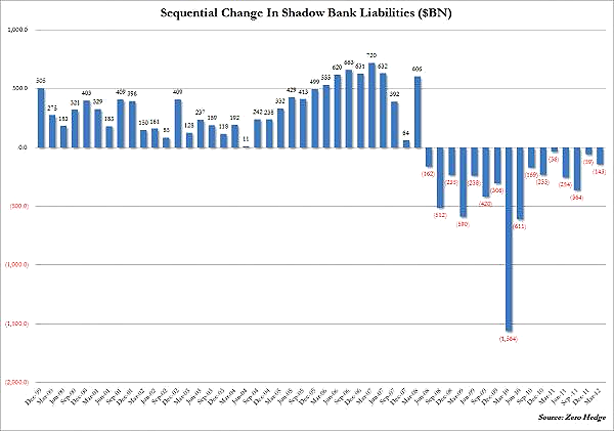

In fact over the past 16 quarters there has not been a single increase in the total notional contained within shadow liabilities.The chart below shows perfectly just where the credit bubble popped: a bubble which has affected shadow banking far more than normal credit transformational conduits.

Figure 2: Finance liabilities ex- depository institutions. Here is where the finance system balance sheets contract. Sez Zero:

It is precisely this ongoing contraction that the Fed does all it can, via traditional financial means, to plug as continued declines in Shadow Banking notionals lead to precisely where we are now – a sideways “Austrian” market, in which no new credit-money money comes in or leaves.

What the hell is an Austrian market?

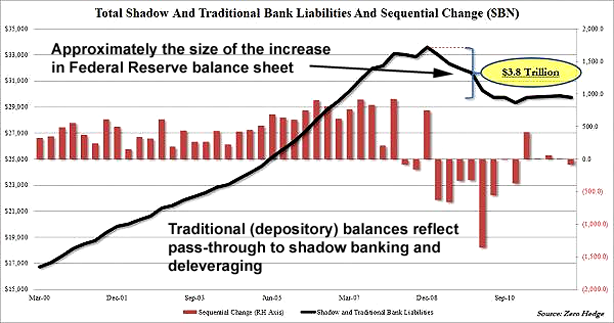

In fact, as the (first) chart shows, while the collapse in shadow banking has been somewhat offset by increasing liabilities at traditional banks solely courtesy of the Fed, the reality is that for two years in a row, consolidated US financial liabilities amount to just shy of $30 trillion and have barely budged. As long as this number is not increasing (or decreasing) substantially, the US stock market has virtually no chance of moving higher (or lower) materially.What is worse is that even when accounting for offsetting traditional bank liabilities, on a consolidated basis, the US total financial sector is still an epic $3.8 trillion below its all time highs, just above $33 trillion. Unless and until this $3.8 trillion hole is plugged, one thing is certain: risk is not going anywhere (also notable is that consolidated liabilities in Q1 declined by $86.2 billion at a time when the Fed was engaged in Twist but that is for Ben Bernanke to worry about, not us).

Figure 3: The Fed bailed out the non-banking sector using the banks as conduits. More Zero:

So what is this “historic inversion” referenced in the title?As some may have noticed looking at Figure 1, as shadow banking continues to collapse, it has to be offset by increasing conventional bank liabilities: for the most part real cash (technically electronic) deposits. And as of March 31, the spread between Shadow Banking and traditional financial liabilities has collapsed to just $206 billion, after hitting a record $8.7 trillion in March 2008. It is also important because the last time shadow banking as notional overtook the conventional banking system was back in December of 1995. Next time we update this chart, the blue line will be below the red one for the first time in 17 years.

As far as the Undertow is concerned, this is a big deal. It’s not simply a prediction that has turned out to be true but a fundamental point of analysis … regarding the finance system itself. Without so many words, Tyler Durden has just come out and said the Fed does not print money.

This runs counter to the long-running inflationary theater that has been used to justify contractionary policies at the national level, as well as inflation-beating investment strategies for individuals. Only trouble is that these justifications aren’t relevant: the central bank balance sheet expands as the private sector balances contract. Here’s Mish, who provided the heads-up:

Zero Hedge Provides Empirical Proof of Deflation (However, He Does Not Even Realize It)

Zero Hedge, citing a Federal Reserve Bank of New York report on Shadow Banking, makes (without even realizing it) a sure-fire case for deflation.

I encourage you to visit the link shown above, but also take a look at On The Verge Of A Historic Inversion In Shadow Banking by Zero Hedge.

[…]

Deflation It Is!

Mish notes the same ‘Austrian’ market:

There is nothing “sideways” about it. The charts clearly show credit money is indeed leaving (contracting) to the tune of a whopping $6 trillion since March 2008.Interestingly, Zero Hedge did not mention “deflation” once in his post.

Yet, those charts, without a doubt, depict deflation if one accurately describes inflation and deflation as measures of credit, not prices.

Based on real-world experience of what is most important, here is my definition: Inflation is a net increase of money supply and credit with credit marked to market.

Deflation is the opposite, a net decrease of money supply and credit with credit marked to market.

If one woodenly sticks to the view that inflation and deflation are about prices (while ignoring a devastating collapse in housing), then yes, the US is still in a period of inflation.

Likewise, if one foolishly sticks to measures of money supply like M1, M2, or TMS (true money supply) by Michael Pollaro, then the US is also in a period of inflation.

Real World Viewpoint

Neither money supply nor the CPI can adequately explain interest rates, housing prices, lack of jobs, and numerous other real-world phenomena.

In the real-world, in a credit-based economy, it is credit that matters.

Sorry Mish, in the real world, in an automobile-based economy, it is crude oil that matters.

The above charts show the real story. That story explains 10-year treasury yields at 1.61% and 2-year yields at .29% even though the CPI is 1.7% year-over-year.Those charts also show why hyperinflationists are in an alternate universe and why proponents of “huge inflation but not hyperinflation” are on Mars.

Not only does money supply or the rest inadequately explain modernity’s woes, neither does balance sheet deflation. The problem is the so-called ‘productive’ economy, which has never paid for itself. Mish writes his articles then jumps in his car that must be paid for to the tune of five- or eight- or ten thousand dollars per year by doing something other than driving. There must be borrowing by either Mish or his customers: multiplied by the hundreds of millions of Mishes in the greater world motoring aimlessly in circles. More borrowing still … is required for roads, bridges, streetlights, parking lots, tract houses, military machines, wars, insurance, finance, concrete towers and those who fill them: everything in sight on borrowed ‘money’ … decade after decade.

Here, then is the reason for the “interest rates, housing prices, lack of jobs, and numerous other real-world phenomena.” Our physical economy is unproductive and utterly dependent upon the productivity of debt. When debt fails for any reason to be fruitful — too much taken on to retire and service old debts — the entire economy unravels, as it is doing right now.

‘Money printing’ is inaccurate and false: central banks cannot create new money, they are balance sheet constrained. They cannot lend without collateral. They cannot lend above the ‘face price’ of the collateral, which is almost always another loan. What central banks do is shuffle the custody of loans between agents, moving up or down the yield curve in the process. The central bank can offer credit as long as there is ‘good’ collateral offered by the private sector lenders. Without the good collateral — exhausted resources are not useful — the banks cannot lend.

If they choose to do so they become no different from the insolvent firms they seek to rescue. Firms get into trouble making unsecured loans using leverage, nothing can be gained by the central bank making the exact same loans.

Meanwhile, another hallowed Bretton-Woods era institution the Bank for International Settlements has offered its latest annual report. Here is Izabella Kaminska (Financial Times):

Central bank existential crisis confirmed

The BIS Annual report released this Sunday is jam-packed with data, charts, observations and analysis. Joseph has already stuck up some of the most compelling…

But one of the other key points to emerge is in its chapter on the “limits of monetary policy”. There is, it appears, a marked admission that central banks may be losing control.

We don’t mean that in the old cynical sense we’ve heard before — that because central banks are zero-bound they are running out of tools — we mean it existentially.

What’s more, the theme is growing in official circles.

Pimco’s Mohammed El-Erian was the most recent high profile name to throw light on the issue. Commenting on the Fed’s latest decision to extend Operation Twist last week, El-Erian explicitly stated that lacking fiscal support, solitary Fed activism would only alter the functioning of markets, contaminate price discovery and distort capital allocation.

Already, the viability of several segments – from money markets to insurance and from pension provision to suppliers of daily market liquidity, all of whom provide financial services to companies and individuals – has been undermined. The Fed has also conditioned many market participants to believe in a policy put for both equities and bonds. And other government agencies are relieved to have the policy spotlight remain away from their damaging inactivity.

The Fed feels compelled to act in some way (i.e. extending Operation Twist) rather than doing nothing because it knows political brinkmanship binds the hands of the Treasury and its ability to apply the correct course of action. That course of action is very aruably extending the debt ceiling, the only possible move which may be able to overcome the issues faced by the Fed today. Bernanke has hinted as much already.

In that context markets should really be calling for Treasury action, not Fed action.

Defective monetary policy or fiscal policy, what’s the difference? Here’s the take from the BIS itself:

IV. The limits of monetary policy

In the major advanced economies, policy rates remain very low and central bank balance sheets continue to expand in the wake of new rounds of balance sheet policy measures. These extraordinarily accommodative monetary conditions are being transmitted to emerging market economies in the form of undesirable exchange rate and capital flow volatility. As a consequence, the stance of monetary policy is accommodative globally.

Central banks’ decisive actions to contain the crisis have played a crucial role in preventing a financial meltdown and in supporting faltering economies. But there are limits to what monetary policy can do. It can provide liquidity, but it cannot solve underlying solvency problems. Failing to appreciate the limits of monetary policy can lead to central banks being overburdened, with potentially serious adverse consequences. Prolonged and aggressive monetary accommodation has side effects that may delay the return to a self-sustaining recovery and may create risks for financial and price stability globally. The growing gap between what central banks are expected to deliver and what they can actually deliver could in the longer term undermine their credibility and operational autonomy.

The central banks money-shuffling hasn’t accomplished very much, after repeat sessions there are obvious diminished returns. An outcome of easing policies is dollar- and yen carry trades, good only for putting unemployed currency traders back to work.

First, prolonged unusually accommodative monetary conditions mask underlying balance sheet problems and reduce incentives to address them head-on. Necessary fiscal consolidation and structural reform to restore fiscal sustainability could be delayed. Indeed, as discussed in more detail in Chapter V, more determined action by sovereigns is needed to restore their risk-free status, which is essential for both macroeconomic and financial stability in the longer term.

The only policy guaranteed to restore fiscal sustainability is stringent energy and resource conservation which is currently avoided at all costs. The inevitable outcome of all the strategies is event-driven conservation.

Similarly, large-scale asset purchases and unconditional liquidity support together with very low interest rates can undermine the perceived need to deal with banks’ impaired assets. Banks are indeed still struggling with the legacy of the global financial crisis and often depend heavily on central bank funding. And low interest rates reduce the opportunity cost of carrying non- performing loans and may lead banks to overestimate repayment capacity. All this could perpetuate weak balance sheets and lead to a mis-allocation of credit. Evidence that deleveraging by US households came through a reduction in new loans rather than writedowns of unsustainable debt points to the relevance of such mechanisms at the current juncture.

Without new loans the loan businesses fail, the central banks have become the last line of defense. When these fail-become irrelevant there is nothing more for the establishment to offer.

Second, monetary easing may over time undermine banks’ profitability. The level of short-term interest rates and the slope of the yield curve are both positively associated with banks’ net interest income as a result of their positive effects on deposit margins and on the returns from maturity transformation, respectively. True, there is evidence from a sample of internationally active banks that, in the period 2008–10, monetary easing boosted banks’ profitability, supporting the rebuilding of capital bases. The negative effects associated with the reduction in the short-term policy rate were more than offset by the steepening in the slope of the yield curve. However, an environment of protracted low interest rates characterized by both low short-term interest rates and flattened yield curves would ultimately lead to an erosion of banks’ interest income. Signs of this happening are already present, as the more recent flattening of the yield curve in the United States and United Kingdom has gone hand in hand with a drop in banks’ net interest margin.

Paul Krugman has made the same argument.

Low returns on fixed income assets also create difficulties for life insurance companies and pension funds. Serious negative profit margin problems associated with the low interest rate environment contributed to a number of life insurance company failures in Japan in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Today, insurance companies and pension funds have partly insulated themselves from these effects, either by hedging interest rate risk, or by moving towards unit-linked insurance products or defined contribution schemes. These measures, however, eventually shift risks onto households and other financial institutions.

Sooner or later, every form of asset is thrown into the furnace. This is because all of them are claims made against future productivity which itself is nothing but a fairy tale.

Third, low short- and long-term interest rates may create risks of renewed excessive risk-taking. Countering widespread risk aversion was one important motivation for the exceptional monetary accommodation provided by central banks in response to the global financial crisis. However, low interest rates can over time foster the build-up of financial vulnerabilities by triggering a search for yield in unwelcome segments. There is ample empirical evidence that this channel played an important role in the run-up to the financial crisis. Recent large trading losses by some financial institutions may indicate pockets of excessive risk-taking and require scrutiny.

The BIS does not recognize criminal activities that take place under its nose.

Fourth, aggressive and protracted monetary accommodation may distort financial markets. Low interest rates and central bank balance sheet policy measures have changed the dynamics of overnight money markets, which may complicate the exit from monetary accommodation.

The report goes on to describe carry trades and capital flooding in and out of countries. Meanwhile, the credit demands grow, driven by exponentially compounding debt-service costs. There is nothing the central banks can do to address this ballooning problem. They cannot ‘kill’ credit nor can the create new money. When the central bank retires a loan it is because another loan in a greater amount is made elsewhere. They fill holes by digging new ones. Meanwhile, the central banks would ordinarily influence interest rates but millions of motorists buying gasoline every day determine the worth of money.

The central banks cannot fix anything, only fake it. Bank depositors take notice reducing confidence in the banking system. There are too many expectations loaded onto the central banks, which have become the last line of defense for a derelict system. When the banks’ theater stops working there is nothing else for the banks — or the establishment — to do.

The BIS suggests a trans-national ‘unitary’ central bank, a ‘Super-Fed’. Best for it arrive with a couple of trillion barrels of crude oil.

All roads lead back to resource depletion and unsecured credit, the epitaph of modernity.

R.I.P.