Once upon a time, Economic Undertow was concerned about becoming a cliché. Those were the good old days. Now we are diving head first into chaos. What’s going to break, today? Instead of irrelevance, we’re concerned about complete organ collapse and a hideous, stinky death on a (presumably haunted) cruise ship, “I’ve fallen and I can’t get up.”

Yet now the ship moved on!

Beneath the lightning and the Moon

The dead men gave a groan.

Nor spake, nor moved their eyes;

It had been strange, even in a dream,

To have seen those dead men rise.

Yet never a breeze up-blew;

The mariners all ‘gan work the ropes,

Where they were wont to do;

They raised their limbs like lifeless tools—

We were a ghastly crew.

Ghastly, indeed. Confronted with mortality, one escapes into the abstract complaining: ” … it is impossible for anyone to take me seriously. I am beating my head against the wall, others laugh at me or they hate me because I am exposed and easy ‘hate target’. I cannot accomplish anything, I am a boat beating against the current … borne back ceaselessly into ridicule, I am spitting into the wind, up a creek without a paddle, betting the wrong horse. Think of the others who have been pounding that same wall for decades … Nothing changes … the speculators always win, I am a muppet.”

Well … maybe not. How do the markets function when the doors of the cruise ship and everything else are welded shut? Quis weldodiet ipsos weldodes? Who welds the welders? Don’t look at me! I know how to bolt and screw but that’s as far as it goes, I don’t want to be accused of racism! Just let me beat against the current in peace whilst I hide out in this basement. There is enough ‘Made in China’ powdered dog food in here to last for a long, long time.

Trump cheers as Dow breaks 25,000 — for the third time

Trump grew concerned an extended slide could damage his political prospects. He lashed out at Federal Reserve chairman Jerome Powell. And he kept vigilant watch on the markets, using the chart as a barometer of his own standing.

For an instant, the precious Dow reached 26,000. Can ‘Dow 36,000’ be far off? How about ‘Dow 36 million’? The Dow at 3,600 seems just as likely with market prices built on foundations of sand (and bank loans). It’s hard to tell right now whether we’ll have the energy available to run our economy going forward or whether the economy will die a hideous, stinky death all by itself, leaving all that energy tantalizingly out of reach. It’s a race, neck and neck, collapsing supply vs constipating demand, winner loser to be determined.

Economists are puzzled! Oh, for the good ol’ days!” they lament:

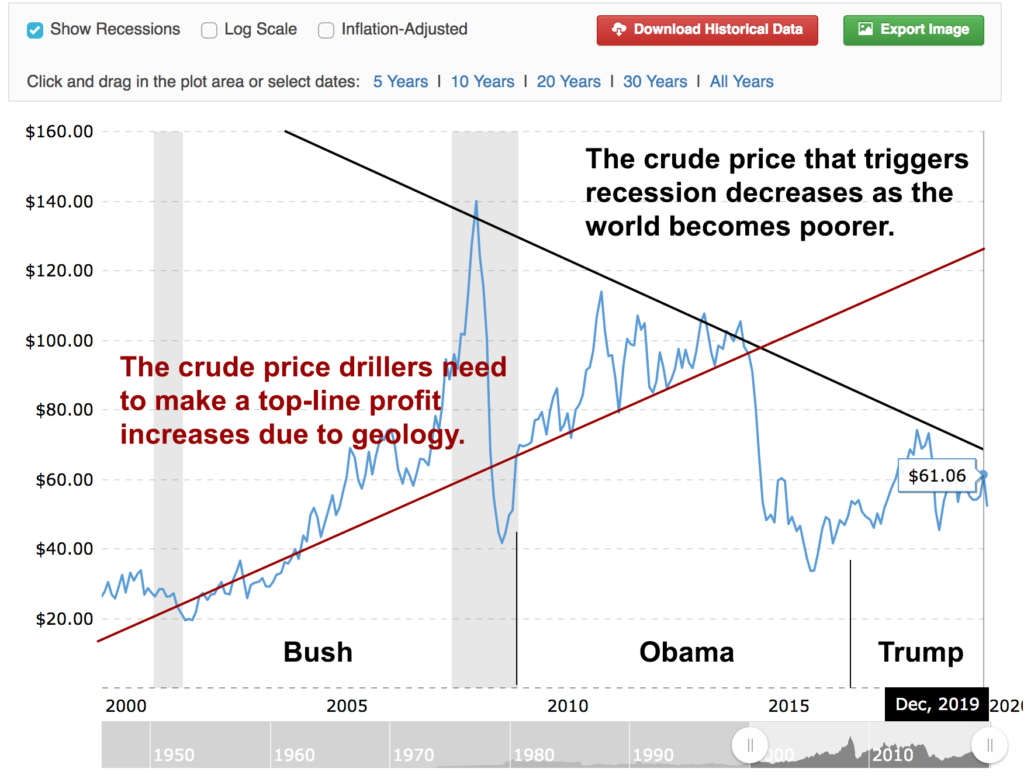

The calendar is not your friend: if trends hold, in five years the deflationary trigger will be less than the 2009 post-crisis low. The oil economy we have become accustomed to since the Roaring Twenties will be kaput. (Macrotrends, click for big).

Note the names across the bottom of this graphic; Bush, Obama, Trump. Bush’s presidency was undone by steadily rising crude prices. World conventional output slowed in 2005 during the middle of his term and spare capacity evaporated. The US invasion of Iraq and that country’s loss of output amplified the price increase. This was good for the drilling industry which needed revenue to invest in developing new reserves; at the same time, rising prices crushed credit. Indeed, banking excesses and fraud were a critical factor causing the 2008 recession but +$4/gallon gasoline prices took the hammer to consumer spending, which accounts for 70% of US GDP.

Obama struggled with high oil prices early on but was assisted by the central bank(s) and longest period of negative real interest rates in US history. During the 2014 ‘Summer of ISIS’, crude prices declined sharply which further boosted the Obama recovery. Trump has been successful insofar as oil prices have remained reasonably low, largely due to the success of the fracking industry. Costly crude would have triggered a recession which would have stranded Trump’s presidency. At $60 and below, Trump, along with Obama, are two of America’s luckiest leaders.

This will not last. The spread between today’s dollar price and the slightly higher trigger price that upsets credit markets is uncomfortably narrow. Onrushing resource depletion and accompanying pauperization reduces the consumers’ ability to meet higher prices: $75 per barrel is too high today, next year $65 will be too high. The following year the too-high price will be $50-55. As the deflationary trigger price declines, it reaches the level where there is little or no crude: we’ve burned through the $20-40 stuff already. Meanwhile the fracking industry struggles with extreme depletion rates and the high cost of new wells, completions and connectivity. Long past the chance of customer revenue supporting them, frackers at this moment are entirely at the mercy of the banks.

What comes after the price allocation regime breaks down? It’s hard to say because it doesn’t happen very often. There are too many contrary trends and feedback loops. Price allocation functions because both drillers and customers use the same dollar (euro, whatever). Driller cost and customer price are always measured on the same scale. Differences between monies of drillers and customers in international trade are ironed out by arbitrage in foreign exchange markets so the real prices wind up on the same scale. Money is an analog for the work done by both drillers and customers, the kinds of work, the per-unit intensity of it are also the same for both. The market allocates the work of the drillers vs. that of consumers by price (access to credit). Allocation choices are decentralized and granular. One way or the other markets run themselves without obvious preferences. Low prices trigger oilfield investment as prices can only go up. High prices trigger profit taking and setting aside further investment as margins shrink.

Low fuel prices are an incentive for consumers to buy bigger vehicles and drive more, to import more goods from overseas, to borrow and spend on houses, vacations and other ‘goods and services’. High oil prices ripple though the entire energy dependent supply chain as a kind of tax; business activity slows and consumers re-calibrate their spending priorities. Price allocation malfunctions because fuel shortages do not make anyone richer; breakdown occurs when even the lowest fuel price is too high, or behaves as the high price triggering a crisis. The endgame is a kind of recessionary black hole: with no price that allows industrial activity at all … including drilling for oil.

The current approach is to flood drillers with loans and hope for the best. Repayment obligations are hived off onto third parties if they can be found. The entire enterprise is lavished with lies and wishful thinking. Bankers having second thoughts about providing loans puts limits on the process. A strategy underway right now in many places is to eliminate direct and indirect subsidies for consumption which generally means taking (unpopular) steps to reduce driving.

A more abstract approach would be to somehow modify the ‘same dollar’ concept, to have one form of currency for drillers and another for consumers. Yet another plan would nationalize the industry with allocation of product by government committee … as was done in the Soviet Union. This last would insure some petroleum is available, nationalization would keep drillers functioning if not solvent. None of the above can change geology as drillers cannot extract oil from places where it is not, or extract oil easily from where it can only be had with difficulty. No form of intervention can create solvency or recover spent resources. Where everything depends on everything else, struggles in the energy sector will have knock on effects in employment and business generally. Propping/rescuing drillers is pointless when the economy does not gain from the use/waste of the fuel; this is the situation we enjoy today, a universe of increasingly self-bankrupting customers.

The dual currency approach is an interesting thought experiment. There are in effect multiple, dollar-denominated ‘currencies’ in circulation within the US today, with one being national currency (those numbers in your bank account) and others including bonds (IOUs) and shares of companies. Both are forms of private money, conceptually at odds with actual ‘money’ as both shares and bonds are assets from the standpoint of their owners whereas money itself is a liability. Today’s asset inflation vs the dollar would be the model for drillers going forward … provided that instruments they would be paid with were also liabilities, issued by some third party beside the government* or the drillers themselves and separated somehow from dollar credit, what all US assets are a proxy for.

Perhaps a commodity exchange could produce a (crypto-) currency that would denominate drilling activity independent of dollar pricing. The work represented by the driller money would be different (worth more) than the work of consumers. Even if the drillers are underwater in dollar terms, they would be solvent in their own currency.

This seems simple enough …

The incentives to run a carry trade — to arbitrage between the driller money and the consumer dollars — would be overpowering and contradictory. Arbitrageurs could simultaneously sell the expensive ‘driller money’ and buy the cheaper dollars to bring the two in line with each other (to reflect reality). The arbitrage process could also run in reverse, traders swapping (cheaper) dollars at whatever price to capture driller-money value (in petroleum). Driller money would have to be worth more than ordinary dollars or the scheme would be pointless. Arbitrage or not, the economy would soon be confronted with the same black hole outcome as doing nothing. Drillers currently offer both shares and IOUs: these offerings reflect (presence or absence of) economic efficiency: many are unfortunate companies poised at the edge of default, whose shares are worth little and whose bonds are junk. Third party offerings along the same line could reflect the same economic dis-efficiencies otherwise they would be fraudulent. Frauds or not, they would be subject to speculative attack. Keep in mind, overseas exporters with their own currencies are also subject to the same black hole outcome. The problem is the customers are broke, their ‘broke-ness’ is ruinous to the drillers regardless of what the drillers do or how solvent they appear out of context.

Any inflationary outcome would result in energy starvation as in ‘Brand X’ countries like Turkey or Argentina. The inflationary dollar would decline in worth, constraining imports. There would be the contagion effects on world trade as that inflationary dollar would throttle business and finance activity, unravel carry trades and upend swaps markets: ironically, inflation itself would become deflationary.

Deflation would see the dollar throwing off its function as a unit- or measure of worth and becoming a thing of value in and of itself; a proxy for increasingly scarce non-renewable capital. This differs from today’s dollar as proxy for the capital destruction process. The tendency is always to hoard value (dollars) and turn away from what is valueless (industrial goods and services). Gaining and holding money would become the business of the country as it was in the West in the 1930s under the gold standard, hard currency being seen as more valuable than any bit of manufactured junk that could be had for it. The Great Depression only retreated when countries abandoned gold, when money shed its value and became a liability relative to manufactured goods, something to be gotten rid of as fast as possible..

Direct government intervention would be the least popular but is actually most likely. Price allocation breakdown means we are too poor to afford oil at any price. Allocation will take place directly without markets. In the drilling industry, nationalization is the rule rather than the exception, the bulk of the world’s petroleum resources are owned- and extracted by governments rather than by private firms. Nationalization in the United States would likely occur after the breakdown of price allocation although some other external trigger such as a pandemic is possible. Nationalization would be accompanied by hard rationing. Being too poor to import and with money dear, Americans would be limited to reserves found within our own borders. To make these last, output could only be a fraction of what is available, today. This would be the end of happy motoring, perhaps all motoring along with the reduction of overseas shipping and air travel. If authorities are wise, agriculture, emergency services, some military and rail transport would have access to fuel. More likely, fuel would be allocated to the well-connected supporters of newly empowered political bosses to sell on black markets. Other claims would follow along as best they could, to be entertained or not arbitrarily, in- or out of some order, then chaotic and violent disorder.

The underlying problem has rarely been inadequate supply, instead, it is consumption does not offer returns to consumers themselves, only pleasure-seeking ‘utility’. We have nothing to show for the resources already squandered but enormous debts, a despoiled landscape and polluting gases circling overhead like angry gods looking to smash us.

And smashing they are. We never were as good as we thought we were, we know enough to get ourselves into trouble but not enough to escape it. Luck is elusive: fires and floods, and the inevitability of greater floods, heat waves and droughts, war and the threats of war, Out of China comes the Coronavirus of which there are as many (frightening) rumors as (also frightening) facts. Beyond argument is the likelihood a large and critical fraction of world business activity will be quarantined by panicked authorities along with human sufferers. There are also the plagues of swine- and avian respiratory illnesses that has killed millions of livestock. There is more, always more: famines and genocides. Our governments are flailing under the strain of resource depletion with uprisings everywhere and a widespread inability of our betters to understand what sort of brain fever has its grip on us. It is us; our prosperity we’ve forged into an armor suit of arrogance and insufferability. Here is only the beginning of the beginning, our dance with fate is at the first turning. We’ve made a stupendous mess of everything in the most frightful and thoughtless manner. Now we are living out our handiwork …

From the fiends, that plague thee thus!—

Why look’st thou so?- ‘With my cross-bow

I shot the albatross.’

“I dunno … it seemed like a good idea at the time.”

* The government issuing any kind of driller money would in effect nationalize the industry.