The Christmas present nobody wants sits under the tree: a worldwide finance crisis along with an establishment that appears to be coming apart at the seams.

The status quo is unraveling from all sides, at the top especially, where managers cannot conceal their panic:

When the captain of the ship starts taking the covers off the lifeboats there is a problem. https://t.co/mhASE3sPE1

— steve from virginia (@econundertow) December 24, 2018

Oops!

“Every banker knows that if he must prove he is worthy of credit, however good might be his arguments, in fact his credit is gone.”

— Walter Bagehot

The government marshals its forces of borrowing in order to prop up the lenders as per usual. Yet, the lenders have been propped up for years. The bosses demand lower lending rates even as these same rates are at- or below historical lows. What more can be done and to what end? The rates and props deployed during and after prior crises have contributed to the immediate peril as well as everything that has led up to it. There is no cure to be had in additional doses of the same poison that currently looks to kill us.

By questioning whether lenders are worthy of credit the Secretary sinks his own battleship: “Every banker knows …” well, perhaps not. He inadvertently reveals truths: that lenders are vital but are also vulnerable. Vital in that our economy does not pay its own way, it cannot. The industrial economy is reductive rather than productive: its primary ‘good’ is entropy. Business relies on the continuing increase of bank money to draw future resource capital toward the present. Without the lenders and the credit they provide the modern, industrial economy stalls then comes undone. If our economy could meet its own expenses out of cash flow it would do so. What the Secretary admits without doing so directly is our economy cannot afford itself.

That we cannot afford our economy is its immediate vulnerability. Asymmetries within the lending regime such as maturity mismatches make it fragile. The regime depends on a marginal agent or class of agents that sets conditions for all the others. Keynes notwithstanding, a certain level of borrowing restraint, something short of universal borrowing has little affect on the system as a whole. But, some percentage of economic agents must borrow with a fraction of that borrowing deployed to service and retire existing debts. Small leaks- or water over the top of a dike will not damage it but one small leak too many will wash the dike away. In the same way, a small percentage of non-performing loans or defaults is tolerable to the system, a portion of lender reserves and equity is set aside to resolve these as they appear. Then, there is one default too many for whatever reason … this is disaster! The ‘capital’ structure of the lender is upset; this calls into scrutiny the capitalization of all other lenders that are similarly situated. Uncertainty is rapid and corrosive, given time it widens into a self-amplifying spiral of insolvency. This is what occurred in 1929 and 2008 and what looks to be underway right this minute.

Compounding the problem, the marginal borrower is impossible to identify or for immediate institutional convenience is disregarded. The tiny leak with the potential to destroy the dike can be one of any (very large) number. Globalization has rendered the marginal agent opaque; official denial and central bank happy talk permits known problems to fester. The marginal borrower can be an individual or a firm, or a class like Chinese peer-to-peer lenders, Italian footwear manufacturers or Spanish residential real estate speculators and the banks that supply these with funds. Eventually, all of them together become marginal. Structured finance operates outside the reach of policy makers at the same time are tightly bound to all the others by way of swaps, corresponding- and exchange lenders, counterparty agreements, derivatives-based hedges and money markets. Like a flood, marginality propagates outward, with the ‘new’ marginal borrowers becoming major banks, dark money pools, bond- and derivatives market makers, national governments and foreign exchange. In any event, agents cannot be compelled to borrow and in a crisis refuse to do so. Insolvent, zombie-like walking dead firms which continue to borrow/lend in the aggregate are lethal to the regime: they can only offer the (fraudulent) appearance of a cure while delaying the inevitable reckoning. Accounts cannot be overdrawn indefinitely, it is impossible to borrow out of debt. “If something cannot go on forever, it will stop,” says economist Herbert Stein. No amount of marginal borrowers can rescue a system that is foundationally bankrupt.

… this is after hundreds of trillion$ have been borrowed around the world already. The simple fact of the trillions suggests the managers are inept and perhaps insane. Our debts have grown beyond human scale, even the billionaires all together cannot hope to retire them, in fact their borrowings have contributed significantly to the total. Along with their managers, these stupendous debts fade to irrelevance in the practical sense; they can never be repaid. They are empty claims against resources that have long since been converted into useless waste. Machines that are dependent upon credit for their very existence cannot repay, certainly not labor which is feeble; which is otherwise depreciated, subordinated and oversupplied.

This is all part of the current crisis, it may indeed be its entirety. Whether the markets are repricing (in)competence, (in)solvency, systemic bankruptcy or perhaps all of the above; it is too soon to tell.

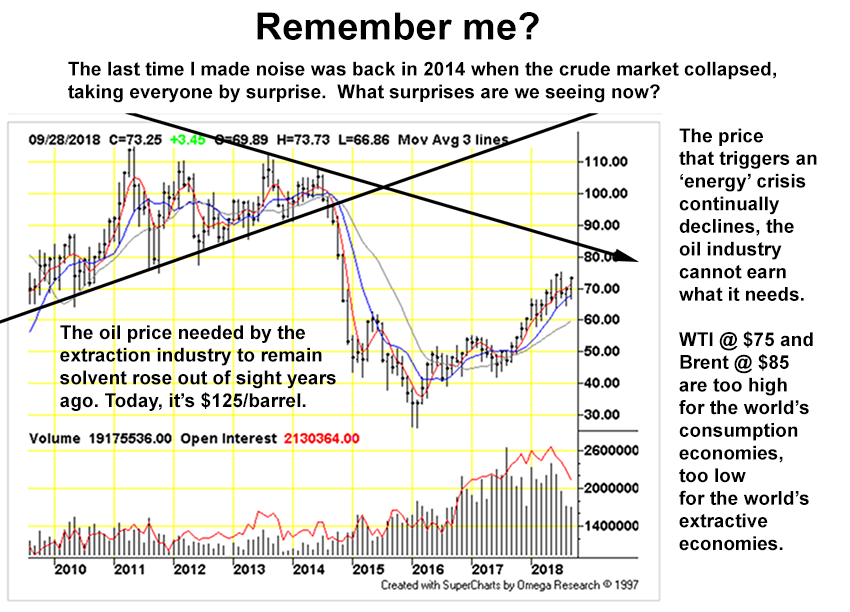

Figure 1: What is our over-extracted world worth? The underlying problem is resource stripping and its consequences. If that is being priced in right now we are in big trouble. Chart by TFC Charts (click on for big). The current crisis could not be predicted as was the oil price plunge in 2014, but it was inevitable nevertheless. Our economy requires cheap oil to run but the cheaper oil is exhausted, what remains is unaffordable. Low cost credit has offered the (fraudulent) appearance of a cure … but it has only delayed the inevitable reckoning.

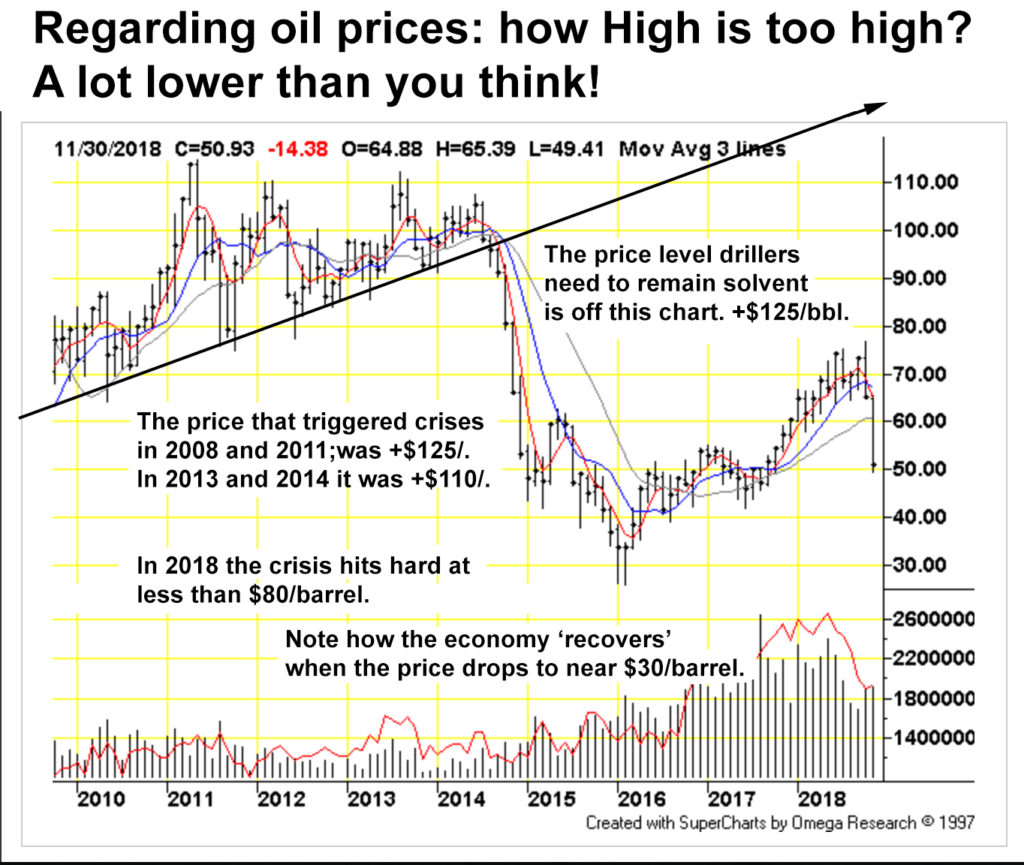

A few years ago, the oil price that triggered crises was over $100 per barrel. We have been creeping toward a crisis for the past several months at $80 per barrel. Time and waste leave us less wealthy than we pretend to be …

Figure 2: Compare the likely crisis price suggested a few months ago. We clearly cannot afford $75 oil, higher prices are out of reach. At the same time, the drillers cannot stay in business selling their product below cost. What is common = access to credit which turns out to be the means by which resources are allocated. The customers are broke.