Potential Black Swan events are myriad – ranging

from an attack on Iran to an overthrow of

the Saudi government to increased belligerence

from the new regime in Pyongyang, multiple

sovereign downgrades or an oil shock.

Coordinated recessions in the US and the Eurozone

can’t be ruled out and nor can a collapse

of the dollar, civil unrest in Russia or more geological

events such as those seen in Fukushima

last March…. in short, the list is long …

Grant Williams

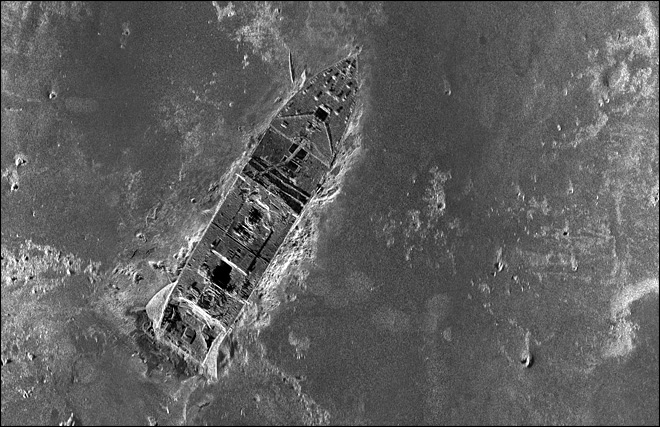

100 years ago today, one of history’s most (in)famous swans took flight: on April 10, 1912 the RMS Titanic departed White Star Line’s Southampton dock, toward Cherbourg then Queenstown, Ireland. A mere five days later the ship joined tens of thousands of other wrecks strewn across the bottom of the world’s oceans.

The gap between what an enterprise ‘earns’ (zero) and what it must pay for inputs becomes unbridgeable. That is, the cost of credit needed to make these enterprises ‘profitable’ is too high. This is why the world’s industrial economies are collapsing with nothing at all to be done to stop them.

Nobody could have seen it coming. The Titanic was unsinkable. It was commanded by the line’s most experienced Captain. The crossing between Ireland and New York was routine. There was no expectation of bad weather. The only issue was a coal-miners’ strike in England that did not allow the Titanic to take on as many passengers as she was designed to carry.

There were problems, of course, there always are. One thing leads to another, there is the cascading series of small failures that — by themselves — would not cause the swan to take a nose-dive, taken together were fatal. The entire Titanic enterprise was constructed upon a foundation of false- or not-quite-true assumptions. Captain Smith did not order the ship to slow as it approached the ice-field. Smith believed his ship to be unsinkable and assumed that any encounter between Titanic and ice would be of no consequence. The ship’s duty officer gave the incorrect order to reverse engines as the ship approached the iceberg. This rendered the ship unresponsive to the helm. He had only been on the ship for a few days and could not know how the ship would respond to orders from the bridge. He assumed the Titanic would maneuver the same as other, similar White Star ships.

The flight officer of Air France flight 447 performed an improper maneuver to correct the slight roll his aircraft after airspeed indicators caused the flight-control computer to switch itself off. The officer over-reacted to the changing attitude of the aircraft by inadvertently pulling the nose of the aircraft up. The outcome of his error — the consequence of icing pitot tubes — was a stall at high-altitude and the uncontrollable descent of the airplane.

The operators of the Three Mile Island Number Two nuclear power station did not realize that the pilot-operated relief valve PORV indicator was giving irrelevant information: that the primary circuit relieve valve solenoid was not energized. This was correct but it didn’t matter, the valve itself was stuck open. A gauge that indicated the temperature downstream of the valve was not visible and the operators were not trained to look for it. By the time the error was realized — by a new shift of control room operators hours later — most of the cooling water in the reactor pressure vessel had been blown through the open valve onto the floor of the reactor containment by steam pressure. The outcome was the release of radiation into the environment and the loss of a multi-billion dollar reactor.

– An incestuous financial and regulatory relationship between the reactor operator Tepco and the Japanese government,

– A fundamentally unsafe reactor design,

– Cheaply built reactors too near the sea level so as to save relatively small amounts of money,

– Crews made up largely of poorly trained, poorly paid ‘contract’ workers often press-ganged into reactor service by Japanese Yakuza gangsters,

– No operating manual on site, no rigorous emergency training for critical staff,

– Inadequate safety equipment: missing or non-existent dosimeters, hazmat suits, respirators, even flashlights at site,

– Insufficient battery backup for emergency cooling systems,

– staff who ‘forgot’ spent fuel pool in reactor building number four, who ‘forgot’ 10,000+ tons of lightly radioactive water in waste-handling building that could have been used to cool the reactors rather than seawater,

– Unclear chain of command and confusion over roles immediately after the earthquake,

– Inoperable reactor vents which resulted in no cooling for reactor cores for extended periods (and probably resulted in steam pressure pushing water out of the cores). The result of these little failures — add a massive earthquake and tsunami — is the ongoing calamity at Fukushima.

Finance failure is little different from others: there is a chain of false assumptions that, by themselves are insignificant, but together lead to disaster. One assumption is that credit and business have a tendency toward expansion. This is silly because thermodynamics insists otherwise. Our strategy to overcome natural physical laws in 2012 is for central banks to recycle credit and pray.

The central banks are the last line of defense for finance’s Titanic. Water leaks in faster so the bankers can bail. The strategy is to keep bailing, to keep lending more and more credit, which is what the ship does not need. Every bucket bailed by the bankers winds up somewhere else inside the ship.

Put a dirty car through the car wash what comes out the business end isn’t a new car, it’s the same old jalopy with the dirt scrubbed off. Meanwhile, every trip through the wash adds the cost of a new car to the bill that must be paid sometime in the future. The harmless assumption is that the washing process will end soon and that the bill will be paid by magic as it has always been paid in the past. That there will be a general increase in the amount of available credit on private debt markets.

A tiny problem is that industrial enterprise does not pay for itself. Except for taxi drivers and deliverymen, driving a car and all the trillions invested in the ‘experience’ around the world does not produce a return. It is pure waste for its own sake that must be propped up with bottomless debt- and energy subsidies. This is the reason for the tens- of trillions of dollars worth of debt taken on in the first place. If industry could pay for itself it would have! There would be no debt because returns earned by industry would have retired it!

The outcome of subsidized waste over the term of decades is repricing of inputs due to decreasing rate of supply relative to the scalding increase in demand. The gap between what an enterprise ‘earns’ (zero) and what it must pay for inputs becomes unbridgeable. That is, the cost of credit needed to make these enterprises ‘profitable’ is too high. This is why the world’s industrial economies are collapsing with nothing at all to be done to stop them.

Central banks provide credit against collateral. Their efforts fail because of the waste-based economic system that falsely labels non-remunerative activities as ‘production’.

Since industrial enterprises cannot pay their own way there is no relevance to central banks’ strategy. Because industry cannot earn, all industrial collateral is worthless.

Central bankers swap impaired assets for ‘new’ assets, the swapped assets are buried on the central banks’ balance sheets. The impairment has been temporarily shifted from one account to another, not eliminated. The expansion of the central bankers’ balance sheets accompanies the shrinkage of private sheets elsewhere. Meanwhile, more finance assets become impaired because the central bank swaps do not represent either new business or new credit, only buckets of liquidity sloshed from one part of the Titanic to another.

A problem is the slowdown in the expansion of private credit, much of which is unsecured. What is called a ‘boom’ is an expansion of un-collateralized or under-collateralized credit. This includes credit cards, student loans, HELOCs and poorly/fraudulently underwritten mortgage/business loans as well as loans within (shadow) banking secured against phantom/re-hypothecated collateral. There is no business activity that provides a return except for Hyman Minsky’s Ponzi finance schemes. Loans must be retired with new loans. Meanwhile, collateral worth shrinks across the board.

Central banks are collateral constrained, that is the nature of central banking. A bank making unsecured loans cannot be the central bank. Otherwise, collateral would be of indeterminable worth: all banking would eventually cease because there would be no unambiguously worthwhile collateral or ‘risk-free assets’.

The purpose of the central bank is to defend the worth of collateral. It takes onto its own balance sheet collateral that the market refuses. By doing so it insures there is always a bid for it in the marketplace. This is a form of institutionalized moral hazard: because the central bank takes on collateral at par the other banks are given the incentive to do the same. Banks become secure enough in the quality of the collateral offered … to lend against it, at least that is the desire.

There are two basic money systems in this world: the debt money system and fiat money. The term ‘money’ includes both currency and credit. Both systems are binary: the debt system binary is ‘asset = liability’, the fiat binary is ‘issue = tax’.

In the debt-money system the central banks don’t ‘print money’: currency increases as government securities are exchanged for at-par loans from the bank. The loan from the bank becomes currency in the hands of the government. In a fiat money system the government issues currency without offering security or borrowing. Because the government is the issuer, security is presumed: consider Abraham Lincoln and the ‘Greenbackers’. Unfortunately, governments choose not to issue fiat currencies. Otherwise the massive overhang of dead-money debt could be swiftly reduced, there would be no generalized increase in the money supply (inflation) as applying currency to existing debt would extinguish both.

Dead-money liabilities that exist on ledgers are phantoms: taken on as collateral they do not exist in any meaningful form. Companies borrow trillions to buy hydrocarbons. Where are these hydrocarbons so that they might be repossessed by the lenders? In the atmosphere in the form of CO2 and nitrous oxides. Let the bankers repossess these gases. More accurate liability is the damage CO2 does to the atmosphere and the life support system, let the bankers possess these liabilities as well.

Any banker stupid enough to make pointless and destructive loans is well deserving of ruin and much worse.

The bankers would see this as a form of repudiation as it indeed would be. Issued currency would be no different from the loans themselves, created with a push of a button on a keyboard: printed money for printed loans! It is the force of the lenders’ habitual oppression combined with reflexive cowardice on the part of governments that sanctifies the bankers and their ‘money’ over everything else.

Here is more from Modern Monetary Theory and Philip Pilkington:

MMTers make the claim – following in the footsteps of Abba Lerner – that the government budget should not be subject to any sort of arbitrary balancing constraint. Instead Lerner and the MMTers advocate that the government budget balance should be conceived of strictly from the point-of-view of real economic variables. Thus, if there is unemployment the budget should be unbalanced, while if there is high inflation due to output capacity being outpaced by demand the budget should be moved closer to balance or even, in certain cases, into surplus. Lerner referred to this approach as ‘functional finance’.The reason that both Lerner and the MMTers feel confident in making this case is because they hold that a government that issues its own currency and allows their exchange rate to float is not subject to any budgetary constraints. They can essentially issue new money – together with government bonds, if they so wish – until they begin to see inflation. Inflation, then, is the only real constraint to a government that issues its own currency and maintains a floating exchange rate.

If the government issues currency, why would it issue new bonds? To provide a risk-free asset that can ‘finance’ activities (healthcare and pensions) that would be otherwise costly to fund directly. The economy would escape the ZIRP trap: the central bank would have no need to defend ultra-low interest rates as the demand for near-money would keep excess currency from entering the economy.

However, if a developing country tries to spend up to the point of full employment while maintaining a floating exchange rate they are, as stated above, likely to see devaluation and inflation take place as the weakened currency chases more and more imported goods that the country’s own domestic industry cannot produce.

Agreed …

As incomes rise through government spending programs (and potential rises in real wages) people will be more inclined to seek out goods and services that were previously thought of as only available to a small stratum of the population. Devaluation and inflation are then almost inevitable.

Subsidizing waste as resources shrink is bankruptcy in a can. Analysts are stuck with the assumption of credit-stifled demand for consumer goods such as cars and tract houses. The problem is insufficient supply of the inputs needed to run that demand.

When the market-driven price for energy inputs decline it is because demand has been bankrupted somewhere within the system. In the ‘good old days’ of the early oughts, the demand was local, now the destroyed demand is entire countries, swept away in the matter of weeks.

The high-priced crude strands economies and trillions of (borrowed) ‘investments’ that were made assuming $20 crude in perpetuity. The higher the crude price is over $20, the longer this price holds, the more destructive the outcome is.

At the same time, a price low enough to allow increased demand on the waste side is too low to bring new oil to the marketplace.

But think about this for a moment; if we adhere to a purely functional view of finance then we have far more options available than might appear at first glance. We can actually use government fiscal policy to guide domestic investment decisions and ensure that the goods and services people desire as their incomes rise are produced at home rather than abroad.

There is but a slim chance to use finance to move away from consumption/waste and to restructure. The race is on between ourselves and the efficiency of our machines now set on ‘swan dive’.