An argument can be made that under our present circumstances analysis of the declining economic order is not particularly relevant: it is best to look forward rather than pick over the past, to let the current regime fall apart and build something new and better on the ruins. While there is something to be said for that approach, we need to understand where we are … and to do so not just to ‘know the enemy’ or grab him by the belt. We are likely to see a post-industrial economy reassembled out of existing components; evolution as much as revolution. How things actually function is important to know, the challenge is to parse analysis from advertizing. Within economics, the truth is liberating to the extent that speaking it will likely get you fired.

Economic processes are fairly straightforward to understand piecemeal but can be much harder when taken together. Much of this is by design, some is happenstance. We are conditioned to think in terms of linear narratives with beginnings, middles and ends. We have been well-trained by television; we like simple, we like dramatic, we like violent, we like ‘happily-ever-after’.

The past 400 years offers proofs that there are no happy endings to industrialization, only varying degrees of ruin. Modernity hollows itself out, the ‘advance of progress’ within nations is like the rot of a body afflicted with gangrene. The flow of funds within economies is similar to the flow of hydraulic fluid in an automatic transmission; there are main-streams, feedback loops and pressure differentials, all offering different outcomes depending on which gear you select and what pedal you push. After some time, the transmission stops working and so does the car … nobody can figure out why.

Individual economic processes can be linear but each is a sub-component of others; narratives multiply, segue into others or intertwine to form multi-layered complex webs which are closely-coupled and brittle. Analysts specialize: they tend to focus on individual processes so as to keep their narratives intact while serving the needs of their sponsors. Life within voluntary constraints is pleasant for the economist who excludes all the bits of unhappy reality outside his specific area of expertise. Hence, the heavy emphasis on conventional econometrics, neoclassical- and DSGE analysis from the establishment: these disciplines self-edit by design.

They also self-edit for a purpose: our present regime is a debtonomy. Lenders conjure endogenous money or debt as the means to private riches for themselves and their clients; tycoons borrow immense sums for their own gain leaving others to meet the costs. This process makes up the entirety of our economic system. Debtonomics follows Fisher 1933, also Minsky 1980 and Keen 2014.

Debtonomics: an indictment as much as a description:

— All economic activity is subject to the First Law, where the costs of managing any surplus increase along with it until at some point the costs exceed what the surplus is worth. Due to the conservation of energy- and matter; there can be no possible work- or goods output greater than the sum of inputs. Debt, false accounting and the use of fossil fuels have allowed us to pretend while shifting costs to others.

— On a cash-flow basis our consumption economy is continually ‘underwater’, the gap between capital cost and system return is financed with debt. When input prices are low, the amount to be financed is affordable. Scarcity reprices resource capital, at some point both capital and necessary credit become too costly. These costs cannot be shifted, the outcome is ‘demand destruction’, currently underway around the world.

— Industrial firms are loss-making enterprises, incapable of organic returns. That the industrial economy cannot afford itself is self-evident: if the enterprise was productive it would retire its own debts. A firm can be a government entity or a business; the larger the size of the firms the greater is aggregated costs and the more it or its customers need to borrow — first law.

— Borrowing represents artificial returns; firms borrow against their own accounts, against the accounts of their customers, against the state or against foreign exchange. Firms’ success has little to do with products but rather their ability to wheedle loans.

— Besides borrowing, an ‘outside’ activity of firms is converting capital — non-renewable natural resources — into waste. The shiny and glamorous wasting process is collateral for loans; the more effectively firms waste or enable it by others, the more efficiently the firm is able to borrow. Another activity is mispricing resource capital; by manipulation in markets and by purposefully refusing to identify capital as such.

— Because waste does not offer a return, the foundation of modern economic development is provision of loans. The industrial country requires its own currency; a national treasury with the ability to offer collateral; strong, well- managed and properly funded banks at all levels; an independent lender of last resort and a system of jurisprudence: the rule of law, private property, enforceable contracts and regulatory constraints on practices. Any two countries possessed of the same material advantages … of natural resources, manpower, education, transportation access, and liberal governments; where one possesses the instruments of credit and the other does not … the first country will industrialize while the second will depend upon the credit of the first and become its subject. Absence of organic credit provision is why nations are unsuccessful at modern development.

Provision of loans is why bankers are ascendant, why they hold the world hostage, why they are free from any accountability for their own crimes and excesses: banks create money by lending it into existence. If there are no banks, there are no loans, if there are no loans there is no money and no industrialization.

Firms borrow from their own bankers or from credit markets, or by issuing shares so that others borrow for the firm’s benefit. Firms borrow against the accounts of their customers whenever these (customers) take on loans to purchase the firms’ goods. As a consequence, business ‘profits’ and any retained earnings are simply the continued ability of firms’ customers to continue borrowing over time.

Firms borrow against the accounts of the state because states generally have greater borrowing capacity than firms and at lower cost. Firms position themselves to gain access to the stream of funds from the state. Access takes the form of direct (contract) payments, subsidies and tax advantages. Holding currency is a form of borrowing against the account of the state: in a debtonomy all cash currency is the unpaid debt of others. Firms borrow against foreign exchange when imported currency becomes collateral for loans in the native currency.

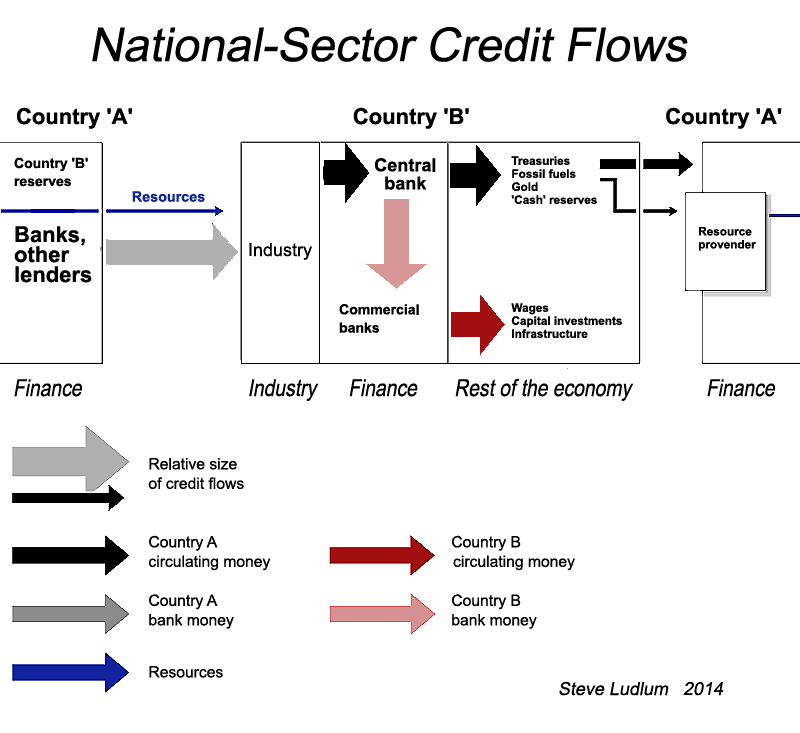

Visualizing flows of funds.

Currency flow diagram of a fictional economy showing how borrowing from foreign exchange works. Funds originate at the left @ ‘Country A’ and flow to the right, by way of ‘Country B’ and back to the beginning where the cycle is (hopefully) repeated. Keep in mind, flows are not static like a graphic. Future graphs of this particular model would show the same components and flows having more-or-less identical relationships, perhaps at a different overall scale.

Figure 1: The arrows on the chart represent flows and are roughly to scale. Credit originates as bank money in country ‘A’ and is sent to country ‘B’ in exchange for goods’ exports or as foreign direct investment (FDI). These funds are aggregated at country ‘B’ central bank where they are used as collateral for loans in local currency. By this simple means the exporter doubles his purchasing power: he holds both the imported currency as well as the newly created currency which is distributed into the economy. This multiplication of purchasing power is why countries are eager to export as well as borrow overseas currencies.

Some of the country ‘A’ currency becomes foreign exchange reserves, some is swapped for gold or other resource capital while the rest is recycled back to country ‘A’ where it becomes ‘vendor financing’ for subsequent rounds of export purchases and FDI. Here, ‘currency’ means the forms of a country’s money and credit in aggregate.

| FUNDING | The flow of foreign exchange (black arrows) |

| REFUNDING | Flow from the central bank to the commercial banks |

| DISTRIBUTION | The flow from the banks into the economy |

When a country creates local currency against overseas collateral the nominal rate of exchange is arbitrary. One unit of currency ‘A’ might be worth one unit of currency ‘B’ or five and a half units or a thousand … or vice-versa. It is purchasing power that is multiplied; that of the one currency being equivalent to that of the other at all times regardless of exchange rate. Purchasing power relationship is inelastic and tightly coupled by way of arbitrage; the simultaneous purchase or sale of common goods with both currencies, such as a third-party currency or petroleum. For this reason, both the black and red arrows in country ‘B’s economy are the same size, they represent purchasing power.

It is in the interests of the trading- and investing partners to maintain exchange rate stability over time, so that nominal and real purchasing power are aligned. Countries and central banks attempt to do so by way of currency pegs, interventions or by adjusting interest rates. Purchasing power borrowed against foreign exchange is always constrained by collateral, it cannot be ‘adjusted’ by cheating because any imbalance between funds and purchasing power is exploited by arbitrageurs.

Conventional analysis sees the world as a dependency of the US Federal Reserve money printing. ‘Hot money’ dollars are hustled overseas by way of carry trades, with speculators looking to exploit interest- and exchange rate differentials for short-term gains. Funds flow toward developing countries when rates favor the trades, they recoil when rates turn against speculators. Inbound flows push asset prices higher, when flows reverse assets are dumped and prices decline, including currency. To support currency prices central banks adjust short term policy rates by taking deposits, hoping to lure the speculators back.

This analysis is overly simplistic and incomplete. The Federal Reserve cannot create new money, it is collateral constrained. Its foreign exchange interventions are zero-sum affairs. Countries gain dollars by exporting petroleum or manufactured goods, borrowing against their American customers as well as by way of FDI, these flows are relatively inelastic and unaffected by borrowing costs. The scale of borrowing against foreign exchange is immense; amounting to trillions of US dollars in China alone; Forex borrowing represents the largest component of lending support for developing countries as these generally do not have organic alternatives. The uncertain potential rise of a few basis points will not affect the demand for dollar loans from overseas’ borrowers. Their choice is to borrow regardless of interest cost or miss the latest chance to develop.

Whereas lenders’ long-term returns from interest payments can be substantial, short-term returns are relatively modest. The greater gain from lending is the requirement on the part of the borrower to repay with money that is more costly to him than the loan is to the lender. Bank money costs the lender almost nothing to create as it requires only keyboard entries. The borrower must repay with circulating money; he cannot create repayment on his keyboard but must beg, steal or more likely borrow repayment- or have it borrowed by others in his name (bailout). Whereas interest cost tends to be a small fixed percentage of the principal payable over time, the expense of circulating money is determined by its availability in the marketplace, by supply and demand. When circulating money is scarce the real worth of repayment can be much greater than the nominal balance due, yet this is invariably when the demand to repay is fiercest, as during a margin call. If the loan is secured and the borrower cannot repay, he must surrender collateral along with other rights. These are always worth more than a keyboard entry.

In this sense, lending malpractice is outright theft rather than usury; with the banks offering loans that cost them nothing as the means to gain high-cost money as well as the real goods and labor that are pledged as collateral. There is also risk: when there is no collateral to seize in the place of circulating money, both borrower and lender are ruined.

When bank money changes hands it becomes circulating money. By acceptance, the recipient banks validate the ledger entries as ‘money’ as well as their worth. At the same time, the borrowers accepts their obligation to retire the loans on the lender’s terms with interest.

Inflation and deflation implications

Conventionally, inflation and deflation represent the inverse relationship between funds and purchasing power. Inflation is increase in unsecured loans, the increase of funds in circulation over time without a corresponding increase in purchasing power. This is also ‘economic growth’. Deflation is the decrease of funds relative to purchasing power. Periods of deflation follows episodes of inflation over long cycles; funds balloon and unit-purchasing power declines followed by reversion to mean.

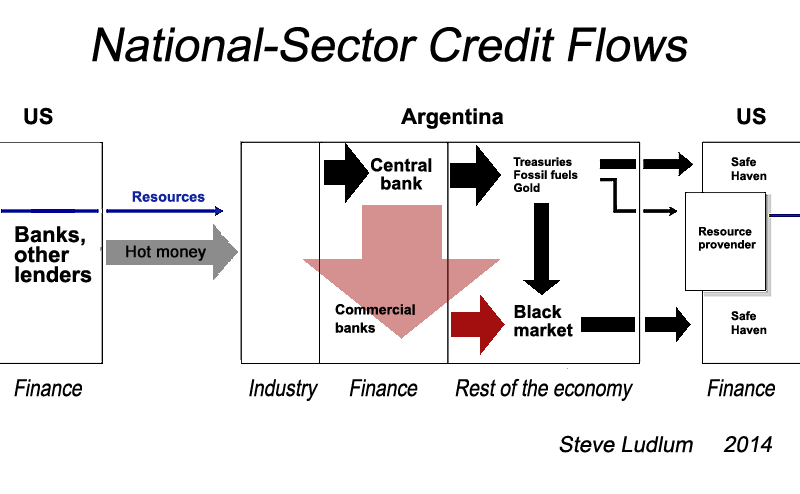

Model of Argentina national credit flows:

Figure 2: This could be the chart for Brazil, South Africa, Venezuela, Ukraine, Turkey along with dozens of other developing countries. Argentina’s problem sticks out like a big, pink thumb: unsecured loans by the central bank. This is seen as the increased flow within the refunding channel, costs (losses) are directed to the commercial banks which attempt to distribute them into the economy. The resulting imbalance between funds (pesos) and purchasing power (dollars) is exploited by arbitrageurs (anyone with access to pesos) … instead of being absorbed by the economy, losses are forced back onto the commercial banks which become progressively weaker until they fail. Meanwhile, the same economy is emptied out of purchasing power as the ‘loss-pushing’ process is self-amplifying.

Argentina is poster child for long-running policy errors: the greatest being repeated efforts to industrialize which invariably end in disaster, the other being the central bank making unsecured loans. As it does so it becomes insolvent which in turn triggers bank runs.

Any two countries possessed of the same material advantages … where one possesses the instruments of credit and the other does not … the first country will industrialize while the second will depend upon the credit of the first and become its subject. Absence of organic credit provision is why nations are unsuccessful at modern development.

So it is with Argentina: without organic credit the country is dependent upon overseas loans. Hyperinflation is persistent across South America because private banks are historically weak and unable to pass costs onto others. The banks cannot provide the credit needed to meet politicians’ delusion of grandeur, partly because credit by itself is unable to provide anything real. To gain credit, countries import dollars and other foreign currencies while central banks are called upon by leadership interests to supplement the commercial banks’ unsecured lending with their own. The outcome is vanishing lenders of last resort, systemic insolvency and runs. Repeated cycles of (hyper)inflation, bank runs and crises pulverize the banks … which are able to recover somewhat with more outside loans … only to collapse when the crisis re-emerges a few years later. Latin American countries cannot free themselves from dead-money debts or develop as they wish.

Whether countries such as Argentina are suited to American-style industrial development is never examined nor are alternative approaches given consideration, only the same cycle of borrowing and failure repeated over and over.

Banks are weak because managers are cronies of government elites, other interests are ignored, or worse. Bankers simply steal depositor funds and leave the country. Unsurprisingly, citizens don’t trust the banks, they do as much of their business as possible with cash and hold savings in the form of real estate or other hard goods that cannot be easily stolen or replicated into worthlessness. Like most countries with inflation problems, Argentina has been in a frenzy to develop, to ‘get rich quick’, to become industrialized.

Argentine lenders have one foot out of the country, together they represent the transmission channel for foreign currency loans. The returns on these loans are appealing to yield-starved overseas investors while spreads are positive for lenders. The pressure to lend in dollars and other foreign currencies is unrelenting. The outcome has been foreign currency flows into Argentina followed by droughts as locals, outside speculators and the lenders themselves remove the funds out of harm’s way as fast as they can.

… the requirement on the part of the borrower to repay with money that is more costly to him than the loan is to the lender.

When dollars become scarce, Argentines cannot refinance maturing loans. Firms and citizens compete with each other to gain dollars, the contest crowds out commerce and becomes the country’s entire economy … which becomes the big reason why Argentina’s central bank makes unsecured loans.

Hyperinflation is complex and there are many historical episodes with multiple causes. The hyperinflation known as the Price Revolution occurred in Europe during the 16th century due to the flow of gold and silver into Spain after its conquest of the New World; also population increase, the decline of goods output due to wars, the introduction of new banking instruments as well as currency debasements. Hyperinflation in the US during the Revolution was amplified by British counterfeiting. Hyperinflation in Wiemar Republic was accompanied by similar outbreaks in Hungary, Poland and France. A common characteristic of all hyperinflation episodes is countries desperate to develop at any price along with weak- or non-existent private sector banks unable to distribute central bank costs onto others.

Hyperinflation = central bank losses (costs) forced onto commercial banking sector. The central bank attempts to expand purchasing power by adding to the refunding channel flow. Commercial banks attempt to distribute their losses into the economy which they cannot do because increases in the amounts being distributed have the same purchasing power as original foreign exchange funds.

Because the purchasing power of a currency is equal to that of the collateral, commercial banks borrowing from the central bank are continually underwater; a peso returned by a bank to its depositor is always worth more than the replacement they borrow from the central bank. The banks demand more pesos from the central bank to ‘make up the losses with volume’. Meanwhile, the unsecured peso refunding from the central bank is the incentive for depositors to remove funds as quickly as possible and change them for dollars. Both depositors and outside speculators become bankers in miniature, using increasing amounts of pesos to bid for diminishing amounts of ever- more costly dollars in the black markets which are then spirited out of the country. If the central bank attempts to defend a particular exchange rate the dollar arbitrage process accelerates until the country is emptied of dollars. Once the establishment abandons the official rate, depositors use pesos to strip the country of goods, leaving the currency with zero collateral and worthless as a result.

Non-bank businesses refuse to accept pesos — as every increment of time represents a loss of peso purchasing power, every good is worth more than money. Listening to pleas from the banking sector, the central bank believes the economy is running out of funds — when it is really running out of purchasing power.

Deflationary bubble

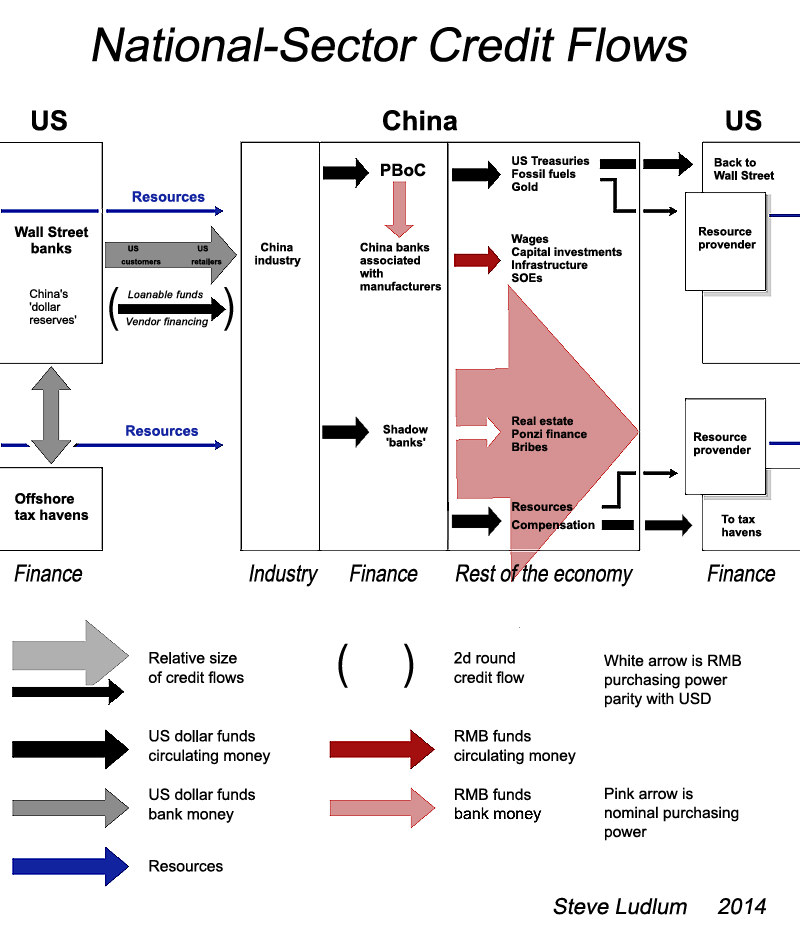

Figure 3: China’s loans-against-forex model is like Argentina’s and the rest because China is dependent upon dollar- and other hard currency flows as collateral for domestic loans. This contradicts conventional analysis which has China as a US creditor. China cannot create dollars or dollar credit; China ‘lends’ energy (coal) and human labor to the US in the form of manufactured goods, which cost the country very little to produce. Repayment is in the form of dollar loans which cost Wall Street almost nothing to produce.

China’s energy flows are not on this model, China’s real energy costs and externalities are not on any of China’s models.

Any two countries possessed of the same material advantages … where one possesses the instruments of credit and the other does not …

Who says the Chinese cannot innovate? The Chinese have created two parallel dollar economies within one country. Dollars flow by way of US customers and retailers to Chinese manufacturers. Some are forwarded to the Peoples Bank of China at the official exchange rate where purchasing power is replicated in the form of secured RMB loans into the Chinese economy. The balance are diverted by manufacturers into the loan shark economy where they become quasi-collateral for as many RMB loans as the market will bear. This lending is universally unsecured: when there is no collateral to seize in the place of circulating money, both borrower and lender are ruined.

In China there is no refunding channel between the central bank and shadow finance. The shadow banks are very strong and have distributed their losses into the economy for a long time, these losses have simply not been recognized. Deflation occurs when these losses are finally measured, when inflated Chinese assets are marked to market.

Dollar funds to the PBoC become foreign currency reserves, some of these are swapped for gold or other resource capital while the rest are recycled back to the US where they become vendor financing for subsequent rounds of export purchases and FDI as indicated by parenthesis. Foreign exchange dollars flowing to shadow banking are simply stolen by Chinese elites, shipped out of the country to offshore tax havens by Chinese elites.

There is something in this for everyone: elites claim with straight faces that shadow banking provides loans that the above-ground lenders are unwilling to offer. Within the official sector the relationship between purchasing power and exchange rate is stable; the Chinese establishment pegs the RMB to the dollar. There is organic credit provision; the central bank is careful not make unsecured loans. The official exchange rate allows Chinese officials to insist to the West that their currency is appreciating … for public-relations purposes. The unofficial rate is a de-facto RMB depreciation which continues China’s export advantage for manufacturers and provides funds for more over-development which in turn becomes part of the Chinese ‘growth narrative’ … all of which is used to wheedle more dollar loans.

Analysts suggest that Chinese forex reserves can be deployed to bailout shadow lenders however there is no refunding channel between the PBoC and shadow banks. Because shadow banking costs have already been distributed into the Chinese economy, all that remains is for losses to be recognized, the only other alternative is kick the can down the road and pray. The central bank cannot ‘bail out’ the shadow banks as they are simply shells erected to enable the theft of forex reserves. Any redeployed reserves would be stolen as well. This would starve manufacturers of customers who would lack vendor credit with which to purchase Chinese goods. Because shadow banks are strong, any unsecured central bank lending would be distributed into the Chinese economy as more unrecognized losses. Attempting to bail out shadow banks would precipitate the deflation crisis the Chinese establishment is desperate to avoid: flight of dollar collateral => decline in RMB purchasing power => recognition of losses => bank insolvency and runs out of banks.

Credit cannot expand forever; the ‘Minsky Moment’ occurs when the cost of servicing (unsecured) debt plus the cost of running the actual economy exceeds the cash flow that can be generated by more borrowing.

Observations and remedies.

All claims and money-funds are promises to deliver some good or work in the future. During credit expansions, all promises are held in the same high regard. As results fail to measure up, some promises are held more highly than others. At the end of the cycle the promises are recognized for what they really are; lies.

— Governments are not a hyperinflationary factor where they do not directly issue currency other than to make demands of the central bank and ignore law-breaking.

— Velocity of money or rate of transactions re-using the same funds is not a hyperinflationary factor.

— Hyperinflation is a form of currency arbitrage.

— A remedy to corral inflation is to reduce system leverage by adopting a loanable funds model.

— Increase recognition of the real gains from lending. Allow debt repayment in kind: settlement of ledger ‘bank money’ loans with ledger repayments.

— Countries need to reduce borrowing from overseas lenders and dependency upon them at the same time. A way must be found to penalize overseas lenders short of (inevitable) economic collapse.

— Make use of local- regional currencies as sub-components of national currencies: increase the numbers of ‘central banks’. Increasing the diversity of participants interrupts the feedback loop necessary for inflation- or hyperinflation to take hold. Users are able to switch from an issuer’s inflated notes to alternates. Currency stability within the US during the 19th century is attributed to the gold standard but is more likely the result of free-banking and divers local currencies and issuers, along with the limited convertibility to gold. Currency worth was measured by exchange with ordinary goods and differences ironed out by discounting and arbitrage.

— Introduce peer-to-peer systems that allow users to be their own banks for the purpose of transactions.

— Adopt a scientific unit measurement for money following Le Système International d’Unités, or ‘SI’. Just as there are universally recognized kilograms, moles and amperes, there would be a standard for money that directly relates to the other standards. Prior to the use of abstract reserve funds, foreign exchange ‘money’ was metal — gold or silver — measured by weight rather than worth, and thus universal in all countries.

— Underway is a deflationary finance crisis as losses within major economies emerge, both collateral worth and loans against it are marked down to zero, banks- and credit-dependent industries fail. There is no cure for deflation just as there are no remedies for dying — only palliatives. A strategy is to voluntarily recognize losses before they emerge on their own and assign them to the malefactors who are responsible for them, Doing so will set examples and prevent future cost shifting.

— The larger remedy is to recognize the failure of industrialization and move on to some other fashion trend. Argentina’s repeated attempts to modernize have left the country with dead-money dollar debts it cannot hope to retire; it is bankrupt, it will default. It should start over with a new plan that does not include consumer products, factories or ‘progress’. China strips the world of resources endangering the life-support for all of life … so some tycoons can accumulate stolen symbols. This is insanity.

— Even after a great collapse, the world will still spin.

| The gain from lending | Borrower must repay with money that is more costly to him than the loan is to the lender. |

| Funding | The flow of foreign exchange |

| Refunding | Flow from the central bank to the commercial banks |

| Distribution | The flow from the banks into the economy |

| Ordinary inflation | Expansion of unsecured credit, bubbles, also ‘economic growth’ |

| Hyperinflation | Central bank costs/losses forced onto commercial banking sector |

| Deflation | Recognition of commercial bank losses already distributed into the economy |

| Strong banks (First Law) | Banks able to distribute their losses into the economy |

| Weak Banks | Banks unable to manage or distribute losses |