You too can be a winner! (A loser!)

The recent and ongoing drop in oil prices is good for you! (There is a sense of edgy uncertainty that this may not be true.) With lower prices at the pump everyone can rush over to the nearest car dealer and purchase a new, gas-guzzling SUV or giant pickup truck … or fly the family to Disney World in Orlando! This is good for the economy, right? (No, it’s insane!)

We’re all consumers, right? (No, we all work for finance, we are paid whatever we can borrow.)

For the past six months there has been uncertainty (lies) regarding the causes- and effects of reduced prices and the petroleum industry. (Managers are loathe to admit it,) the trend is deflationary with prices being a consequence of above-ground factors that reduce the ability of petroleum consumers to pay … the number-one above ground factor being the high price of petroleum.

Analysts discuss the rousing success (challenges) of the petroleum supply industries; none of them discuss the (abject) failure of consumption as a business endeavor. Because consumption does not earn anything, all returns must be borrowed. The result is an economy dependent upon finance issuing exponentially expanding debt to fund new consumption as well as to retire- and service maturing legacy loans … in the amounts of hundreds of trillions of dollars.

Oil prices are declining because consumers are insolvent! They cannot borrow any more nor can their governments borrow more in their place. Without loans there is insufficient support for higher prices. This is true for all kinds of goods not just petroleum … as well as for credit itself!

The multiyear reflationary efforts on the part of the world’s central bankers (theft of the citizens’ savings) has been undone in a matter of a few days. The price of fuel is embedded in almost every good if only the shipping component. As the fuel price declines, so must asset prices. While the fuel itself cannot be the collateral for finance industry loans, the companies themselves and their properties certainly are. The last few weeks of plunging oil prices have crushed banks’ collateral holdings by 30% and more. Some form of retrenchment (margin call) is indicated … nothing good for the fuel extraction industry.

All the talk of ‘energy boom’ and ‘revolution’ have served only to make us complacent and ignore risks: underway is an oil shock but we do not recognize it. Unlike 1974 when there were gas lines, odd-even days and the hated ‘double-nickel’, the shock in 2014 takes the form of a credit crisis.

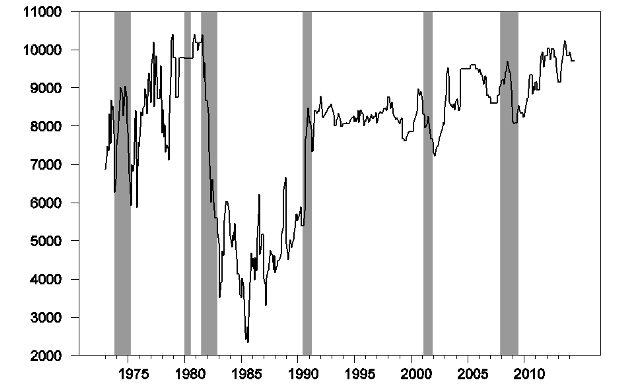

Figure 1: (chart by Euan Mearns with additions). When is a glut not a glut? Consider stock vs. flow: since 2005 conventional crude and condensate extraction has remained more or less flat. Increased output (flow) has come from expensive unconventional sources such as tar sands and ‘shale’ by way of fracking. Our recent, historically high prices are the result of diminished flow rates relative to consumption rate particularly within Asia. Customers there have been willing to pay more (globalization has given them access to Western credit markets).

At the same time, there is inventory buildup (stock) in North American terminals and elsewhere. Oil in the ground isn’t where it’s needed and the distribution infrastructure is insufficient to move it to potential customers. From the standpoint of flow, there is a shortage, from the standpoint of stock, there is a glut … the result of which is another cyclical bust that has tormented oil business in the past, (Byron King, Daily Reckoning):

American Association of Petroleum Geologists (AAPG) has about 30,000 members now, about half the number that it had back in the early 1980s. This is another way of saying that things were booming in the oil biz back then. But many people who worked in the geology business were laid off during the mid- to late-1980s and throughout the 1990s, due to what we look back and call the “oil bust.” From its high price of about $50 per barrel back in 1980 (using the dollars of that era, and it would be over $100 per barrel today in our inflated U.S. dollars), oil crashed in price to near $5 per barrel by the mid-1980s, a 90% fall in price.

The difference between eras: the increased flows in the past were due to new production from Alaska and the North Sea. There were also left-over conservation efforts in the West; China was communist and backward, the developing world was not a significant oil consumer. There was a large inventory build along with increased relative flows. Fast-forward to the present, there are sub-mediocre flows against ballooning worldwide demand and the black-swannish consequences of excess leverage needed to obtain any flows at all.

How high is too high? A lot lower than you think.

Citizens expect oil shocks to be accompanied by very high prices but this can be misleading. The rationing mechanism works identically at high- or low prices. During 2008, prices skyrocketed to a record $147/barrel, consumption fell because customers refused to pay the high price. A few months later price of oil had fallen to $34; another inventory-driven bust.

When customers are broke, even low prices will ration consumption … prices will decline to lower levels. The assumption is that at some (low) price consumption offers an organic return, once the oil price declines sufficiently oil consumption will begin to pay for itself and the economy will return to growth. This assumption is foundationally incorrect: consumption is purely waste, it offers zero return. What matters is credit availability and cost. With world credit leveraged to the solvency of fly-by-night energy companies the availability of credit becomes more and more … iffy.

Economists assume consumption will increase to the upper bound created by available supply … yet this is clearly not so. The upper bound is available credit rather than available fuel. Economists assume there is unlimited credit because interest rates are low, which implies pent-up demand. In reality, low interest rates are the product of central bank bond-buying and rate manipulation. At the finance level there are billions available to firms in the international credit markets, at the same time, customers are unable- or they sensibly refuse to borrow. Within the credit marketplace, customers compete vs. energy companies for funds. At the same time, the amounts the companies must borrow in order to extract fuel, must be borrowed by the customers in their turn to retire the drillers’ loans … plus interest. Drillers can only succeed by ‘out-borrowing’ their customers: the consequence of success is catastrophic! The customers are broke: when companies are unable to lay off their exposure onto their customers, the companies collapse.

Customers can only out-borrow the companies for a little while, they exhaust their own credit along with the resource which increases the funding burden of the companies. Invariably, the customers bankrupt themselves by cannibalizing their capital; this is the fundamental nature of the extract-to-consume regime … that economists don’t seem to grasp.

Energy Commodity Futures

| Commodity | Units | Price | Change | % Change | Contract |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude Oil (WTI) | USD/bbl. | 69.31 | -4.38 | -5.94% | Jan 15 |

| Crude Oil (Brent) | USD/bbl. | 73.17 | +0.59 | +0.81% | Jan 15 |

| RBOB Gasoline | USd/gal. | 192.12 | -11.39 | -5.60% | Dec 14 |

| NYMEX Natural Gas | USD/MMBtu | 4.24 | -0.11 | -2.62% | Jan 15 |

| NYMEX Heating Oil | USd/gal. | 229.32 | -10.33 | -4.31% | Dec 14 |

Precious and Industrial Metals

| Commodity | Units | Price | Change | % Change | Contract |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COMEX Gold | USD/t oz. | 1,185.70 | -11.80 | -0.99% | Feb 15 |

| Gold Spot | USD/t oz. | 1,187.71 | -4.96 | -0.42% | N/A |

| COMEX Silver | USD/t oz. | 16.14 | -0.47 | -2.84% | Mar 15 |

| COMEX Copper | USd/lb. | 289.30 | -6.35 | -2.15% | Mar 15 |

| Platinum Spot | USD/t oz. | 1,214.38 | -3.62 | -0.30% | N/A |

Analysts suggest with a straight face that conventional oil producers such as Saudi Arabia (and Iran) are now engaging in a ‘price war’ vs. the marginal barrel producers in North America. This is part of the narrative that denies the possibility of an energy shortage, (Telegraph):

World on brink of oil price war as OPEC set to keep pumpingAndrew Critchlow

Saudi oil minister suggests Opec oil cartel would keep its production ceiling at 30m barrels per day

Some Opec members want producers outside the cartel to shoulder some of the responsibility for balancing the oil market by essentially cutting their output.

Crude traded in the US fell to as low as

$74 per barrel$69 as traders bet that Opec will allow the price to fall further amid growing signs of a global price war amid producers.“There remains little prospect of any production cut being agreed at [Thursday’s] Opec meeting,” said brokers at Commerzbank. “Opec will merely agree to comply better with the current production target of 30m bpd.

Price war sounds sexy but it is misleading. Nobody in the energy business wants lower prices as diminished output losses cannot be made up with volume. As it is, every energy company is bringing every possible barrel to market …

Figure 2: Saudi oil ‘production’ since 1973, (Oil Price.com, source data by EIA). The Saudis have not increased their output so they have not affected the price. It would be more accurate to accuse shale- and tar sands companies for starting a price war against themselves. Oil analysts can look to the shale gas industry, (Deborah Rogers):

Shale and Wall Street: Was the Decline in Natural Gas Prices Orchestrated?– The price of natural gas has been driven down largely due to severe overproduction in meeting financial analysts’ targets of production growth for share appreciation coupled and exacerbated by imprudent leverage and thus a concomitant need to produce to meet debt service.

– Due to extreme levels of debt, stated proved undeveloped reserves (PUDs) may not have been in compliance with SEC rules at some shale companies because of the threat of collateral default for those operators.

– Industry is demonstrating reticence to engage in further shale investment, abandoning pipeline projects, IPOs and joint venture projects in spite of public rhetoric proclaiming shales to be a panacea for U.S. energy policy.

– Exportation is being pursued for the differential between the domestic and international prices in an effort to shore up ailing balance sheets invested in shale assets.

As with the gas industry, overproduction is relative: unconventional natural gas plays are landlocked, the wells deplete before pipeline distribution networks to new consumers can be installed. Increased gas (stock) fed into legacy distribution systems = crashing natural gas prices. North America’s shale- and syncrude companies’ reserves are landlocked and dependent upon costly railroad distribution to terminals and refineries rather than pipelines.

Inaccessible supply and higher transport costs = discounted well-head price = reduced cash flow. This has left drillers dependent upon Wall Street junk bond financing and increased debt which in turn requires companies to misstate reserves.

As with natural gas, the Ponzi-incentives are for companies to flip acreage in the US and elsewhere. Finance offers more returns than actual physical output. Meanwhile, the debt- straitened companies look to Washington for permission to export (a bailout).

The price war argument is nonsense. Saudi Aramco has been selling 9 million barrels per day @ $108/barrel earning (borrowing) almost a billion dollars per day. At today’s price the same barrels earn roughly $650 million @ $78/barrel. The reduction in revenue implies the Saudis have put onto the market an additional 3 million barrels per day … if they could actually increase output by that much. Otherwise, the Saudis stand to lose hundreds of millions of dollars per day.

Conversely, producers would need to cut production by 3 million barrels in order to push the price back to $105/barrel. This would make sense only if there is an actual excess of supply. Instead, an output cut of that magnitude would cause a shift from an implied shortage (diminished flow relative to consumption) to an actual, physical shortage. So far, the implied shortage has affected customers’ ability to borrow. Further diminishing supply would the crash credit system altogether, this would certainly impact drillers including Saudi Arabia, which is just as dependent upon credit as any driller in the Bakken.

Less credit => less consumption => more of a ‘glut’ => lower prices => less output => less (high-yield) credit for drillers in a vicious cycle.

The claims of energy independence have served to obscure the price signal. Fuel constraints are evidenced by +$100 per barrel prices. Our grim- and nasty ‘auto-habitat’ has been built assuming sub-$20 per barrel into infinity and beyond, any price above that is too high. At the same time: sub- $20 per barrel petroleum = bankruptcy of the entire petroleum industry … along with finance which makes use of petroleum ‘assets’ as collateral.

What is underway is ‘Conservation by Other Means™’. Customers are rendered insolvent faster than lower prices can bail them out … which renders the current state of affairs resistant to management efforts. Central banks cannot reduce the physical costs of drilling even as they manipulate interest rate cost. Subsidies attempt to shift costs from drillers to their already insolvent customers. ‘Marginal Man’ — who sets the falling price for the rest — can be anyone in the world, not necessarily an American; he can be an (ex)motorist in Japan, or a busted tycoon in China.

Any bailout is a temporary reprieve. Accelerating the rate of consumption is stupidly counterproductive; customers are simply ruined, faster. Tepid attempts at mandated conservation will fail from the start: mandated efforts will compound those driven by events. Managers are chasing their tails: the pet theory that at some very-low price, consumption will offer a return. There is no such price! Consumption offers nothing at all but waste.

Conservation mandates only work at levels of consumption far lower than current rates; Euan Mearns’ missing 7 million barrels per day. The alternative solution is to find those missing barrels … too bad, they have already been burned up for fun. The barrels themselves are a moving target as depletion never quits! After 7 million come 8 million … 10 million then 20. We humans needed to make significant program changes starting in the early 1970s but we surrendered to liars and gamblers. Just because we refuse to recognize our oil shock for what it is does not mean it isn’t real.

I wonder how many people will scratch their heads as they’re filling up their tanks this week and wonder how much of a mixed blessing that cheap gas is. They should. They should ask themselves how and why and how much the plummeting gas price is a reflection of the real state of the global economy, and what that says about their futures.— Raúl Ilargi Meijer

Future = less.