The greatest part of Venice, Italy found itself underwater a few days ago:

‘The reaction is to cry’: In flooded Venice, visitors take selfies as residents reel

Washington Post

The tourists stayed when flooding arrived this week. But Venetians say the toll of repeated inundation has led to a sense that life in one of the world’s most improbable and spellbinding cities is becoming unviable.

It isn’t just one or two coastal cities threatened by rising ocean waters, it is all of them: Shanghai, Tokyo, Saigon, Dhaka, Jakarta, Miami, New York City, London, Mumbai. Even cities that are currently well protected with flood defenses such as Amsterdam, Rotterdam and New Orleans are at risk; also inland cities such as Cairo and Washington, DC. As ‘Time Machine Earth’ retreats into the Pliocene, 2+ million years ago, polar and glacial ice is melting and sea levels are steadily increasing. Much of this rise is literally baked into a ‘cake’ as latest increases in carbon gases haven’t registered their effects, yet.

Areas don’t have to be permanently inundated to be rendered uninhabitable. Repeat cycles of extreme rainfall, flash floods or tidal surges cause damage to buildings, bridges, roads, subways, and underground utilities that become too costly to repair or mitigate. The post-tropical storm Sandy flooding did billions of dollars worth of damage to New York City subways. Repeated floods of similar magnitude would financially cripple the marginally solvent transit system and render it unusable. Without its subway, New York City would no longer function as a commercial city; perhaps only as a tourist attraction like Venice is today. The foregoing presumes all else in New York remains the same, which would not be the case after repeat floods.

In the Pliocene, temperatures were 2°- 3°C higher than recent pre-industrial period; both polar ice caps largely melted away. Sea levels were 80+ meters higher than they are now. In real estate terms, 80 meters means Wall Street towers would be inundated to the 20th floor. Venice would be 79 meters underwater. Much of Netherlands, Denmark, Bangladesh and almost all of the world’s coastal cities would be gone, so would south Florida. The Gulf of Mexico would extend up the Mississippi valley to Memphis.

This week, in an event known as an “acqua alta,” a tide of more the six feet surged in from the Adriatic Sea and quickly covered 85 percent of the city. The flooding was the most severe in 50 years. But similar if less drastic flooding is becoming common. Some experts warn that Venice could be underwater within a century.

“One of the things I’m looking at, you know, is people are tired… You’re starting to see that in people’s conversations and faces that they’re weary and tired” from repeated bouts of coastal flooding. Unable to elevate their historic structures, have resorted to trying out their own flood protection barriers.

Houston, one of the world’s great ‘energy cities’:

A Rice University study published earlier this month found that nearly 20 percent of flood victims surveyed in the wake of Hurricane Harvey reported post-flood PTSD, depression and anxiety. And more than 70 percent said the prospect of future flood events was a source of worry.Harvey was the third “500-year” rain event to hit Southeast Texas in three years. This week, Tropical Storm Imelda also earned that distinction, as some areas received more than 40 inches of rain, paralyzing the area as highways morphed into parking lots and first responders performed more than 2,000 rescues Thursday alone. And many residents are now asking themselves: Is Houston worth it?

Imagine how Houston residents will feel after their city is under fifty meters of water or even ten. Also imagine where these folks will go after their Great Flood. Outside of communist China, there are exactly zero vacant cities waiting on higher ground for new occupants. The locals there will certainly have plenty of their own problems and won’t be too keen on welcoming tens of millions of climate refugees, just like most folks aren’t pleased with the current relative trickle.

Problems scale geometrically against the level of rising water. Our habit of taking each economic problem in isolation from the rest suggests flood problems are episodic and localized. As long as a particular flooding event is brief, it can be made note of, then the notes filed away. Business returns to normal after debris is swept up and the water is gone. The floods in Venice are a local condition resulting from the location of the city at the north end of the Adriatic Sea. Sirocco winds and storms from north Africa along with high seasonal tides push seawater hundreds of miles up the relatively narrow channel between the Italian shoreline and the Balkan coast. The surge of water northward has nowhere to go except into the streets and plazas (and buildings) of Venice. This combination of wind and tide is intermittent, so is flooding from storms. When the wind stops and the tide changes the water flows away. Puddles are mopped up and the storekeepers ready themselves for the horde of cruise ship passengers looking for souvenirs. The same tides and weather don’t flood Naples or Barcelona. Damage from tropical cyclones is limited to areas within the storms’ paths. A typhoon in Manila has no immediate effect in Buenos Aires. Rainfall from a slow-moving weather system may flood an area one year then not again for decades. Due to intermittency, flood events are unpleasant but manageable.

Water levels that rise generally due to melting polar ice render all coasts equally vulnerable. When world sea levels are a half meter higher, Venice, Italy will flood almost continuously … so will Venice, California. There will be damage everywhere: Shanghai, Tokyo, Saigon, Dhaka, Jakarta, Miami, New York City … Manila and Buenos Aires. Flooding in these places will be unmanageable. The choice will have to be made to abandon some- or all of these places at enormous cost or try to defend against the water at expense that may prove insufficient … also at enormous cost.

Effective mitigation efforts would also have to scale geometrically. When there are only a few places with seawater flooding problems, dikes, locks, tidal gates and dams prevent flooding as they do in Amsterdam and New Orleans. Protecting all the coastal areas at risk including cities, port facilities, nuclear power stations, desalinization plants, refineries, military bases, farmlsnd and other infrastructure would be an immense task, likely beyond current industrial capacity. Ironically, this effort would be necessary to provide the protections that are right now available for free. There are also no guarantees any affordable mitigation would be sufficient longer term. Dike systems that protect against three meters of water fail at four meters. At 60 meters, efforts toward any mitigation at all would be a laughable gesture; a waste of time and resources.

Migration costs scale geometrically. The thousands of families who moved from New Orleans to Atlanta after Hurricane Katrina represented a modest increase in housing demand in Atlanta. Newcomers doubled up with friends and family or they took short-term lodging in motels and in vacant apartments. New Orleans was not permanently submerged or destroyed. After the storm waters were pumped out, the government provided inexpensive ‘FEMA’ trailers as temporary housing for those looking to return. These trailers were cramped and uncomfortable, some gassed inmates with formaldehyde, but residents could return to the city and remain until their houses were rebuilt. In Atlanta, the local market for housing was able to absorb the permanent newcomers. Meanwhile, the federal government and insurance companies provided funds to repair wind and water damage as well as improve flood defenses.

Millions of families migrating from the coasts would be a second great flood. Multitudes — billions — would be on the move around the world. As human population has expanded it has become urbanized, most of the largest urban centers are at sea level. Because there isn’t enough replacement housing, people looking to escape the water would take shelter where they could, filling sprawling camps or shanty towns. Around the world, a billion humans live in slums right now. This is without any floods; with them, the slum population will increase significantly, perhaps more than double.

This is more than a matter of simple replacement. The flood disruptions would be enduring; unlike New Orleans after Katrina, there would be little chance of return in any meaningful sense. Good housing, land- and tax value, adequate employment, vital services and commerce would be ‘swapped’ for ad-hoc settlements with few services or possibilities for earning a living. Trade- and social networks of trust that formed around specific places over periods of years would be disrupted as these places are abandoned. It is hard to see how would this be good for any sort of business, even those which have so far profited from the misery of others.

The microeconomic measurements of opportunity cost and depreciation of capital stock are difficult to make because disruptions tend to compound unpredictably with scale. Theories of replacement- or pent up demand break down when cities and countries are ruined and citizens are destitute. Venice is old, certainly depreciated, but what is it actually worth? It is certainly more than the income the city generates from tourism. What would it take in dollars and cents to recover tourist income after it is lost to the flood, or would such a thing be possible? Industrial economies at this moment are unable to gain positive returns. We borrow dollars to return pennies of GDP. We find it difficult to repair and replace infrastructure that is inadequate or has simply worn out. How we might build replacements on the needed scale with persistent flooding and disasters underway is hard to imagine.

Providing food, water and sanitation for the multitudes would be a related, almost biblical crisis. Disruptions would include clogged ports, transport breakdowns and malfunctioning markets. These would be amplified by climate-related problems ‘down on the farm’: loss of topsoil fertility, water shortages, desertification and diminished crop yields caused by rising temperatures and changes in prevailing weather patterns. Ironically, with the floods, there would be diminished ability to access drinking water along with food. With the world economy unable meet current obligations, it is hard to see how these compounding needs will be met.

It won’t matter if the migrants came at once or over a period of years or even decades: the destruction of assets and the process of relocation are not productive. There is no return to persons losing their homes and businesses. Once-costly housing at the point of abandonment is worth very little or nothing, so is once-valuable land that is underwater. Retreating families would generally lack the means to obtain permanent housing pretty much anywhere. At the same time those with better fortunes would cause a steady increase in demand on higher ground, making shelter even less affordable for the rest. Confronted with the scale of the problems and their permanence, government- and private administrators would act as they do now: stand off to the side and wring their hands! Meanwhile, the same institutions would be seen as the agents of failure and ruin; they would become irrelevant or overthrown with this chaotic process feeding back unpredictably into the crisis.

It is unlikely the US would provide funds after New Orleans floods repeatedly, certainly not after the city’s flood defenses are overcome. As with New York’s subway system, repeat fixes to New Orleans and its levees would ultimately cost more than the rest of our seemingly ‘rich’ country can afford. The US can create money or borrow infinite amounts but the country cannot create or borrow work which requires energy and materials; these are physical things that cannot be cajoled into service by public relations departments or deployed by fraud. The same resources that have been relentlessly exploited for the past 150 years would be called upon for further service. There is increasing doubt as to whether resources will be available, or what a pauperized — and flood-damaged — country can muster. Would the country have any money or would the money have worth? Would there would be enough funds in circulation to gain energy or work or would citizens, faced with the prospect of more destruction, abandon ‘money’ altogether?

All of this leaves out other climate- related disruptions: wars, expanded range of diseases and other pests, fires and debilitating heat. All of these carry their own costs that compound flooding disruptions in unpredictable ways.

Following along this line of reasoning: the ‘first mover advantage’ lies with those who can understand what is taking place under their noses. When does this occur? Simply posing the question risks precipitating its own, unbearable answer. Inhabitants of threatened cities would want to be second movers if they can’t be first. As with finance crises, once losses are recognized there is a stampede of ‘investors’ rushing to exit their positions all at once. The same thing will happen as flood losses are recognized. It’s reasonable that individuals paying attention in Miami and Savannah and other low-lying areas have already cashed out and decamped to more secure ground. After this cadre there is some undetermined mover as the ‘marginal agent’ who triggers the rout. What comes after? Nobody wants to find out.

Poor Venice. The creative labor of generations over a period of 1,500 years = “Meh, it’s just old junk.”

Unknown photographer; Dresden after Allied bombing raids of February 13 -15, 1945

Venice is a form of human and civilizational capital accumulated slowly over the course of centuries. As capital, Venice has value, the latter being a characteristic of non-renewable natural resources such as gold or petroleum. Even as gold can be salvaged after a disaster, there is no possible ‘replacement Venice’, nor can it be renewed. Just as there are no adequate replacements for the cities destroyed by aerial bombing during World War Two, there can only be new, uglier buildings in the old places or — in the case of Venice — a farcical copy in some out of the way place in China or Las Vegas.

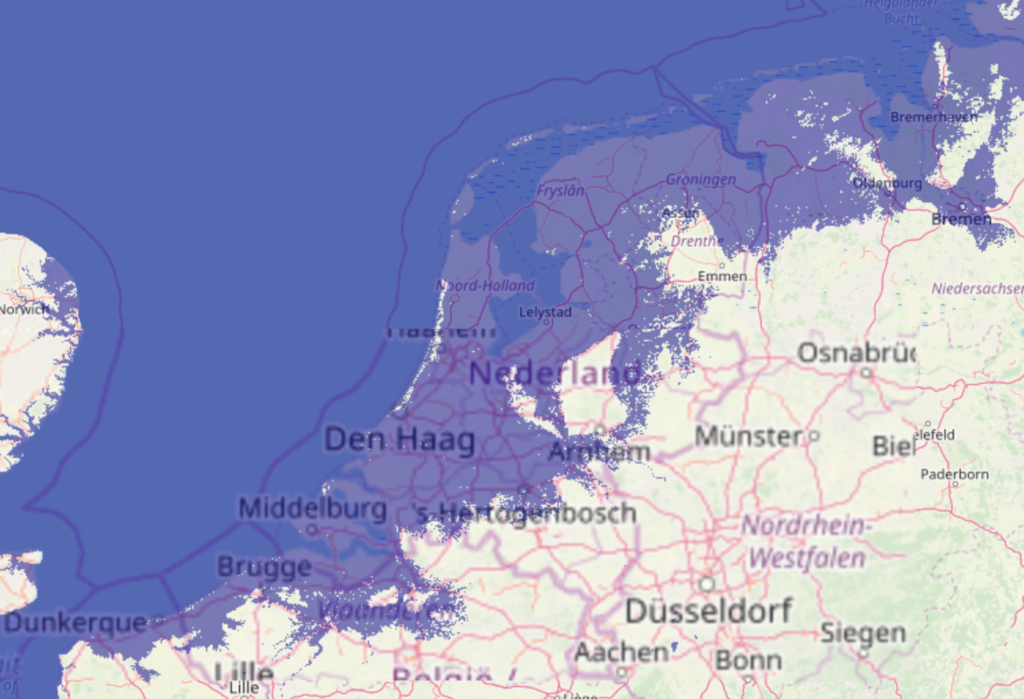

Is Amsterdam worth it? Netherlands under 9 meters of water, Floodmap

It’s impossible to say how long the process of capital annihilation will take for Venice to become a soggy ruin. It could happen a few years from now should one of the great polar ice sheets break up. Already, the warmer ocean has undermined the seaward layers of ice in Antarctica and Greenland that have so far held land bound glaciers in place.

West Antarctica is considered the most vulnerable of Earth’s three major ice sheets. It rests in a deep, broad bowl that dips thousands of feet below sea level – exposing it to warm ocean currents. It would raise sea level by 11 feet if it collapsed.

Industrial humans don’t bother with consequences while they play with fire, just like they never bothered in the past. Costs have so far resided comfortably in the future as ‘someone else’s problem’. All of a sudden the future is at our doorsteps and costs are outrunning our ability to meet them. Those who were supposed to be the bag holders for today’s follies turn out to be us and our children.

“In this war of every man againstevery man[nature] nothing can be unjust. The notions of right and wrong, justice and injustice have no place there. Where there is no common power, there is no law; and where there is no law, there is no injustice. In war the two chief virtues are force and fraud. Justice and injustice are not among the faculties of the body or of the mind. If they were, they could be in a man who was alone in the world, as his senses and passions can. They are qualities that relate to men in society, not in solitude. A further fact about the state of war of every man againstevery man[nature]: in it there is no such thing as ownership, no legal control, no distinction between mine and thine. Rather, anything that a man can get is his for as long as he can keep it.”

— Thomas Hobbes ‘Leviathan’

Values: we used to have them, but they were slaughtered on Flanders Fields along with ten million children. We used to have prices but bailing out billionaires turns out to have rendered the numbers nonsensical. What do we have now? Cheap illusions and too much water.