Anyone paying attention cannot be surprised by economic distress being felt around the globe … we are all reaching the neck of the funnel, the farthest corner of the box we have built for ourselves out of foolish contradictions and hoped-for perpetual motion machines. There are multiple ways out of the box but we cannot bring ourselves to turn around and step away, to turn loose of our toys that drag us off the edge toward oblivion. Instead, we press ever more tightly into the corner, hoping an escape hatch will materialize by magic.

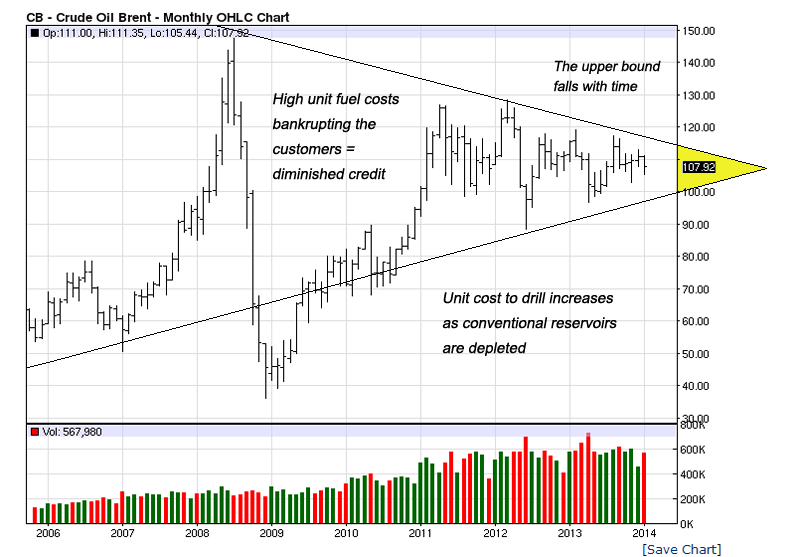

Figure 1: The World-famous Triangle of Doom: continuous Brent Crude futures price up to the end of January, 2014, chart by Commodities Charts.com. Click on chart for big. The upper bound declines along with creditworthiness. The cost of fuel production increases due to geology and the increased difficulty in gaining fuel to replace that which we have wasted. $110 per barrel appears to be the new upper bound; as the Brent price neared that level a host of countries’ economies began to vomit.

The declining trend is what customers can afford to pay: the advancing trend is the crude oil price required by drillers to remain in business. Soon enough, the price required by drillers will be unaffordable, the outcome will be shortages as first the highest- cost supplies are shut in. Shortages will further affect customers who will purchase less fuel pressing on prices in a vicious cycle.

Our unhappy date with destiny can only be ahead of us as long as nothing important breaks and the managers avoid errors. Keep in mind, any shortages that occur because fuel is unaffordable … will be permanent. One cannot dig oneself out of a hole, having constrained fuel supplies does not make countries richer or more fuel available.

It is axiomatic when fuel prices are too high there are adverse economic consequences which cause prices to decline. Consequences have arrived it is reasonable to propose fuel prices are too high, they are set to decline. Prices have been high for a very long period, for the wealthy and ambitious, at least ten years. Organic economic growth has been impossible due to fuel prices allocating funds away from non-fuel sectors, what has stood in for growth has been the ‘wealth-effect’ of expanding credit. This last is coming to an end because credit has also become unaffordable. Welcome to the energy crisis in 2014; there are no gas lines or ‘odd-even days’, there is no hated ‘double nickel’. Instead, credit is rationed and countries are left with worthless money that cannot be swapped for fuel; conservation by other means.

It is possible that the model is too conservative, that we have already reached the end of the affordability road. That the effect of high prices is felt at a level that is lower than the trend would indicate. It is also possible the ‘too-high’ price is too low at the same time; so that producers such as Russia and Mexico are unable to meet expenses.

Meanwhile, the managers are not error-free. The new regime of monetary tightening on the part of US and China looks to be a serious misstep, (Ambrose Evans-Pritchard, Telegraph UK):

World risks deflationary shock as BRICS puncture credit bubblesHalf the world economy is one accident away from a deflation trap. The International Monetary Fund says the probability may now be as high as 20pc.

It is a remarkable state of affairs that the G2 monetary superpowers – the US and China – should both be tightening into such a 20pc risk, though no doubt they have concluded that asset bubbles are becoming an even bigger danger.

“We need to be extremely vigilant,” said the IMF’s Christine Lagarde in Davos. “The deflation risk is what would occur if there was a shock to those economies now at low inflation rates, way below target. I don’t think anyone can dispute that in the eurozone, inflation is way below target.”

It is not hard to imagine what that shock might be. It is already before us as Turkey, India and South Africa all slam on the brakes, forced to defend their currencies as global liquidity drains away.

The World Bank warns in its latest report – Capital Flows and Risks in Developing Countries – that the withdrawal of stimulus by the US Federal Reserve could throw a “curve ball” at the international system.

The tightening error is perhaps unavoidable. The energy problem cannot be solved by substitution, by swapping credit for energy; the credit has ballooned to become its own problem. The government strategy of propping key men and hoping for the best turns out to have a limited shelf-life. The personal- and business strategy of relying on public relations in place of facing reality and taking the necessary, albeit painful steps to either adjust or find alternative business models has also failed. While these are not errors per se, they are longer term expedients whose consequences have arrived sooner than their architects intended.

Call this diminished returns on expedients.

While currency problems have to a large degree materialized since the beginning of the year, the forces behind the problems have been building for a long time. All of the countries in trouble today are key men that the corporate- and government establishments have done as much as possible to prop up. Wall Street has lent trillions of dollars overseas since 2008 to purchase GDP growth as if this abstraction is a thing that has some effect on the physical world. It does have an effect and that is to reduce the world further. Funds have become collateral for trillions- more loans in the currencies in question. The problem is that none of the so-called investments turn out to be remunerative, any more so than prior rounds of investments. Managers have been chasing their tails, throwing not-quite good money after terrible.

It can be said, “In the long run we are all dead”; reality provides its own proofs, we can see that the increase in debt accompanies the so-called advance of progress. Common bookkeeping illustrates the absolute requirement for ‘capital’ (borrowed money) in order to advance industrial works of every kind. The assumption on the part of others is that an industry can turn around ‘at some point’ and begin to pay its own way … which industry cannot do, this is simple thermodynamics.

Rather, the process of borrowing — by itself — is become collateral for further rounds of loans, each round larger than the last. Loans are never ‘paid off’ (finance level loans are impossible to repay even with 10% growth), the growth becomes a form of permission for more loans, not the means of repayment. Eventually the costs of lending become unbearable, which is one of the burdens we are staggering under right now.

Instead there is the rolling default as the worth of funds used to repay become less than the worth of funds lent. The joke is on the borrower because his loan cost the lender nothing yet he must find circulating money and hand it over to his lender. The cost of obtaining circulating money rather than interest is the real burden associated with debt. There is far less circulating money than there are debts, the cost is then simply supply-and-demand rather than the fixed percentage of interest.

Buried within this tangled web of contradictions is the fallacy of currency debasement which will be dealt with elsewhere.

Once upon a time, a petrodollar was one held by an overseas oil producer gained from the sale of his product. The petrodollar of the 1970s and 80’s was a problem: what to do with all of them?

The (petro)dollar is now is the preferred medium of exchange for petroleum … along with euros, yen and sterling … as opposed to other, lesser currencies.

The reason is because these media are available in needed amounts, and are freely exchangeable in foreign exchange markets … so far. The lesser currencies, much less so.

Since World War Two, money — including dollars, yen, euros, etc. — has been a proxy for commerce. In this context, commerce is deemed to be worth more than money so there is incentive for ‘customers’ to trade money they hold for goods and services as quickly as possible.

Almost everything the establishment has attempted since the Lehman crisis has been to reinforce this theme of commerce being worth more than money. Now this regime is falling apart.

Meanwhile, under the establishments’ noses, money is becoming a proxy for petroleum. In that context, petroleum is observed as being worth more than commerce; this is because commerce is revealing itself to be unproductive/auto-destructive. The ‘money choice’ is being made starting within the marginal economies around the world: money is less about commerce and more the capital inputs that are precursors for commerce … indeed, tools necessary for survival.

If money as a proxy for commerce, customers rapidly trade it for goods and services. When money becomes a proxy for petroleum, customers hold money because it becomes the last, best chance to gain goods that are certain to be scarce in the future. Here, the dollar becomes a hard currency, much like 1930s dollar, redeemable for gold.

Right not the ‘price’ of dollars and other currencies is set — not by central bankers or by government fiat — but by millions of motorists using dollars in exchange for gasoline in filling stations all over the world 24/7. Here, other, lesser currencies are proxies for dollars; again, some moreso than others.

It’s a very short distance from exchangeability to redeemability. Making that step is what is underway right now. In the early 1930s, the economy of the developed world shifted from a preference for commerce toward one of holding gold. Gold became the last, best chance to get a roof overhead or something to eat. The world’s economy became gold arbitrage and little else; contracts, currencies and credit were deployed as blunt instruments in a deterministic contest to gain gold. In 3 short years business, banking and to some degree agriculture collapsed.

Preference takes place in people’s minds, it effects how they perceive relative worth and what their own conditions allow. In the 1930s, the US and other countries severed the gold-money connection, they ‘went off gold’. Today, we face ‘petroleum arbitrage’ and the use of blunt instruments to gain fuel the same way our hapless ancestors struggled to gain gold. This is what we see in southern Europe, in Middle East and northern Africa and across Central- and South America. It is a pitiless contest, the losers are deprived of imported resources, those with resources are obliged to part with them cheaply.

As then, our challenge is to ‘go off petroleum’, we do so or else. We must grasp the nettle and court an industrial depression in order to avoid the alternative, an endless Greater Depression that is right now unfolding at our feet.

A Federal District Court judge recently allowed a defamation suit by climate scientist Michael Mann to proceed against the periodical National Review and a carbon shill Mark Steyn:

Climate scientist’s lawsuit could wipe out conservative National Review magazineDavid Ferguson

The National Review magazine, longstanding house news organ of the establishment right, is facing a lawsuit that could shutter the publication permanently. According to The Week, a suit by a climate scientist threatens to bankrupt the already financially shaky publication and its website, the National Review Online (NRO).

Scientist Michael Mann is suing the Review over statements made by Canadian right-wing polemicist and occasional radio stand-in for Rush Limbaugh, Mark Steyn. Steyn was writing on the topic of climate change when he accused Mann of falsifying data and perpetuating intellectual fraud through his research.

Steyn went on to quote paid anti-climate science operative Rand Simberg — an employee of the right-wing think tank the Competitive Enterprise Institute — who compared Mann to Penn State’s convicted child molester Jerry Sandusky.

Mann, Simberg said, is “the Jerry Sandusky of climate science, except that instead of molesting children, he has molested and tortured data.”

Mann sued for defamation. Steyn and the Review vowed to fight the suit, given that defamation is notoriously difficult to prove in court.

“My advice to poor Michael is to go away and bother someone else,” said Review editor Rich Lowry. “If he doesn’t have the good sense to do that, we look forward to teaching him a thing or two about the law and about how free debate works in a free country.”

As the case has played out, however, Lowry’s hubris has proven to be unwarranted …

Now, as the suit grinds onward, the Review faces fairly dismal prospects. The suit could eventually be dismissed, but that is looking less likely. What’s looking more likely is that Mann could win a substantial judgment in court or the magazine could settle out of court.

The Week doubts that the publication could financially survive either of those outcomes. In 2005, before his death, Buckley estimated that the Review had lost more than $25 million in its 50 years of operation. It has never enjoyed a single moment of robust financial health competing in the “free market of ideas,” but has relied on reader contributions and bailouts from wealthy donors for the entirety of its history.

Conservatives like to point Buckley’s legacy and the Review as the reasonable, moderate edge of an regressive, reactionary party. In its history, the magazine has consistently staked out far-right positions that favor whites over nonwhites and plutocrats over the middle and working classes.

Here is the warmed-over response from the so called business community by way of Bloomberg:

Climate-Change Skeptics Have a Right to Free Speech, TooStephen L. Carter

Of course we need defamation law. But our constitutional tradition correctly makes it difficult for public figures to prevail. Close cases should go to the critic, no matter how nasty or uninformed. The preservation of robust dissent allows no other result, and robust dissent is at the heart of what it means to be America.

I am old-fashioned enough to believe that the cure for bad speech is good speech. Yes, it’s a cliche. But it’s also a useful reminder. Nobody is forced to enter public debate. Once you’re there, it’s rough and tumble. Unfair attacks are as common as dew and sunshine, and everybody’s reputation takes a beating. That’s the price of freedom.

The central issue has little to do with the likely outcome — the bankruptcy of the worthless National Review.

Rather, there is the panic over the likelihood of carbon emitters and their shills being held to account. Right now, a jury aims to measure shills against their words: the shills don’t like it one bit. If the trial ends in settlement there will be other trials holding shills to account for their lies. If the emitters are lucky there will be trials holding emitters accountable for their actions.

If the emitters aren’t lucky: (finger cutting gesture across throat).

Because there are indeed consequences to carbon emissions and even the most stupid shill knows it.