Be careful of what you wish for, you might get it.

— Proverb

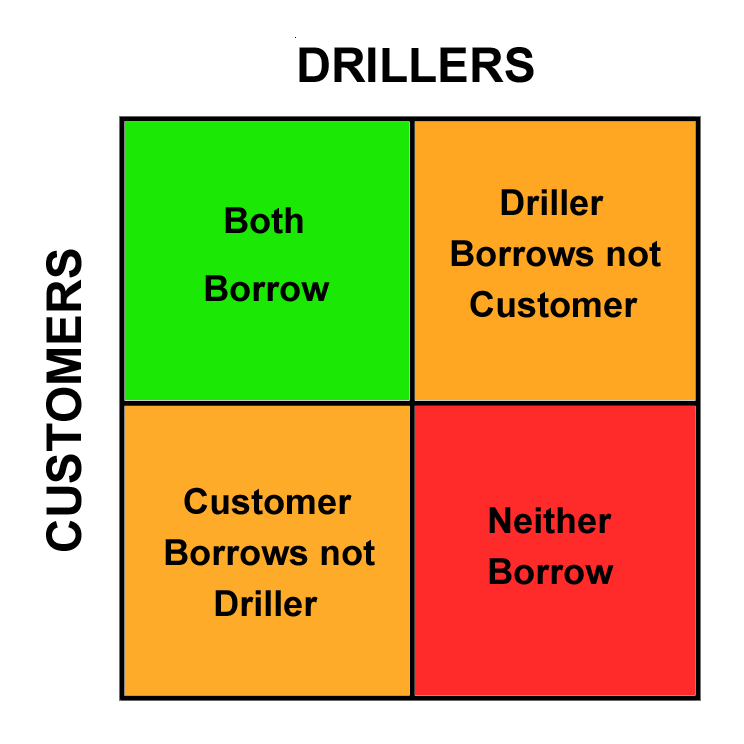

Figure 1: Triangle of utility function by rational agents; by TFC Charts, (click on for big). In a cash economy the inability to afford crude oil would manifest itself as the steady decline of ‘too high prices’. Our economy is built around structured finance; once credit structures are undermined they collapse.

There is a ‘perfect storm’ underway; of insolvent customers, over-stressed finance, willful ignorance on the part of the establishment and denial. Both commodity prices and US Treasury yields are indicating another recession. Customers and drillers are asking how low will fuel prices go and how long will they stay there?

Fund manager Jeff Gundlach responds that no one will know until they stop falling. “That answer isn’t meant to be cute,” he says. “When you have a market that showed extraordinary stability for five years — trading consistently at $90 [a barrel] or above — undergo a catastrophic crash like this one, prices usually go down a lot harder and stay down a lot longer than people think is possible.”

Because modern ‘labor’ is waste, the customer must borrow … or some firm or institution must borrow for him. Workers have been able to gain greater amounts in wages in the past when fuel was less costly: wages are credit, high wages represent the historical productivity of credit. Prices cannot rise further because the ability of customers to earn (borrow) is constrained by (relatively) high crude prices, diminishing the productivity of credit.

There are two sets of borrowers: customers and drillers. Both need to borrow to gain fuel. The borrowing requirements of the driller increase over time because he is constrained by geology while the customer is limited only by access to credit and to wasting infrastructure. At the same time, the customer must take on the drillers’ debts by bidding for- and buying fuel. The relationship between the sets of borrowers conforms to simple game theory:

Figure 2: Energy relationships in 1998 and prior, drillers and customers each borrowed or didn’t borrow. Not borrowing by both meant no economy and no petroleum produced which obviously did not occur. Both customers and drillers chose to borrow: drillers added to excess petroleum capacity making fuel more affordable. Customer borrowing became added gross domestic product (GDP). This amplified driller borrowing which made even more crude available at still lower prices! During this period, there was no need to allocate between drillers or customers.

From 1998 onward, the productivity of each dollar invested in crude production over time has continually declined. This is the basis for the Undertow argument that Peak Oil occurred in 1998: that the baleful economic effects predicted to occur after Peak Oil started to be felt in 2000. To gain more crude oil drillers were required to add more wells, each well was more costly than the last, each well offered less crude oil than previous wells: the effect of this effort has been felt by oil consumers who have had to compete with the drillers for each dollar of credit.

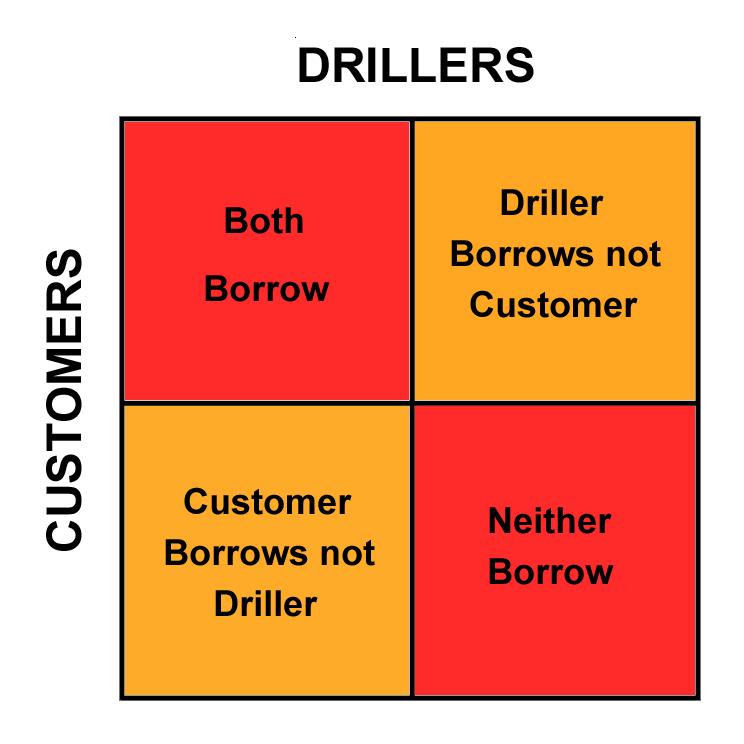

Figure 3: Post-1998, brutal new game theory: mutually assured (demand) destruction!

Borrowing by customers returns less GDP, borrowing by drillers returns less crude. When drillers borrow alongside their customers, they cannot keep pace because demand is easier to create than supply: automobiles are more easily had than new oil fields. Attempting to add to GDP (borrowing by customers) increases demand for crude which exhausts inexpensive fields faster, this in turn adds to the credit requirements of the drillers, returns diminish and borrowing costs pyramid. The outcome is the same as when neither drillers nor customers borrow, there is no economy, all are bankrupted by costs.

The alternative is for the customer to borrow at the expense of the driller or the other way around. Both customer and driller now compete for the same credit dollar: the customers’ need for funds is absolute, they must borrow more than drillers or they cannot buy anything and there is no GDP growth. Drillers need for funds is absolute, they must borrow more than the customers otherwise there is less fuel for the customers.

Unlike finance, petroleum is a bottom up business. At the end of the day every drop of oil/refined product has to be bought by a customer. Because there is so little return on what he does with the product he must borrow to pay for his purchase. He borrows, his boss borrows, his government borrows, his nation borrows other countries’ money (borrow by way of foreign exchange). Our economies are nothing more than interconnected daisy-chains of loans. Over time these chains have grown to amount to hundreds of trillions of dollars. As debt piles up it can only be serviced and retired by taking on more loans.

Even as the US makes less in the way of physical goods like clothing, shoes, washing machines or table radios, its Wall Street firms manufacture the bulk of the world’s credit; this is needed to substitute for absent monetary returns for just about everything else. Driving a car does not pay for the car (times- 1 billion cars), nor does it pay for the fuel, the roads, the massive governments including costly military endeavors, nor does driving pay for the ordinary costs of finance … risk premia and interest carry, which have ballooned exponentially. Other than for the smallest handful of customers — transit, construction, farming, delivery, emergency/first responder — customer use of fossil fuels and other capital is non-remunerative waste, for pleasure-fun, convenience, status, etc. The fashionable wasting processes — including fuel extraction industries — are collateral for more and more loans.

The simplest of models is all that is required to see where this ends up: subtract the costs of petroleum extraction from the small use that provides an actual return. This difference is the price that the economy can actually afford to pay without the use of credit. With extraction costs rising — which cannot be denied by anyone — and with actual returns being very small, the output of the model looks to be a negative number. What that implies is the price of fuel will fall all the way to zero with nothing to be done in the way of ‘administrative adjustments’ to alter this outcome.

Managers appear to be helpless because they have thrown everything at the economy but the kitchen sink: key men have been propped, banks bailed out; interest rates across all maturities are near zero, real rates are negative- or nearly so. Governments around the world are at the borrowing limit, there is little in the way of good collateral remaining for central banks to take on as security for new loans. Conventional marketplace fixes such as debt jubilees/write-offs, re-distribution, bailouts, stimulus, austerity policies, monetary easing, etc. are efforts to reclaim resource capital that no longer exists. Remedies accelerate unraveling process by increasing gross debt (claims against capital) while exposing remaining capital to consumption at higher rates. The capital ‘pie’ cannot be created anew or redivided, only a new and much smaller pie is to be had and carefully tended. Our smaller pie of non-renewable resources is what we have to make use of, to last us and the rest of the world’s creatures until the end of humanity.

Managers certainly understand but refuse to acknowledge that resource extraction over extended periods has consequences. Nations, regions, individuals and firms have experienced temporary shortages of fuel, credit and other resources in the past due to wars, droughts and other disruptions. A grand civilization at the height of its power has not exhausted its prime mover since the Romans stripped their empire of firewood beginning in the first century BCE, precipitating its decline.

Energy Commodity Futures

| Commodity | Units | Price | Change | % Change | Contract |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude Oil (WTI) | USD/bbl. | 48.82 | +0.89 | +1.86% | Feb 15 |

| Crude Oil (Brent) | USD/bbl. | 51.18 | +0.08 | +0.16% | Feb 15 |

| RBOB Gasoline | USd/gal. | 133.95 | -1.48 | -1.09% | Feb 15 |

| NYMEX Natural Gas | USD/MMBtu | 2.88 | -0.06 | -1.97% | Feb 15 |

| NYMEX Heating Oil | USd/gal. | 170.08 | -2.54 | -1.47% | Feb 15 |

Precious and Industrial Metals

| Commodity | Units | Price | Change | % Change | Contract |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COMEX Gold | USD/t oz. | 1,212.20 | -7.20 | -0.59% | Feb 15 |

| Gold Spot | USD/t oz. | 1,215.30 | -3.28 | -0.27% | N/A |

| COMEX Silver | USD/t oz. | 16.54 | -0.10 | -0.58% | Mar 15 |

| COMEX Copper | USd/lb. | 276.15 | -0.55 | -0.20% | Mar 15 |

| Platinum Spot | USD/t oz. | 1,221.25 | +1.81 | +0.15% | N/A |

Graphic by Bloomberg:

– Energy deflation is when increased fuel demand relative to supply does not cause prices to rise but undermines the ability of consumers to meet the price even as it falls. This is what is taking place wherever one makes an effort to look. A component of the onrushing crash is the easy money policy in Japan/Abenomics added to the other bits of monetary stimulus in other currency regions. It isn’t the end of the policy that is causing the crash but the policy itself as purchasing power flows from customers toward big business (drillers) and lenders. More easing => more purchasing power diversion => less credit => lower fuel price => more bankruptcies => more credit distress => more easing in a vicious cycle. What drives the process is the foolishness of central bankers who do not understand the consequences of their (obsolete) policies.

– Drillers rely on loans, lease flipping and share offers than upon revenue from sales, this is largely because of higher costs which would otherwise leave them underwater. The fracking boom and other expensive second-generation extraction regimes are as dependent upon structured finance as the real estate plungers were in the US beginning in 2002. The ‘waterfall’ decline in oil prices suggest that financing structures are coming undone. Finance innovations such as CLOs disguise risk and shuffle it around rather than eliminating it. When risks ultimately emerge they overwhelm the structures intended to manage them; hedging strategies rebound against hedgers, those that can race for the exits, the rest suffer severe losses as the prices collapse.

– It is possible that energy companies’ hedging strategies are contributing to the ongoing crash the same way ‘portfolio insurance’ abetted the stock market swan-dive in 1987: that is, sales of contracts in futures markets in order to hedge finance losses, elsewhere.

Because the leverage structures cannot simply reconfigure themselves after they collapse, oil prices cannot ‘bounce back’; a replacement credit regime must take the place of the broken system. Shadow-banking was vaporized by the housing crash in 2008; it was imperfectly replaced by a generalized credit expansion by way of Treasury borrowing along with central bank moral hazard: both of these offer diminished- or negative returns which is why this regime looks to be failing now … with nothing to replace it.

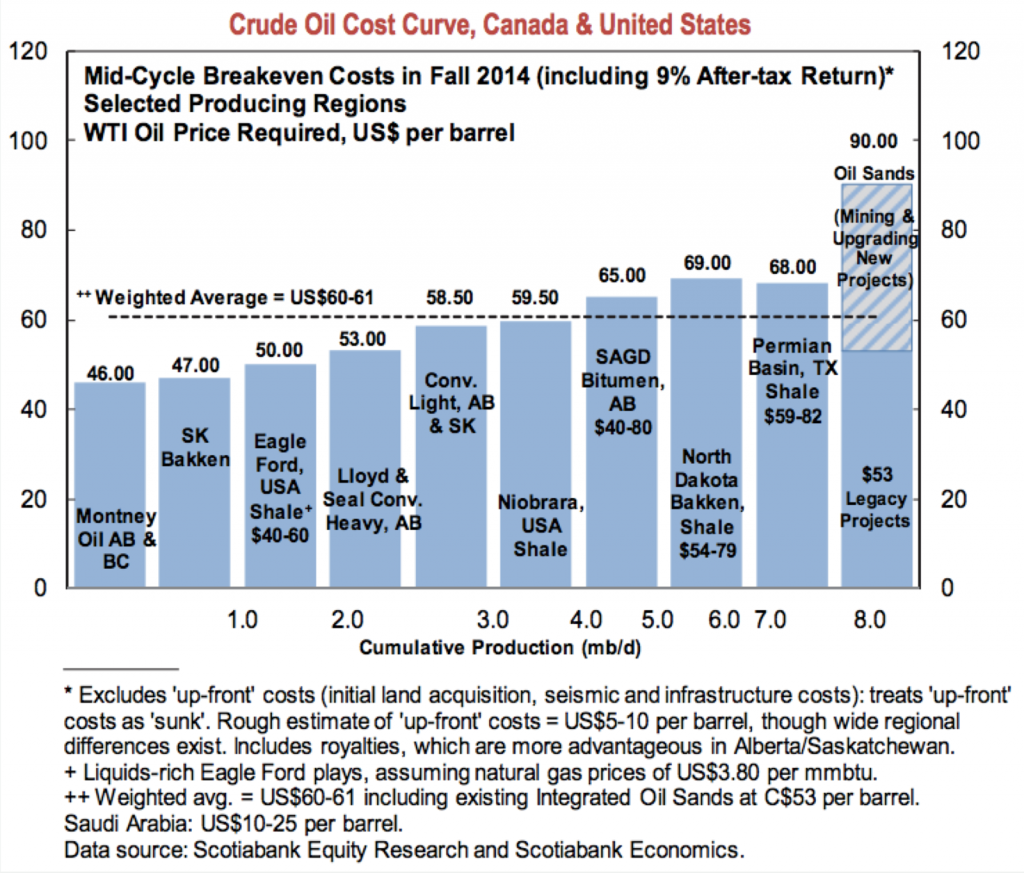

– Every dollar of price decline cuts output. Any oil that would be available at the higher price is removed from the market when prices fall. As the price declines, the only fuel available is that which costs that amount to extract or less:

Figure 4: Prices for selected petroleum-fuel plays from Scotiabank (click on for big). Sub-$50/barrel prices looks to shut in as much as 3 million barrels per day, a cutback equal to a third of Saudi Arabia’s output. Price decline is the industry’s fuel cutback mechanism, no other actions by drillers, nations or organizations such as OPEC are needed. This is another component of energy deflation; the only issue is how cuts will affect the customers.

Fuel cutbacks do not occur overnight: contracts between drillers and refiners remain in force and there is inventory in storage. Drillers will borrow as long as they are able to, hoping for a miracle. As the contracts are satisfied and inventories depleted uneconomical supplies will be shut in leaving what remains of lower-cost fuels. Under the circumstances, this remaining supply would likely be hoarded as it would be worth more than other possible uses.

– ‘Dollar Preference’, from the Debtonomics series is the convergence between the value of oil capital and the dollars that are exchanged for it. Fuel by itself is worth more than the real-world enterprises that waste it regardless of what means are used to adjust the price. Enterprises earn nothing on their own and are essentially worthless. They exist solely to borrow, gaining- and making use of credit is their primary product: other goods and services are intended to justify credit issuance in ever-increasing amounts. Part of this stream becomes the property of well-positioned ‘entrepreneurs’: enormous unearned borrowed profits are what drives the system. When debt = wealth, there is an incentive to take on as much debt as possible, keep what you can for yourself and to shift the retirement- and servicing burdens onto others.

Management is paralyzed by the internal contradictions of the debtonomy. We cannot get rid of (some of) the debt without getting rid of (all of) the wealth. We cannot get rid of the debt because we would need to take on even more ruinous debts immediately afterward to keep vital services operating such as water supply. If we get rid of the debts the prices will fall leaving debt-tending establishments without investment funds. Our debts cannot be rationalized, the absence of debts cannot be tolerated. The debt system is rule-bound. Debts that were increased because of favorable rules face annihilation because of the same rules, changing the rules threatens debt elsewhere. Nowhere are there real returns to service the debts much less retire them. Nothing remains but the arm-waving of central bankers. As the banks create more debt (against their own accounts), their efforts are felt at the gasoline pump which adversely affects debt service.

The debtonomy is Gresham’s Law applied (on purpose?) to goods and services; the bad drives out the good, the worst drives out everything else. The ‘bad’ enterprises which groan under massive obligations possess a competitive advantage over the virtuous ones that earn without taking any debts on. Debts are artificial earnings which are used to price the good companies out of business then engulf their markets. The final step is for the debt-gorged monstrosities to fall bankrupt due to their massive size, these are then bailed out by the even-more bankrupt sovereigns.

Energy guru Chris Cook uses the term ‘Upper Bound’ to describe the fuel price level that constrains economic activity. The price rise can be caused by increases in the available credit or by a decrease in the amount of available fuel relative to the current credit supply.

What happens at the other end of the bound? If the upper is tough to deal with the lower is good, right?

It goes without saying that the crude is vital. The ‘Business of debtonomy is debt’ but the presumption is of fuel waste for a ‘higher purpose’ which is embodied within our progress narrative. Without continuous waste debt becomes an unsupportable dead weight on all enterprises. Here is the confusion over the effects of fuel shortages on economies: ending waste is thrift, it is economical to do so. Ending waste is fatal to our debtonomy which needs the waste to justify its existence: economic thrift is an un-debtonomic catastrophe.

It is different this time: the decline of the fuel price means there is less fuel made available to waste, that the high cost variety is off the market. Low priced fuel means there are no businesses with credit. Lower price fuel is worth more than any enterprise that uses it, the lowest possible price means the industrial scale fuel waste enterprises are ruined, both producers and consumers.

The decrease in the dollar price of crude is ipso facto marketplace repricing more valuable dollars. The lower bound is where dollars become a proxy for crude and are hoarded. At that point all things are discounted to the dollar because the dollar traded for crude is more favorable than a trade of anything else for crude, that includes other currencies as well as dollar-denominated credit.

Just like the upper bound where a dollar is worth less with each increase in fuel price, the lower bound represents a dollar that is worth more because of its price in crude. A low crude price has a dollar that is worth too much to be used for carry trades or interest rate arbitrage which is the primary business activity within the debtonomy.

The lower bound is reached when currencies are discounted to dollars. A reason for this is the universality of the dollar. Because the US has been for so long the world’s consumer of last resort, goods that were sold for dollars in the US are tradeable everywhere in the world for the same dollars. The dollar purchases of the past and dollars in circulation now are the purchasing power of the future.

The dollar is also the world’s reserve currency, dollars being used to settle trade accounts. The trade of goods between countries whose currencies are illiquid may have foreign exchange risks that exceed the profit to be had by way of the trade. The exchange of the currencies for dollars bypasses the risks because the universal dollar is a liquid, stable substitute for third-party currencies. Reserve status of the dollar and its universality provide leverage that other currencies do not possess.

The trade of dollars for crude sets the worth of the dollars rather than do the central bank(s), this trade takes place millions of time a day at gasoline stations all over the world.

Motorists determine the worth of money; this strands the central banks. In their futile attempts to assert some sort of relevance the central bankers and policy makers manipulate interest rates, pillage bank depositors, ignore moral hazard and bail out their friends. They seek to reduce the worth of money relative to other money. In doing so the bank surrenders what small fragments of policy-making ability which remain to it. Bankers can set interest rates to zero but no further, can whitewash the accumulation of risk but cannot set the money price of petroleum except to make it unaffordable which precipitates the catastrophe the bankers are desperate to prevent.

The catastrophe the bankers are desperate to prevent is the destruction of demand, where fuel falls into strong hands and dollars are hoarded because they are proxies for scarce petroleum, energy in-hand.

For this reason, dollar preference effects net energy which is consumption taking place in energy producing countries. This consumption is entirely dependent upon consumer goods that are affordable because of high fuel prices. Russians produce automobiles and other Russians buy them because the national oil companies are able to sell their product for +$100 per barrel. The price subsidizes both Russia’s debts and her energy waste. Ditto for the energy consumption of Saudi Arabia, Iran, US, Kuwait, Iraq and all the rest. When energy prices fall so will energy consumption in producer countries if only because lower priced oil production will be too scarce to waste.

At $10 per barrel, Russia will produce very little fuel, only from the cheapest and easiest to produce fields and will trade it for hard currency only. Domestic sales will take place in black markets for dollars or gold, few Russians will have dollars and those that do will hold onto them for emergencies. Hard currency earned by the export of crude will be used to buy food and medicine, not imported luxury automobiles and television sets.

Diminished net exports are dependent on high prices which are in turn dependent upon constantly expanding credit. When cash is preferred over credit there is nothing to support the high prices or fuel waste. Cash is hoarded and credit is evaporated.

The end-game of dollar preference is crude-driven dollar deflation as took place in the US in 1933. Dollars were held as ‘gold in hand’ and business in the country was the buying and selling of currency to obtain gold which was necessary to settle contracts. The deflationary impulse was ended when the world’s governments ended specie and fixed convertibility, cutting the currency links to gold. The need will be for the US to end the dollar’s convertibility to crude, to go ‘off crude’ as countries went ‘off gold’. The alternative is for dollars to vanish from circulation and cease to be a medium of exchange. Local currencies emerging in the dollar’s place will be of little use in the obtain of fuel imports, the country will be limited to the petroleum that can be sustainably produced on its own soil.

Dollar preference is self-limiting. Dollar preference in 2015 is the demise of the euro, yen, ruble, peso, real … their unraveling illuminates widespread mismanagement. Doubts about currency regimes take root. The differences between the euro, yen, sterling, yuan and dollar currencies are minuscule. Euro debts are no different from the debts of the others, European waste is no different from the waste of others. There is nothing special about the dollar other than a military machine that is debt-dependent and failure-prone. Dollar preference condemns the rest which starts the clock on the ultimate death of the dollar.