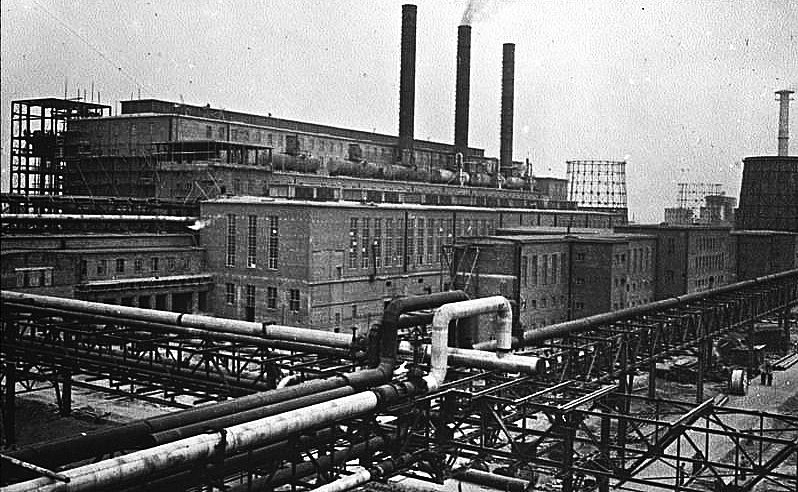

Unknown photographer (Bundesarchiv): The central powerhouse of the IG Auschwitz ‘Buna’ chemical complex at Monowice, Poland, in 1944. This giant factory was built by the chemical firm IG Farben to produce synthetic rubber, motor fuels, styrene and other compounds for the Third Reich, using raw materials mined nearby. The plant was a monument to brutality, built largely by tens of thousands of Jews and other slaves press-ganged across Europe by the German SS and ‘rented’ to Farben. Unlike much of wartime German manufacturing, toiling under the lash of Allied bombing; set up in flimsy sheds, in caves or even out in the open, the Buna facility was built of permanent materials to the highest standard. The intention was to produce wartime supplies for the German military during the years of conquest, then commercial plastics after the war was won. It was also meant to put the German stamp on defeated Poland, a permanent landmark for a thousand-year empire.

Farben was a cartel created in 1925 by combining the firms BASF, Hoechst, Cassella and Chemische Fabrik Kalle, Bayer, Chemische Fabrik vorm. Weiler Ter Meer, Chemische Fabrik Griesheim-Elektron and Agfa. These firms were founded beginning in the mid- 19th century, to synthesize dyes and related compounds from coal tar, a toxic material left over from the manufacture of illuminating gas. By the time the combine was formalized, interests had expanded to fuel, fertilizer and pesticides, cosmetics, non-ferrous metals, explosives, pharmaceuticals, reagents; also construction, mining and materials. The leading firm within the Farben combine was BASF, which had become dominant by way of the high pressure hydrogenation processes it developed beginning in 1912.

During that year Fritz Haber and assistant Robert Le Rossignol learned how to produce ammonia by combining atmospheric nitrogen with hydrogen from methane in a pressure vessel at high temperature in the presence of a catalyst. Engineer Carl Bosch at BASF expanded the process to the industrial scale. Arguably one of humanity’s significant inventions, synthesized ammonia represented a superabundance of fertilizer, allowing crop yields to increase geometrically without the need to increase the area of land under cultivation. The Haber process was soon combined with the Ostwald Process to synthesize nitric acid which together produces ammonium nitrate; this allowed for nearly unlimited supply of explosives and propellants. The timely adoption of nitrate synthesis at the industrial scale right before the beginning of World War One allowed Germany to wage war against its neighbors even as supplies of natural nitrates were cut off by British naval blockade.

In 1913, Friedrich Bergius patented a process for converting lignite coal to liquid fuel by hydrogenation under high pressure and temperature in the presence of a catalyst. Theodor Goldschmidt, a businessman and chemist with family background in the dye business built a facility utilizing the Bergius process to produce liquid hydrocarbons which became operational after the war. Ultimately, Bergius’ patent was sold to BASF where Carl Bosch perfected- then expanded the process. Starting in 1934, Farben (as Brabag) constructed a dozen coal-to-liquids plants capable of producing at full capacity as much to four million tons of synthetic gasoline and other fuels per year. In 1925, Franz Fischer and Hans Tropsch developed a complimentary coal-to-liquids process that likewise involved passing feedstocks through a catalyst at high pressure and temperatures. The output of the two processes together was sufficient to meet the entire military requirement for gasoline with synthetic fuel until allied bombing destroyed most of the plants and fuel transport.

In 1929 Walter Bach (for Farben) developed a process to produce synthetic styrene-butadiene rubber (SBR) trade named as Buna-S. There were other formulations for synthetic rubber and to some degree Farben had a hand in all of them. including types developed in the US and the USSR by Sergey Lebedev; these were all places lacking a native source of natural rubber. Farben built several facilities to manufacture Buna in Germany and occupied lands including the plant at Monowice. Together these factories were able to meed the German military demand for rubber until they were, like the fuel plants, destroyed or rendered useless by Allied bombers.

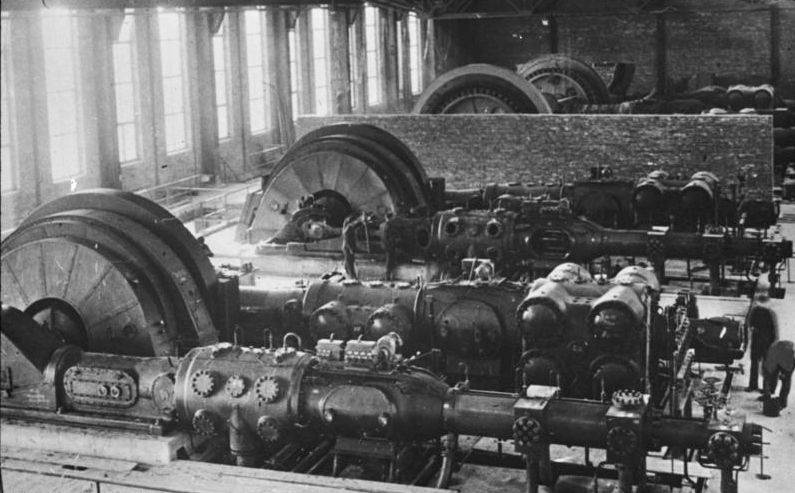

Unknown photographer (Bundesarchiv), Compressor station in IG Auschwitz Buna hydrogenation facility in Monowice. The scale of these compressors can be seen by noting the figures on the far right and in the center.

In 1937, Otto Bayer (Farben) developed the chemistry to produce urethanes which today are ubiquitous in adhesives, coatings, paint, insulation and packaging. Farben chemists also developed polystyrene and epoxies, organophosphate pesticides; also photographic film, X-ray plates and developing chemicals; also pharmaceuticals including phenobarbitol and the first antibiotics; also solvents, synthetic fibers and dyes; reagents and chemicals for refining, also catalysts, lubricants and special materials for high temperature applications. One of the production centers within the sprawling Buna factory was intended to synthesize glycol compounds used for explosives, also chemical warfare agents including precursors for the nerve gas Tabun. Glycol is a component of anti-freeze.

The 1925 consolidation created Farben as Europe’s largest company; it was also the world’s largest chemical company; a top-four largest industrial firm after General Motors, US Steel and John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil of New Jersey. Operating through hundreds of subsidiaries and merger agreements, the greatest proportion of the firm’s business was outside of Germany. Until the war, Farben was the source of the bulk of pre-WWII Germany’s foreign exchange.

Farben was extraordinarily inventive. A reason was the company did not skimp on critical investments: from The Official 1945 Report of U.S. Congress on IG Farben;

Vast sums were devoted to research. In the period between 1932 and 1943 I.G. spent slightly less than RM 1bn, averaging an expenditure of rather more than 4.1 percent of (war inflated) average annual gross sales. A significant percentage of these expenditures went into research on products not yet in commercial production, and constant attention was also paid to novel applications of products. Well over 1,000 highly qualified men and women were regularly engaged in research work. In addition, the firm financed research work in many universities and scientific institutions.

Unlike the current run of tech firms with little- or nothing to show but borrowed fortunes for executives and venture capitalists, Farben’s top scientists and engineers were Nobel Prize winners … Haber, Bosch and Bergius; later Otto Diels for chemistry, Gerhard Domagk for medicine. Brilliant as the company was, Farben’s crimes were appalling. Farben and its manufacturing counterparts Vereinigte Stahlwerke, Daimler, Krupp, BMW, Messerschmidt, Rheinmetall, M.A.N., Mauser and the rest were the ‘Military Industrial Complex’ before the term as such existed. The complex’s war against Europe cost the lives of thirty-two millions or more, additional millions were wounded or left homeless. Instead of empire, the war left Germany divided and in ruins. The conventional narrative suggests Farben as an accomplice or pro-forma enabler of the Nazi Reich and its horrors but this is incorrect. Hitler and his gangster cronies were products of Farben no different from polystyrene and printing ink.

Technology is seductive. From the dawn of modernity in 1455, it has offered the chance for those who possess it to gain ascendancy over those who do not. The first public expressions of modernity were both revolutionary and aggressive. The printing press enabled Martin Luther’s reaction against the Catholic Church, the three-masted sailing ship made possible the almost instantaneous conquest of much of the Western Hemisphere by Spain and a handful of adventurers. The press put paid to the Church’s monopoly on information and by doing so ended Rome’s position as mediator of public and private affairs across Europe. The sailing ship took rapacious Europeans to every corner of the world, to pillage what they could, to colonize and enslave as far as the oceans could carry them. The roots of technology are in war and revolution, its branches are crimes and misery, death and ruin; we obsess about the flowers while we choose to endure- or ignore the rest.

Like a wrench or a saw, technology offers leverage: the policies that spring from it are entirely self-referential and self-contained. A saw either cuts or it doesn’t; what happens otherwise is never an issue, what matters is the ‘efficiency’ of the cut. Technology sets its own terms. To the saw everything looks like a piece of wood; analysis is reduced to these terms and none other. The observed purpose of technology to expand itself; it is both ends and means simultaneously, with one justifying and reinforcing the other. Spain’s conquests and Luther’s bid for reform set into motion social and economic events that culminated a century later with the Thirty Years War and the annihilation of a quarter of Europe’s inhabitants. On its own terms, Auschwitz was a very good concentration camp, it was able to murder over a million harmless Europeans and provide industry with a million more as slaves at very low ‘per unit’ cost; with very little fuss. Objections were- and are nothing more than sentimentality; those Jews and Russians were all going to die, anyway.

By way of the internal logic of technology, the most outrageous crimes are nothing other than ordinary, predictable mechanical processes. Technology ‘does’ because it ‘is’, there is are no other reasons, in fact reasoning is never part of the industrial equation; here there is never a why. Like the genie and the bottle, technology cannot be ‘un-invented’, it can only be replaced by newer, more revolutionary and warlike versions, or forgotten or starved of the materials it needs to continue. The failure of technology is that while it offers reach and grasp it cannot provide things that are inherently peaceful and accommodating. It is the same with economics, which produces ‘wealth’ but cannot provide money that is impossible to steal.

Within the version of ‘modern’ that Farben conjured as it trundled along, the firm itself was an unexceptional component as were the materialist anti-philosophy and the baggage of self-driven rationalizations that went along with it. Like gravity in Einstein’s universe, Farben ‘bent’ the space of modernity, adapting everything within it to itself. Whatever was in that space was Farben’s property, to do with what it pleased. This included the humans who were victims of the company as well as the governments that victimized them for the company’s profit. Outside the curve, the firm’s products existed for no other reason other than they did not exist before, what was to be done with them after they were delivered and the warranty ran out was never the company’s business … According to the internal logic of technology — not just Farben’s — the product was- and is always neutral; guns don’t kill people, neither do explosives, nerve gas, cars or atomic bombs, tanks, drones or air-to-surface missiles. Hannah Arendt observed of the blandly innocuous Standard Oil of New York employee Adolf Eichmann:

The trouble with Eichmann was precisely that so many were like him, and that the many were neither perverted nor sadistic, that they were and still are, terribly and terrifyingly normal. From the viewpoint of our legal institutions and of our moral standards of judgment this normality was much more terrifying than all the atrocities put together for it implied – as had been said at Nuremberg over and over again by the defendants and their counsels – that this new type of criminal, who is in actual act hostis generis humani, commits his crime – under circumstances that make it well-nigh impossible for him to know or to feel that he is doing wrong.Eichmann, like Arendt’s ‘others’, was a product … of what-ever branch of industrialization, it does not matter. He was more deadly than some, less so than others. Accompanying Eichmann in the dock was the banality of technology, the dumbest of all automatons; without comprehension or sense; a Golem made of nitrate and rubber hovering both in- and outside good and evil not quite one nor the other, all things being exactly the same. This is the logic and tyranny of the machine, the false idol we have decided it is best for us to live in the center of.

Gerhard Schrader aimed to end world hunger; in the process of developing pesticides he discovered the nerve agent Tabun, that was later produced in large quantities by Farben. The chemical turned out to be difficult to handle and for that reason and for others, it was never deployed. Haber’s ammonia synthesis offered the same benign promise, to feed the hungry. In 1914, Haber without hesitation volunteered his expertise to the Kaiser government, to develop and deploy poison gas during the war, having a personal hand in the first use of chlorine during the Second Battle of Ypres in 1915. “During peacetime a scientist belongs to the world,” said Haber, “during wartime he belongs to his country.” Ammonia synthesis was the foundation of Imperial German firepower, without BASF’s explosive compounds, the German assault on the rest of Europe would not have been possible. Hitler’s war would have been stillborn without the ability of Farben to synthesize motor fuels and rubber — and to obtain essential compounds as well as intelligence from its American partner Standard Oil. The conventional narrative casts Hitler as the convenient villain; that the rest of the German government, its helpful industries and naive populace were dupes. That Hitler was a villain there is no doubt. The narrative one step further makes Farben the industrial villain and that its fleet of partners and lenders, including Brown Brothers Harriman, Standard Oil, Shell Oil, Morgan Bank and the Bank of England were dupes as well. Another step further and the German Schutzstaffel-SS were the evil actors that the Farben executives were taken advantage of; this narrative held longer and was very convenient as scores of Farben executives took high-level management positions within the firms that succeeded Farben: Agfa, BASF, Bayer AG and Hoechst (merged with other companies).

Technology pushes back limits, but cannot eliminate them. It only goes so far, providing some solutions but not all of them. Farben offers a window allowing technology to reveal its shortcomings, it also a means to understand Germany, which to a large degree was a product of the dye firms that were the parent of the IG Farben company.

– All the answers are wrong: the long shadow of Farben.

– Germany, like the United States, emerged from the crucible of war. They also emerged against the same adversary.

– The First and Second European wars were started for the same reason, Germany lost both wars for identical — but different — reasons. Technology gave Germany the chance at success in its wars but technology proved to be irrelevant at the end.